My love for comic books began in 1970 when I was seven years old and my babysitter’s nephew named Drew, who was a few years older than me, shared his stash of Marvel Comics. That Saturday night I stared eagerly at the four-color pages spread out on the floor of that Riverside Drive apartment, their glossy covers bearing the names of The Hulk, Doctor Strange, Captain America, Silver Surfer, Daredevil, Thor and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.

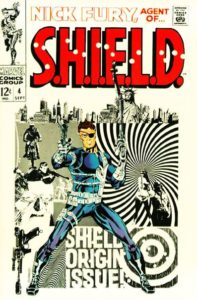

Flipping through Fury’s newsprint pages, I was transported into a modern day, yet futuristic landscape of espionage, killer robots, baddies working for an evil agency called HYDRA, pin-up beautiful women and the coolest weapons on the planet. In those days the medium was macho and Nick Fury was a man amongst men. While I had no idea who drew those striking Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. covers, the designs reminded me of the James Bond posters I admired dearly. The images were vibrant and seemed to leap from the page. Later I learned that those eye-popping graphics were the work of artist Jim Steranko.

***

The day after Thanksgiving, 1977, I awoke at dawn, excited about the attending the annual Creation Convention. Leaving the house with a knapsack, inside were a few shopping bags and a spiral artist’s pad so I could buy sketches from creators. After riding the graffiti scrawled subway to 34th Street, I was soon pushing my way through the crowds emerging from Penn Station and the holiday shoppers headed towards Macy’s. Within minutes, I was standing in front of the Hotel Pennsylvania’s massive pillars and pushing through the revolving doors.

With its high ceiling and plush couches, the lobby was already crowded with other overanxious convention customers milling about as well as vendors carting boxes merchandise onto the elevator. Far from the luxury of its heyday when Glenn Miller played in its ballroom, the 22-floored hotel, much like the city itself, had seen better days, but even in its shabbiness it was majestic.

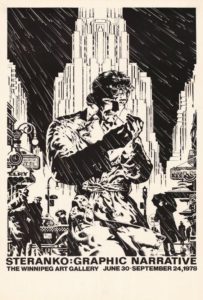

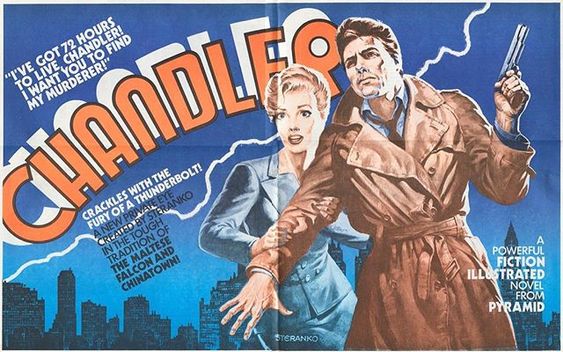

I walked through the crowded gathering and slowly absorbed the overabundance of comics, original art, trading cards, animation cels, slides and Star Trek products. Moving to the center of the room, I found myself in front a huge table covered with various materials. Behind the table was an immaculately dressed gentleman with movie star looks and hair that rivaled Elvis. He was selling copies of a stylish newspaper called MediaScene, two volumes of The History of Comics, an illustrated calendar of female pin-up superheroes called SuperGirls, an art portfolio of Mike Hinge drawings, a poster for a barbarian character named Talon and the digest-sized crime comic Chandler that was, arguably the first graphic novel.

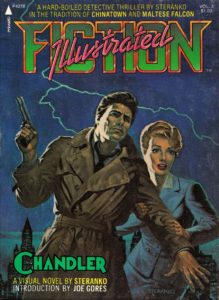

The cover was dominated by blues and showed a noirish, gun-toting P.I. wearing a raincoat and ready to protect a distressed damsel as a lightning bolt crackled over their heads. On top of the book in yellow type it read, “A hard-core detective thriller by Steranko.” It took a few seconds for my brain to register the name, but then I almost screamed when I realized that this was the artist I’d fallen for that fateful afternoon when I saw the Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. issues on Drew’s bedroom floor.

