Since 1968, when Bullitt first shot into theaters turning Steve McQueen and his Ford Mustang Fastback into global icons, the “police procedural” has been a staple of crime stories on screens big and small. Bullitt’s smashing success, both commercially and artistically, ushered in the first “Golden Age” of the police procedural. The genre’s mainstream popularity has ebbed and flowed since those heady days, but for crime aficionados, it has never faded. Towards the end of the ‘Aughts, the procedural was disappearing from the big screen, as Hollywood became increasingly preoccupied with cartoon super-heroes. Movie studios had little interest in the gritty social realism and visceral excitement that a great cop story provides.

HBO resurrected the genre. When the first season of The Wire debuted on HBO in 2002, the minds of police procedural fans everywhere were blown. The Wire was every bit as compelling, and every bit as badass, as Bullitt. But it felt completely new. Thanks to the long-form television series, the police procedural is experiencing a second “Golden Age.”

Over the past five decades, the genre has evolved with the times. But certain core elements have remained constant. We watch police procedurals to get up close and personal with detectives at work. What we see is not always—not even often—pretty. But we can’t stop watching. The detectives at the heart of the best procedurals believe that the they are the last best hope for justice in a compromised world and they won’t stop until they take its full measure. No matter what the cost.

Limiting any list to twelve selections means overlooking other worthy entries, but these twelve takes are all solid gold. Twelve stories that take us deep behind the badge, that ooze with blood, sweat and tears, and that feature heroes with the sort of obsession that borders on a clinical disorder. What does that say about us? Why do we keep coming back to share time with these borderline personalities and their obsessions with building cases, catching killers and driving cars dangerously fast?

Here are twelve chances to try to sneak a look behind the hard eyes of these detectives and get a glimpse at what makes them really tick. But you better look fast; don’t let them catch you staring.

Bullitt (1968)

“There are bad cops and there are good cops and then there’s Bullitt,” read the movie’s tagline. That idea—that one tough cop could bring evil men (and women) to justice—became the staple for the genre for years to come. 1968’s box-office smash stars Steve McQueen as San Francisco Police Lieutenant Frank Bullitt. The film was directed by Peter Yates and produced by the criminally under-appreciated Phillip D’Antoni. Bullitt presented a new kind of hero, a brooding, existential police detective hero wearing a sport coat and shoulder holster. The film even received an Academy Award for film editing, a nod to the iconic car chase at the center of the film. Listen for Lalo Schifren’s jazzy score and watch for a cameo appearance by Robert Duvall as a cab driver. And that shoulder holster? Steve McQueen’s research for the part included riding alongside Dave Toschi, SFPD’s top homicide detective. McQueen borrowed more from Toschi than his experience; he asked wardrobe to supply him with the same sportcoats and shoulder holster worn by Toschi. This is not the last we will see of Dave Toschi or his shoulder holster.

The French Connection (1971)

Another blockbuster from producer Phillip D’Antoni, this one directed by William Friedkin and starring Gene Hackman as Detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle. Hackman shares the screen with Roy Scheider as his partner, Buddy Russo, and with a dirty brown Pontiac Le Mans that he drives with reckless abandon under New York’s elevated train in the film’s signature car chase. This 1971 film is the high-water mark of the first Golden Age. The film not only finished second at the box-office (behind Fiddler of the Roof) it also dominated the 1972 Academy Award ceremony, winning five awards including Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Picture. If life was fair, then the Academy would also have presented a special award to Hackman’s Pontiac Le Mans.

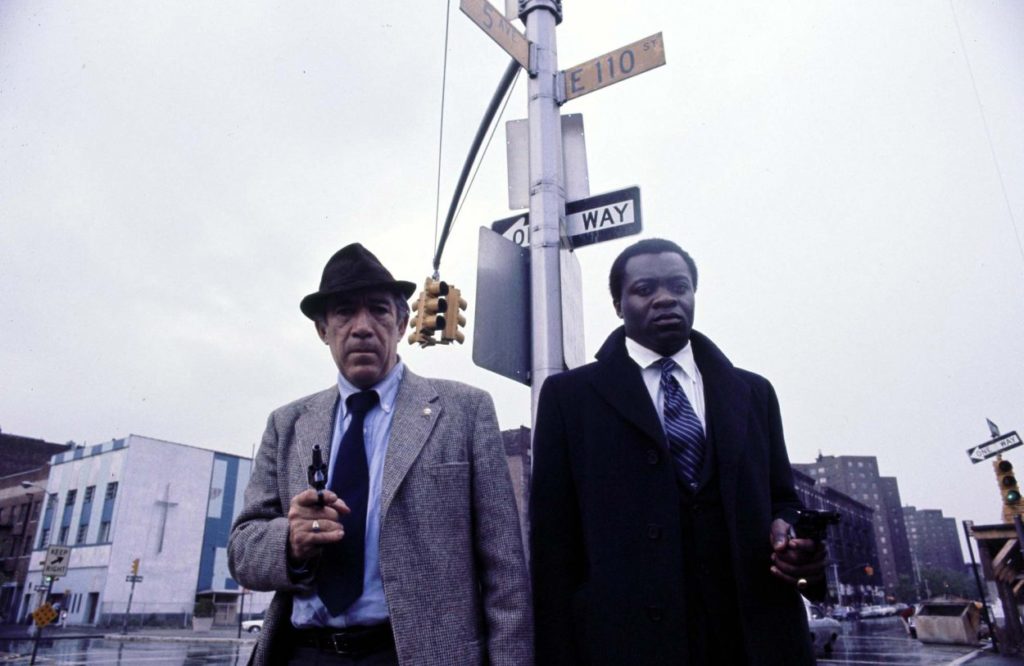

Across 110th Street (1972)

