When the world’s greatest scientist visited Los Angeles in January 1931, he was asked if there was anyone he would like to meet. He named the biggest movie star in Hollywood.

A few days later, Albert Einstein and Charlie Chaplin, attired in black tie, their spirits buoyant, stepped out of a limousine. The Tramp had invited the Genius to be his guest at the premiere of “City Lights,” a heartwarming masterpiece of compassion and empathy. It was the beginning of an enduring friendship.

I knew none of this two decades ago when I stumbled across a photo of the two icons in the theater’s lobby that fateful night. In the 1930’s, Chaplin was the most famous entertainment figure in the world, a Hollywood mogul who wrote, directed, produced, and starred in his films. Einstein, a Nobel prize winner, was the most celebrated—and recognizable—scientist in the world. But what connected these two luminaries? A little research uncovered the answer.

Enter Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels.

Einstein was an outspoken critic of militarism and authoritarianism in Germany where his theories of relativity were derided as “Jewish science.” He fled the country of his birth in 1933 after Hitler seized power.

Even before Chaplin made “The Great Dictator” in 1940, lampooning Hitler, Nazi propaganda chief Goebbels had labeled the actor a “little Jewish acrobat, as disgusting as he is tedious.” In fact, Chaplin was not Jewish. He was, however, vocal in his anti-fascist views. When Einstein fled Germany in 1933, he was declared an enemy of the state. The Reich burned his books, seized his bank accounts, and published his photograph in a newspaper with the caption, “Bis Jetzt Ungehäengt.” Not yet hanged.

The growing atrocities in 1930’s Germany were familiar to me. What I didn’t know, and what has largely been forgotten, was that fascists were on the march in the United States.

Enter Professor Ross.

In 2017, Steven J. Ross, a history professor at the University of Southern California, published “Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America.” It was a non-fiction tale of Nazis, armed and dangerous, in California in the 1930’s.

Who knew? Not me.

Greater Los Angeles was a hotbed of fascist activity. The German American Bund organized marches, ran summer camps modeled after Hitler Youth, and held picnics to honor the Führer’s birthday. In downtown Los Angeles, the Aryan Bookstore peddled Nazi propaganda.

William Dudley Pelley, a screenwriter who had penned several Hollywood motion pictures, founded the Silver Legion of America, a paramilitary militia intent on overthrowing the U.S. government.

Professor Ross writes: “Plans existed for hanging twenty Hollywood actors and power figures, including Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Charlie Chaplin, Louis B. Mayer, and Samuel Goldwyn; for driving through Boyle Heights and machine-gunning as many Jewish residents as possible; for fumigating Jewish homes with cyanide; and for blowing up defense installations and seizing munitions from National Guard armories on the day the Nazis planned to launch their American putsch.”

Who would stop these homegrown terrorists? J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI was too distracted chasing suspected communists to worry about fascists. The LAPD, led by its thoroughly corrupt Chief, James (“Two-Gun”) Davis, was preoccupied with illegally turning back Dust Bowl refugees at the state border in his notorious “Bum Blockade.”

In real life, Leon L. Lewis, a courageous Los Angeles lawyer, hatched an undercover operation that helped infiltrate and expose the violent fascist groups. But I write fiction. So…inspired by those true events, I had the core of a tale of historical fiction: Einstein and Chaplin vs. Nazis in 1930’s Hollywood.

But how could our heroes, no matter how brilliant and talented, credibly combat this peril?

Enter Sergeant Georgia Ann Robinson.

The first Black female officer in LAPD history, Robinson founded women’s shelters, worked with the NAACP, and fought to integrate schools. So my narrative would feature three outsiders—the legendary actor, the brilliant scientist, and the trailblazing female cop—banding together to fight the fascists in the City of Angels. Now that’s a story.

But the research!

Writing nearly two dozen contemporary legal thrillers legal did not prepare me for historical fiction. Every page demanded painstaking accuracy. How did people dress? What cigarettes did they smoke? What cars did they drive? What were the most popular dishes at Musso and Frank, and what were the stops on the Red Car line from Hollywood to downtown L.A.?

Even more daunting, I had to realistically portray—in action and dialogue—a casting call of historical characters. In addition to Einstein, Chaplin, and Sgt. Robinson, key roles are played by Charles Lindbergh, Joseph and Magda Goebbels, Douglas Fairbanks, German consul Georg Gyssling, and American fascist William Dudley Pelley.

I grossly underestimated the research required to build a world populated by historical figures. My home office was soon littered with towers of books, my file cabinets bulging with Internet discoveries. As much as possible, the dialogue tracks what the characters actually said and wrote. That includes the epigraph, which establishes the theme of the novel:

“The world is a dangerous place, not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.” —Albert Einstein

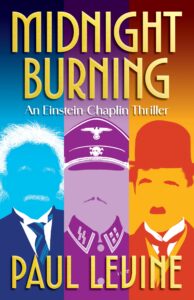

“Midnight Burning” is the most challenging book I’ve ever written, but also the most rewarding. Through the partnership of Einstein, Chaplin, and Sergeant Robinson, I found myself telling a story that resonates eerily with our own time—a reminder that the battle between tyranny and freedom never truly ends.

***