One hears it all the time. A reader praises a book because they find the characters “likable” or “relatable.” Another reader dismisses a book because they couldn’t “identify with the characters” or, more damningly, “didn’t care about the characters.”

Why do some characters inspire empathy in some readers while leaving others cold? By what alchemy do writers “make people care”? Should “caring” even matter? These are ancient literary mysteries, of course. But for a crime writer working in the 21st century, a time of snap judgments and short attention spans, trying to get readers to connect with characters who are difficult, morally ambiguous, or who do terrible things, can present unique challenges.

Based on my unscientific observation, I would say there are four principal ways in which readers today experience their gut reactions to literary characters. To be brutally reductive about it, these are the four corners of subjectivity:

Likability. This can be broken down to that dictum of political consultants: that voters prefer someone they would enjoy going out for a beer with.

Identification. On the most basic level, does a character share aspects of a reader’s socio-cultural background? Do they “look like you”?

Relatability. A character might not look like you, might not be someone you’d want to have a beer with, but maybe they’re going through grief over the loss of a loved one. If you’ve known such grief yourself, you might be able to relate to them, at least on this situational level.

Caring. In other words, giving a damn about what happens to a character. Ideally, the reader is so invested in following the main character’s path and learning their destiny, that they fully engage with a novel, whatever the flaws or vices of the protagonist.

I often enjoy stories of Good Guys vs. Bad Guys. (And, please note, I use “Guys” in the gender-neutral sense here.) But the anti-hero has been with us for a very long time, going back at least as far as Shakespeare’s Richard III. When it comes to fiction in general and crime fiction in particular, I’ve always been drawn to the darker, more morally complex protagonists.

It’s almost automatic to “care about” a main character who is a police officer. No matter what their interesting personal failings, cops are ostensibly there to keep folks safe from harm. Crime literature of the past half-century is filled with troubled, traumatized cops, from small town USA to the farther reaches of Scandinavia. And, often enough, the criminals they are up against have committed such vile atrocities that it’s impossible not to root for the cop, whatever their flaws. The same goes for FBI and CIA agents, forensic criminologists and lawyers, so long as their motives are sound. Their role is to solve crimes, pursue justice, restore order. What’s not to like?

The anti-heroes I first loved weren’t cops. They were private detectives: Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. They weren’t government employees. They were jaded loners, far too cynical to expect they would ever impose order on a world that was inherently corrupt. They didn’t always follow society’s codes of honor, because they occupied a moral zone of their own, rejecting both the official power structure and the criminal class.

Then along came The Godfather by Mario Puzo. Published in 1969, the novel broke new ground by transforming a classic villain of crime fiction, the mob boss, into a compelling protagonist. Don Vito Corleone is shrewd, wise and ferociously devoted to his family. Through corruption, he thrives in a corrupt universe. And in the end, Puzo depicts him in an almost beatific way. In the novel, Don Corleone’s last words, as he dies in his tomato garden, are: “Life is so beautiful.”

If Puzo’s bestselling novel was a crime fiction breakthrough, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 film adaptation was a cultural phenomenon whose influence endures today. In addition to Marlon Brando’s charismatic incarnation of the Don, the sublime supporting cast, and the director’s mastery of his art, the film captured the Zeitgeist perfectly. The idealism of America in the 1960s had been poisoned by a bloodbath of political assassinations, social unrest, a grinding war. The Godfather was the Number One film at the box office the week of the Watergate burglary. Don Corleone was the ultimate anti-hero of his time.

It was television, at the turn of the 21st century, that nurtured the evolution of the criminal anti-hero. It’s hard to convey to a young viewer today just how shocking it was to see the lead character in a series, even if he was a New Jersey crime boss, garrote someone in a most intimate way, in Episode 5 of Season 1 of The Sopranos, which first aired in 1999. David Chase’s monumental creation, Tony Soprano, is even obsessed with The Godfather, the film trilogy, at least.

Tony Soprano spawned a generation of anti-heroes on the small screen. TV and streaming are now full of likable serial killers, relatable cannibals, hit men you might identify with on one level or more. A great many viewers care about them.

Books are different. Words on a page get into your head differently. When you’re reading a novel, your consciousness is intertwined with someone else’s on an intimate level. That, in fact, is the power of the written word. That’s why, after all these centuries, people still want to burn or ban books.

When it comes to bringing psychopathology to spellbinding life on the page, Patricia Highsmith was an absolute master. She and her supreme anti-hero, Tom Ripley, warrant an entire essay all to themselves: see Edmund White’s brilliant piece in the New York Times, March 24, 2021.

One of the most intense reading experiences I’ve ever had was with Donald E. Westlake’s The Ax. Published in 1997, I read it, for the first time, in 2008. The protagonist, Burke Devore, gets the ax from his mid-level executive job, in middle age, with a house and cars and two kids to put through college. Desperate, unemployed, Burke decides to literally kill off the competition for a coveted job at a paper mill.

I did not like Burke, found him to be a cold fish. I didn’t identify with this white suburban dad and his corporate way of life. And while I could relate to his economic insecurity, I could definitely not relate to his reaction to it. But, thanks to the enthralling voice Westlake gave him, I cared enormously about Burke Devore as a twisted piece of humanity. I cared so much that, even as his methodical murders became more grotesque and intimate, I was actually rooting for him to get the job, by any means necessary.

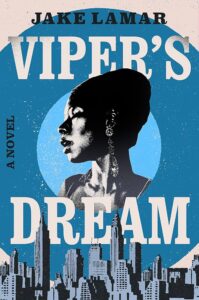

My new book, Viper’s Dream, is a hard-boiled crime novel set in the jazz world of Harlem between 1936 and 1961. The anti-hero is Clyde “The Viper” Morton, one of the most powerful, respected and feared Black gangsters in America.

In France and in Britain, Viper’s Dream has had enthusiastic reactions from readers. But whether they like or identify with Viper Morton, relate to him or care about him, or not, people sometimes ask me in what ways I resemble my anti-hero. He is, after all, a gangster, a drug dealer, a murderer. My simple answer to the question is: We’re both allergic to cats.