This 1972 gem typically gets lumped in with the “blaxploitation” era, but for me it feels closer to the gritty, finely wrought noir of films like The Friends of Eddie Coyle, another great crime caper film from the early 1970s. Across features a fine cast lead by two well-paired tough-guy actors, Anthony Quinn and the incomparable Yaphet Kotto. For my taste, this film comes closer to the look and feel of Chester Himes’s splendid Harlem Detective Series than any film actually drawn from Himes’s work. Bobby Womack’s excellent soundtrack, including the signature title track, adds another dimension of meaning to the film. Give this film a spin because, as Bobby Womack sings, “Across 110th Street is a hell of a tester.”

The Seven-Ups (1973)

Phillip D’Antoni both produced and directed the last of his trilogy of great procedurals. Roy Scheider is the star this time around, playing Detective Sonny Grosso and leading an ensemble cast that includes Bill Hickman, the legendary stunt coordinator who choreographed the car chases in Bullitt, and The French Connection. Hickman gets one last chance in this 1973 film and he used it to produce the mother of all car chases. Another battered Pontiac? Make that two Pontiacs. Locked in a ferocious 10-minute chase. These D’Antoni/Hickman car chases are thrilling set-pieces, but they are much more than that; each chase dramatizes the internal “drives” of the lead characters. Frank Bullitt, Popeye Doyle and Sonny Grosso will stop at nothing to solve their cases. They drive their cars like they drive themselves. To the limit. The three D’Antoni cop films both pioneered and defined the genre. They are not to be missed and reward repeated viewings.

Serpico (1973)

Sidney Lumet’s Serpico, released in 1973, is much more than a police procedural; it is also a story of a crooked city, an honest cop, and the corruption that eats away at the at fabric of the justice system. But it makes my list for two reasons. First, the movie is a procedural; it takes us inside Frank Serpico’s real-life crusade to clean up the NYPD. Second, I want to draw attention to a largely forgotten masterwork by a director and star at the height their powers. Why do we call the early 1970s “the golden age” for crime films? Because in those golden years, mature, multi-layered films like Serpico seemed to be almost routine. Imagine that today. I will save you the headache. Hollywood could not or would not green light Serpico today. Perhaps HBO or AMC would.

The Laughing Policeman (1973)

Is Walter Matthau the most under-appreciated star of crime movies? The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Charley Varnick and this film make that case. This 1973 nugget is hard to find but worth the effort. Matthau and Bruce Dern play a mis-matched pair of cops, working together, and sometimes at odds, to solve a city bus massacre that killed seven civilians and one cop. In pursuit of the killer, they are assisted by a young, and quietly dangerous, Lou Gosset Jr, and the always excellent Anthony Zerbe. The screenplay is loosely drawn from a Swedish crime novel, but relocated to San Francisco at its grimy early 1970s nadir. Matthau plays it straight throughout and Bruce Dern’s mustache is worthy of its own special effects category.

Le Petit Lieutenant (2005)

The procedural genre knows no borders; it is not confined to the United States and its heroes need not be male. Exhibit A for that proposition is Le Petit Lieutenant a 2005 French police drama set in streets of Paris starring the superb Nathalie Baye. If you don’t know Baye, who plays Commandant Caroline Vaudieu, then this is a very good place to start your studies. Baye is the leader of a team of plainclothes cops, including the title character, a “young lieutenant” whom she takes under her wing. The actress won a slew of well-deserved European film awards for her portrayal of a recovering alcoholic who discovers that the best substitute for her addiction to alcohol is an obsession with case work and catching criminals. If you like Baye’s style, then look for her as an alluring police informant in one of her earliest roles, the excellent 1982 French crime drama, La Balance.

Zodiac (2007)

Is Zodiac David Fincher’s best film? Is it the best film of 2007? Is it the finest police procedural ever made? Is it the most unappreciated film of the past 20 years? For me, the answer to all those questions is yes. Zodiac, above all other police procedurals, animates the exquisite tension between the thrill of solving a crime—in this case the identity of the Zodiac Killer—and the frustration of not being able to prove the case in court. Jake Gyllenhaal may not be a cop but make no mistake, his character, Robert Graysmith, is a detective. Gyllenhaal shares the lead with Mark Ruffalo portraying—wait for it—Detective Dave Toschi. That’s right, the same detective Steve McQueen relied on to model Frank Bullitt. Toschi was a lead investigator on the actual Zodiac investigation and an advisor on the film. Mark Ruffalo studied Toschi to get his mannerisms just right. Including the legendary shoulder-holster. Fincher made a deep dive into the actual case files and his homework shows in every frame. I watch this film once a year to be reminded of what it takes to build a case that can stand the ultimate test, that of proof “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Watch and judge for yourself. Just don’t go down into the basement.