For a moment I just stared at him, as the man himself flashed me one of his trademark Kodak smiles. With his jet black perfect hair, G.Q. wardrobe, sunglasses and spit-shined boots, he was iceberg smooth. “How you doing over there,” Steranko said in his world’s greatest showman voice. I shyly glanced at him and back at the Chandler cover when I suddenly realized that the picture of that mean streets private dick was actually a self-portrait.

Picking-up the digest (there was also an 8½ x 11 version), it was apparent that it was far from the average comic in terms of panel layouts with the books narrative on the bottom of the art. In the era when mainstream comics cost thirty-cents, I gladly paid the dollar cover price. This was many years before I’d read Raymond Chandler’s novels or sat in through any John Huston crime features, and Steranko’s book served as one of my introductions to the silhouettes and shadow landscape of noir.

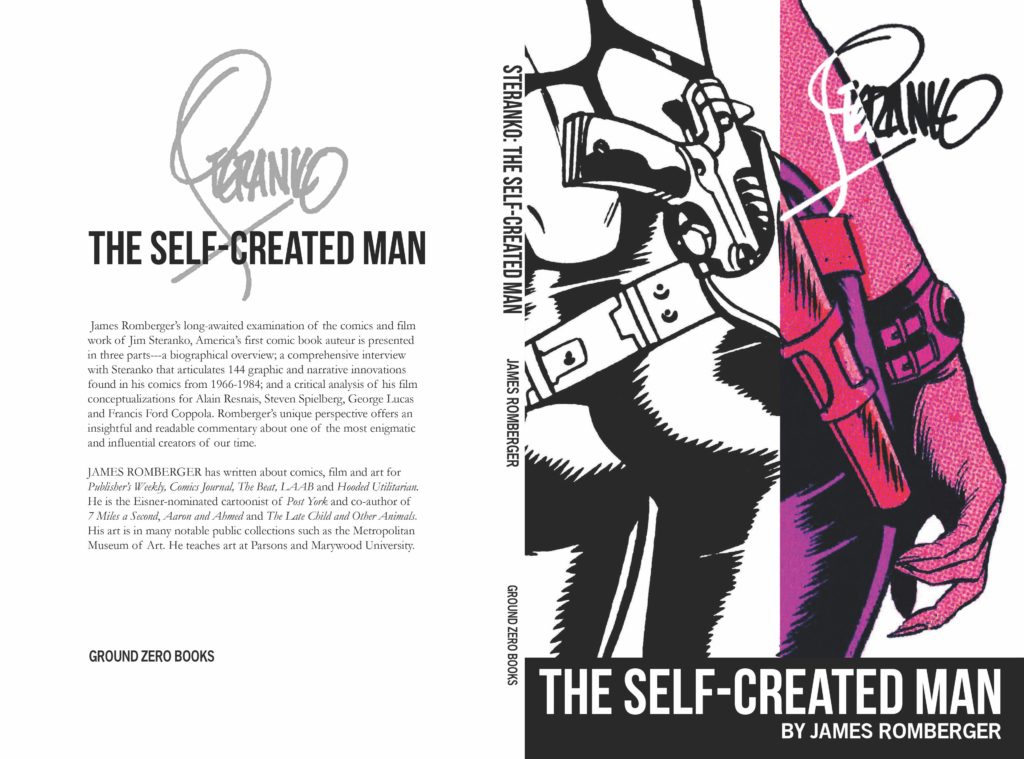

In Steranko: The Self-Created Man, a wonderful book published last year by Ground Zero Books, author/publisher James Romberger has a lively discussion with the artist on why Chandler should be considered the first graphic novel as opposed His Name Is… Savage (1968) by Gil Kane or Contract With God (1978) by Will Eisner. In addition, in an interview conducted through email, Romberger told me that Eisner, the creator of The Spirit and a brilliant pioneer of the art form, spread the misinformation that Steranko traced Chandler from photos. “That isn’t true and it is a shitty blow to a competitor for what Eisner sees wrongly as his own claim to creating the first graphic novel.”

