The 1980s were a tough time to be a kid in Ireland.

Globally, the prospect of nuclear war hung over my childhood like a toxic cloud. The arms race between the USA and the USSR held a threat beyond imagining. Jimmy Murakami even made a beautiful animated film about the end of the world called When the Wind Blows in which all of its cutesy and charming characters died from radiation poisoning and despair after a nuclear attack. John Lennon was shot dead on a New York City street. The Pope and President Ronald Reagan survived assassination attempts.

At home in Ireland too, there were also sinister things going on.

At home in Ireland too, there were also sinister things going on.In 1981, Malcolm MacArthur, a man with an aristocratic background, bludgeoned to death a young nurse who was sunbathing in a park, stole her car and later shot dead a farmer with his own gun. While the manhunt was going on for the killer, MacArthur attended football matches and chatted casually to the Irish Police Commissioner and the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) about how the investigation was going. When he was eventually caught, he was found hiding out in the home of the Attorney General who was away on holidays at the time. The scandal rocked the establishment to its core.

My parents knew people who had met MacArthur and they were incredulous that an upper-class man who moved in such high circles could have been involved in two murders.

And there were other things happening in Ireland that were not discussed at the dinner table. In January 1984, a fifteen-year-old girl, Ann Lovett, left school as normal and went to a holy grotto in the grounds of a church at the top of the town of Granard, where she gave birth alone on a dark and freezing afternoon. Without any assistance, there were complications and the baby died. She and her already dead child were discovered by other school children. By the time an ambulance arrived, it was too late and Ann also died. The entire community including her parents and the nuns who had been her teachers denied any knowledge of the pregnancy. It seemed that this little girl felt there was nobody who would help her, nobody to whom she could turn.

This story did not hit the headlines until a week after it happened. The townspeople closed ranks and refused to talk to the press. They wanted the story to go away, but the media would not let it go and radio programs were suddenly inundated with confessional letters from women who had had secret teenage pregnancies, women who had been forced to give up their babies for adoption, women who had committed the crime of getting pregnant outside of marriage, as if the babies had all been conceived miraculously but far from immaculately. Immaculate conception in the all-powerful Catholic faith was reserved only for the Virgin Mary.

The fathers of these babies were never held accountable. We had been taught that Eve had tempted Adam. Adam was never to blame.These girls, on the other hand, were considered sluts who had let themselves and their families down. It was believed that they must be punished and pay for their sins. They worked in convent laundries to earn their keep, hidden away until they gave birth. The young mothers were often incarcerated until they agreed to sign the adoption papers. Their babies were then adopted or sold abroad. The girls and women were told they were dirty, unworthy, and that God would never forgive them for their sins. The fathers of these babies were never held accountable. We had been taught that Eve had tempted Adam. Adam was never to blame.

A few months after Ann Lovett and her baby’s tragic deaths, Ann’s sister committed suicide. At my tender age, a teenage suicide was as incomprehensible to me as a teenage pregnancy. I read the headlines on my mother’s newspaper and I heard the matter discussed at length on the radio, but this topic, unusually, was not discussed at home. Not in front of me, anyway. It was too shameful to speak of, even in our liberal home. Women’s sexuality was not something to be contemplated. Even though Ann Lovett was below the age of consent, none of the reports ever used the word rape. This was an era in which divorce, homosexual acts, contraception and abortion were illegal.

In April of the same year, a newborn baby was found dead and abandoned on a County Kerry beach. It was known locally that 25-year-old Joanne Hayes had been pregnant by a local married man, Jeremiah Locke.

In fact, Joanne had already delivered her child, stillborn, and had buried it on the family farm. The shame of her situation had prevented her from going to a doctor or a priest.

Ignoring her version of events, the police charged her with the murder of the beach baby. They extracted ‘confessions’ from her family members stating that she had stabbed her baby with a knitting needle and that they had thrown the body off a cliff. A couple of days after she had been charged, Joanne’s baby’s body was discovered on the farm exactly where Joanne had claimed it was. Despite blood tests proving that Joanne and Jeremiah could not have been the parents of the beach baby, the police insisted that Joanne must have had sex with two different men within 48 hours, bore twins and murdered both babies. The Director of Public Prosecutions refused to proceed with the case and a Judicial Inquiry began into the police handling of the case.

Joanne was forced to give evidence at this tribunal which lasted 82 days and was asked the most deeply personal questions about her sexual history, her menstrual cycle and losing her virginity. It seemed that even though she was not at this stage charged with any crime, she was still on trial as the police robustly defended themselves. Joanne Hayes was questioned by 43 people: lawyers, doctors, psychiatrists and police. Not one of them was a woman. The judge concluded that the Hayes family had “freely” given false confessions to the police (despite the fact that all four of them came up with the same false story in four separate interview rooms) though he did concede that the investigation was “slipshod.”

All of these cases caused a sea-change and a rise in the force of women’s movements.All of these cases caused a sea-change and a rise in the force of women’s movements. Women began to organize and petition for the rights that every other progressive country enjoyed. Contraception was finally legalized in 1985. Homosexuality was legalized in 1993. Divorce wasn’t legalized until 1996. Finally, this year 2018, a referendum was held on legalizing abortion on May 25th. The referendum was upheld by a landslide majority and legislation should be in place by the end of the year.

The 1980s was a gothic horror decade of hypocrisy. The country was in deep recession. Unemployment was high. Women could do no right. Unmarried mothers were a drain on the state. Women who traveled abroad for abortions were murderers. Abandoned wives should have hung on to their husbands—and we still tipped our hats to the upper-classes and turned a blind eye to their failings. In the latter part of the decade, we discovered that our Taoiseach (Prime Minister) had been spending our taxes on racehorses, a yacht, and an island to impress his long-term mistress. The Bishop of Galway, who had personally greeted the Pope during his visit to Ireland in 1979, had fathered a child and used diocesan funds to pay off the baby’s mother. Church, state, and the law had let us all down, but most particularly, the women.

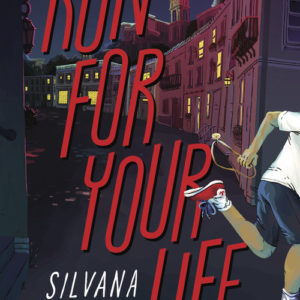

And yet look at the explosion of Irish female crime writers who were growing up during that time: Tana French, Alex Barclay, Jane Casey, Sinead Crowley, Jo Spain, Sam Blake, Louise Phillips, Niamh O’Connor, Claire McGowan, Arlene Hunt, Andrea Carter, Andrea Mara, Cat Hogan and Karen Gilleece among others. In a country this small, isn’t it extraordinary that so many of us have turned to crime? Women were silenced and imprisoned in their bodies and their marriages for too long. In the 1980s, the veil began to fall and we saw the truth. You’re never going to shut us up now.