(As an aside, Clint Eastwood also drew on Dave Toschi for his portrayal of Police Inspector Harry Callahan in 1971’s Dirty Harry. Don Siegel’s 1971 film about Callahan’s pursuit of a serial killer modeled after the Zodiac was released while Toschi’s own investigation was still in full swing. The film reportedly upset Toschi, who did not care for Dirty Harry’s methods of administering street justice. In a scene dramatized in Fincher’s film, Toschi, in distress, storms out of an early screening of Dirty Harry. Mark Ruffalo, in an in an interview with the website Collider, said that Toschi “couldn’t take [Dirty Harry] . . .It was so simplified.” Street Justice usually is.)

American Gangster (2007)

If Zodiac was not the best film of 2007, then maybe it was this film, directed by Ridley Scott and featuring not one, but two, fully realized performances from its stars, Denzel Washington and Russell Crowe. Washington got all of the attention, and the awards, and that makes sense, his Frank Lucas is the flashier role, a genuine star turn. Crowe’s Detective Richie Roberts is something else entirely. Crowe loses himself in the role and creates one of the most honest portrayals of a police detective at work that I have seen. If you have not watched this film recently, then I suggest another screening just to see Crowe. He captures the essence of the working cop. Every gesture, every word, is just right. Crowe’s Roberts may not drive dangerously fast but he is a throwback to the D’Antoni films. Detective Roberts is a steamroller and he will—no matter how long it takes—get his man.

The Wire Season One (2002)

From the moment the needle drops on the Five Blind Boys of Alabama’s version of “Way Down in the Hole” playing behind the opening credits of Episode 1, until the final fade-out on Omar (and his hand cannon) in Episode 13, David Simon’s long-form masterwork, The Wire, had me hooked. For me, these first 13 chapters of The Wire share with Zodiac the “best in show” prize for police procedurals. The Wire would hit other heights in seasons to come, especially with Season 4, a sustained dramatic success, but Season 1 is the procedural. McNulty, Bunk, Barksdale, Omar, Bubbles, the corner kids and the couch kids, the street cops and the police brass. Every note was pitch perfect. Is this fiction or is it fact? Or is it something in between. Police shows would never be the same after the kaleidoscopic display of character and plot in The Wire. Some complained—and still complain—that this show is “too depressing.” I could not disagree more. For me, Omar, the stick up artist, summed it up with a crooked smile at the end of Season 1: “It’s all in the game.” Don’t condemn the player. Condemn the game. David Simon manages to do just that.

The Fall Season One (2013)

The Fall, a 2013 British-Irish television series set in Northern Ireland stars Gillian Anderson as Detective Superintendent Stella Gibson. Allan Cubitt, a graduate from Prime Suspect (a series I invite you to dip into) wrote and produced. Season One focused on Detective Superintendent Gibson’s entrance on the scene to provide a fresh set of eyes to review “open case file” that suggests a serial killer is at getting away with murder. Anderson is most certainly obsessed with her suspect. That is something of an understatement, and The Fall takes her investigator’s obsession in a new direction. Subsequent seasons lost the thread, exploring the killer’s psyche rather than the detective’s work, but Season One was a genuine corker. Put it in your queue and prepare for a binge.

True Detective Season One (2014)

Writer Nic Pizzolatto and director Cary Fukunaga caught fire in 2014 with the debut season of True Detective, a dark riff on the “buddy cop” movie. Pizzolatto immersed himself in police manuals while creating his homicide detectives, Woody Harrelson’s Martin Hart and Matthew McConaughey’s Rustin Cohle. The homework paid off; Hart, Cohle and all the shields around the station house are every bit as real as those in The Wire. Sure, the dialog can be overripe, but Fukunaga’s camerawork and the surefooted acting keep Season 1 on the rails. Of course, another serial killer is on the loose. This time it’s 1995 in the bayous and lowlands of Louisiana. McConaughey and Harrelson catch the case but their obsession with catching the killer carries them across three decades, one broken marriage, one epic fistfight and countless cans of Lone Star beer. These two cops may be “buddies” but they are not exactly friends. McConaughey’s Rust Cohle is especially charismatic, particularly in an interrogation room. If ever a character deserved a sequel, or a prequel, it’s Rust Cohle. Alas, that was not to be. The second season of True Detective abandoned Fukunaga and all of Season One’s characters. Whatever Season 2 was, and I am still not sure, I know it was not a procedural. Pay Season 2 no mind. If you want to see police work operating at the very margins of the law, and sometimes well outside those margins, then tune into Season 1 and get out your notebook.

***

That makes twelve. My shift is over and I am Code 10-42, signing off. A new generation of writers and directors are leading the evolution of the police procedural. Let’s see where they take us in the next decade— or five.