For me Chandler, which I think of as Steranko’s masterpiece, was my gateway into the shadowy world of pulp sensibilities in film noir, crime novels, and the paintings of Walter Baumhofer, Rafael DeSoto and Norman Saunders. The book was the third in Fiction Illustrated series edited by Byron Preiss, who also wrote the other publications that included Son of Sherlock Holmes drawn by Ralph Reese and Schlomo Raven: Public Detective, a collaboration with Tom Sutton.

“When I made the deal with Byron,” Steranko stated in a 1978 interview, “I said, ‘If I can’t come up with a new experimental format that works, I won’t do the book, because I’m not interested in doing just another comic, another Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D…the format adds greatly to the story since it forces the reader into a measured rhythm, two illustrations to the page, pacing the action very steadily.”

If Steranko’s superhero work was visual rock and roll, than Chandler was big band jazz. Decades later, we can see Steranko’s art influence on contemporary crime comics including Frank Miller’s Sin City, Darwyn Cooke’s adaption of Stark’s Parker series, Eduardo Risso’s 100 Bullets as well as the virtuoso volumes of illustrated noir drawn by Sean Phillips.

For me, as well as other fans, Steranko’s groundbreaking art defined sixties cool and seventies spy swag as much as John Barry’s scores, Tom Wolfe’s journalism, stacks of Playboy magazine, Pauline Kael criticism, chilled martinis, Sly Stone singles, James Baldwin’s essays and books by Norman Mailer. To this day, I still flip through “Red Tide” for inspiration while working on my own neo-noir tales.

These days, at eighty-years-young and looking more fit than men half his age, Steranko retains a retro hipness that reminds me of an aged Roger Sterling from Mad Men. Every few years he returns to the comics, dazzling the fans with his visual voodoo as he did with innovative graphic novel adaption of the film Outland in 1981, an wonderful ten-page Superman short story in 1984 and, and, most recently a variant cover for the milestone Detective Comics #1000. Still, there hasn’t been a new full-length Steranko comic in decades.

***

Fifty-three years after Jim Steranko launched his comic book vocation with Strange Tales #151 (Dec. 1966), his career and life are the subject of a splendid monograph Steranko: The Self-Created Man written by James Romberger, a talented writer, graphic novelist, pastels artist, Parsons School of Design professor, publisher and longtime East Village resident. Romberger was born in Long Island, but raised in upstate New York where he discovered Steranko’s work on a newsstand in Oneonta.

“I was riveted by the color, the page designs, the dramatic psychedelia,” Romberger says via email. “At some point I started to also notice Kirby, Toth and other artists with unique styles. I tend to like artists with odd personal stylistic tics which made it obvious that a human drew them. It made me realize I could do it too.” Moving to the Lower East Side in 1981, Romberger’s first published comic book story “In the Heart of the City,” written by Margaret Gallagher, appeared in Epic Illustrated #13 in 1982, he was later contributed to The East Village Eye, World War 3 Illustrated and 2020 Visions. In 2010 he illustrated the noir inspired Bronx Kill graphic novel for Vertigo.

The Steranko project streamed from interviews he conducted with the artist that was originally to be published in Comic Art Forum, a fanzine he and partner Marguerite Van Cook published. The zine had previously featured interviews with former Daredevil/Howard the Duck artist Gene Colon and film producer Barry Geller, the man who commissioned drawings from Jack Kirby for a film version of Roger Zelazny’s science fiction classic Lord of Light. Their publishing company Ground Zero also reprinted 7 Miles a Second, Romberger’s brilliant graphic novel collaboration with the late writer David Wojnarowicz.

Romberger finally met Steranko at the Big Apple Comics Con in 2002 and the men exchanged mutual admiration for each other’s work. “I asked him if I could interview him and he agreed,” Romberger explains in The Self-Created Man, a title that was meant to indicate that Steranko has made his own identity and way of living. “After that, we began a fascinating exchange of emails.” Steranko liked the sorts of questions Romberger was asking, and requested that Romberger go through all of his comics and articulate his innovative narrative techniques. “When completed, it seemed too substantial of an interview for a small Xeroxed zine, so I began to consider publishers.”

However, when faced with the challenge of writing a detailed introduction for the project, Romberger put the book on the back burner while he literally went back to school. “I really wasn’t versed in formal writing,” he says. “I had only gone to Art College. So, for that and other reasons, I went back to school to gain control of my writing. I wanted to not be so dependent on writers for my comics and also to articulate myself better.”

Studying at Columbia and CUNY led Romberger into critical writing about comics and film for Publishers Weekly, The Comics Journal, The Hooded Utilitarian and The Beat. He has written about Alex Toth, Hugo Pratt and Seth Tobocman. Eventually, he worked his way back to Steranko, producing a text that celebrates and educates.

Steranko is a second generation Ukrainian immigrant from Reading, Pennsylvania, he was born on November 5, 1938. Raised in poverty, he escaped the dreariness of his family’s post-Depression era life through the Sunday comic strips of Hal Foster (Prince Valiant), Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon), Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates) and Frank Robbins (Johnny Hazard). In addition, his Uncle Eugene brought him bags of comic books, and he devoured the panels of Jack Kirby, Reed Crandall and Wally Wood.

“After seeing Wally Wood, I was never the same again,” Steranko said on a convention panel in 2014. “Woody could do everything and do it superbly.” Steranko was soon teaching himself to draw on old envelopes. During his teen years, he perfected being an escape artist while also dappling in juvenile delinquency that involved stolen cars and guns. In 1971, he told former Marvel employee turned Rolling Stone writer Robin Green, “Eventually they caught me and I had to give up, my guns. I had many guns. A complete arsenal. My two pearl-handled .38s, 30 pistols, and countless rifles, we had .45s, and a submachine gun that shot nine millimeter parabellum shells…I was only in jail until my trial, about a month, and they had me in solitary with a 24-hour guard because of my history as an escape artist…I was placed on probation…I was still a juvenile delinquent at the time.”

Steranko’s real-life escape artist adventures have been appropriated in the fictions of Jack Kirby’s 1970s character Mister Miracle and Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. After going straight, Steranko’s colorful list of jobs reads like the biography of a 1930s novelist. In his lifetime he’s been a magician, carny, escape artist, a boxer, bodybuilder and a card trick master. Ever the hustler who could talk his way into whatever gig suited his tastes and self-taught talents, Steranko was soon working as a graphic designer at Milford Associates and played in various Pennsylvania-based rock bands, but he never lost his love for comics.

Working briefly as an inker for Matt Baker and Vince Colletta in late-50s, Steranko was regulated to the background of the comics industry for a few years. It wouldn’t be until he met veteran artist/editor Joe Simon, who was Jack Kirby’s former partner and the co-creator of Captain America, at an early comic book convention in 1966 that his luck began to change. Simon invited Steranko to create characters and write comics for Harvey, who’d introduced a line of superhero books, but he was unimpressed with cool cat’s art.

A few months later, Steranko took his portfolio to Marvel Comics. He was twenty-eight years old when he wandered into their Madison Avenue offices and charmingly bogarted his way into Stan Lee’s office. Lee, excited by Steranko’s “raw energy” hired him on the spot and offered him whatever book he wanted. The artist chose super-spy Nick Fury. Not to be confused with the present day Fury who looks like Samuel Jackson, the original was a white guy World War II veteran called Sgt. Fury who later became a Cold War protector.

“After drawing over Kirby’s layouts for three issues, Steranko was handed the reins—solely generating not just the art, but the scripts as well,” author Sean Howe documented in his 2013 book Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. Later he contributed to the legacy of Captain America and Hulk, but it was his vision of Fury that became tattooed on the brain of a generation. “I brought my design chops, those skills, into the comic book world,” he told interviewer Alex Grand from Comic Book Historians podcast in 2018 . “Typography, design, composition.”

Proving to be a diverse stylist and rule breaker, the majority of Steranko’s work was superhero books, but he also contributed horror and love comics that were as radical as his costumed adventurers. “Steranko gets props for unique graphics that considered the panel layouts every bit as important as the art within them,” writer R.C. Baker says. “He wasn’t unique in this—Eisner was a trendsetter, Bernie Krigstein was a layout virtuoso, and of course Kirby at his best, did it the way the rest of us breathe. But Steranko pulled that idea into the 60’s, early 70s, which I would argue is the Golden Age of comic book art.”

Unfortunately, this early work was done during the era when comics and their creators weren’t taken seriously. Comic book artists were low-paid, their artwork wasn’t returned and, working under notorious work-for-hire contracts they were given zero residuals or royalties for any of the characters they created. When comics from that era are reprinted or turned into films, neither artists nor writers receive a dime. Marvel has constantly reprinted Steranko’s work without compensating him. On the other hand, Steranko knew his artistic breadth and worth long before many of his contemporaries.

He challenged himself, indulged in experimentation and was as radical he wanted to be, but he also knew when to get out of the industry. Steranko only illustrated twenty-nine stories for Marvel, the same amount of songs that premier bluesman Robert Johnson made in his lifetime. “Robert Johnson sold his soul to the Devil; I sold mine to Stan Lee,” he sometimes jokes.

“The comics are not a very popular medium, even when I entered this field,” Steranko said in 2005. “They spoke a dead language, they still used the visual syntax of the press strips of the 30s. The editors, writers and cartoonists did not realize that their Style was dying because it had hardened arteries and needed a transfusion of fresh blood and new ideas. Many of the cartoonists who worked at that time were old professionals who had become human photocopying machines, who simply repeated the same ragged clichés, number by number.”

Steranko left Marvel after Lee messed with his text for the stunning horror story “At the Stroke of Midnight” published in Tower of Shadows #1. Says Romberger, “The fact that he quit and began to self-publish when idiots fucked with his work was significant. He knew he’d done something good and just decided that he didn’t need to suffer fools gladly. It sucks that a guy as brilliant as Jack Kirby felt he had no choice but to eat all the abuse he got wherever he went. Steranko pointed the way to freedom.”

Unlike fellow maverick artist Neal Adams, I don’t recall Steranko being publicly outspoken about creator’s rights or helping to form Comic Book Creators Guild, but he did guide by example. His media company Supergraphics published the magazine ComixScene, which after six issues became MediaScene, which later became Prevue, a leading film magazine.

Unlike fellow maverick artist Neal Adams, I don’t recall Steranko being publicly outspoken about creator’s rights or helping to form Comic Book Creators Guild, but he did guide by example. His media company Supergraphics published the magazine ComixScene, which after six issues became MediaScene, which later became Prevue, a leading film magazine.

In addition to publishing, editing and writing articles, he also provided beautifully illustrated covers and centerfolds for his publications. Supergraphics produced several projects and Steranko also churned out paperback covers for The Shadow reissues as well as books by Leigh Brackett, Michael Moorcock and L. Sprague De Camp. In 1972 DC Comics offered Steranko the opportunity to draw The Shadow comic, but he wanted to write the book too, so the art chores was eventually handed to relative newcomer Michael Wm. Kaluta.

***

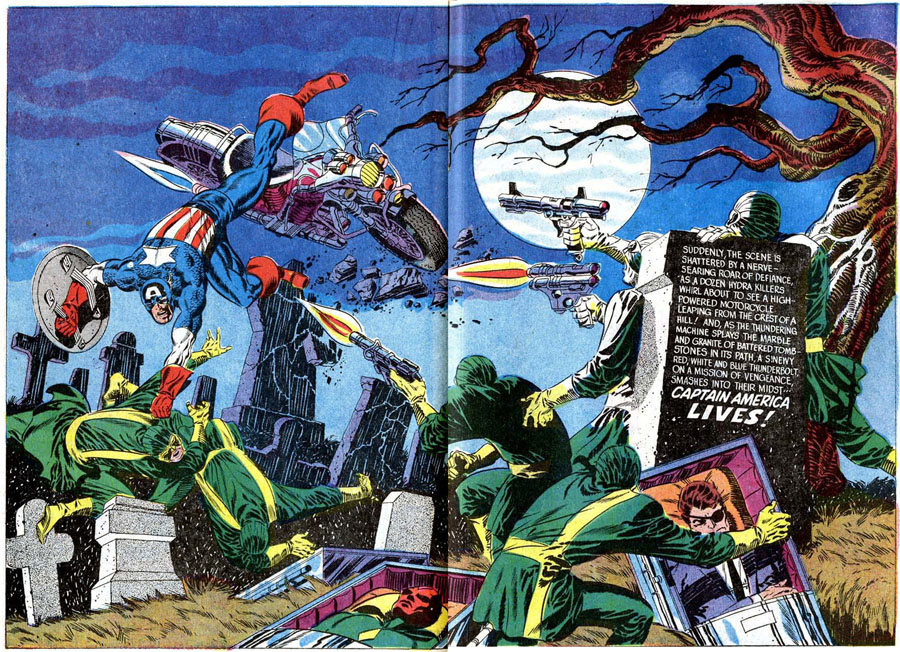

In Steranko: The Self Created Man, Romberger, makes the case of the brilliance and importance of his subject as not just a premier artist, but as someone who has helped expand the language of graphic storytelling with 144 innovations that has inspired numerous artists including Frank Miller, Howard Chaykin, Eduardo Risso and Tim Fielder. “I didn’t study Steranko, I copied Steranko,” Matty’s Rocket creator/artist Tim Fielder says from his Harlem home. “Seeing that double-page spread of Cap on a motorcycle in the cemetery (issue #113) changed my perception of what was possible within sequential art. Steranko gave permission for artists to be cinematic. Few other artists have had as much of an impact on me.”

Steranko’s own love of film noir helped fuel his own passion which he poured onto the Bristol board with widescreen/ Technicolor boldness. “I spent an enormous amount of time in movie theaters,” Steranko told interviewer Alex Grand. “My storytelling sensibility was formed completely by the world’s greatest directors–Hitchcock, Orson Welles and John Ford.” Unlike film directors, Steranko didn’t need lots of money to build extravagant set, just his pencils. “On each page I could create a million dollar set.”

Additionally, we can even see a bit of movie titles master Saul Bass in Steranko’s work, especially in his anti-drug comic The Block whose graffiti wall first page was reminiscent of the credits sequence of West Side Story. Steranko would later put those skills to work on various cinematic projects including Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg) Bram Stoker’s Dracula (Francis Ford Coppola) and un-produced film biography about Marquis De Sade that was to be directed by Alain Resnais.

“Comics have been inspired by cinema since the 1940s, which you can see in the work of Will Eisner and Jack Kirby,” says cultural critic/former comic book nerd Greg Tate, “but Steranko also mixed in influences from pop, psychedelic, Op art, surrealism and graphic design. He brought finesse, polish and sophistication that was fresh. He wasn’t beholden to any orthodoxy about comic art.”

Since fine artists swiped from comics then Steranko had no problem swiping from them with pages and covers that severed as homage to Salvador Dali, M.C. Escher and Peter Max. In sense, it was as though Steranko’s art was having revenge on Roy Lichtenstein and others of his ilk who built their careers appropriating the comic book art of Russ Heath, Joe Kubert, Gil Kane and John Romita. Recently I’ve seen Batman pictures he’s drawn in the style of Picasso, which still retains the essence of Steranko.

Graphic designer/comic book historian Arlen Schumer has called Steranko “the Jimi Hendrix of comics,” and, considering his boldness and unconventional attack, I agree. “I can remember reading those Steranko books and every page you turned, your mind would be blown,” Living Colour guitarist and lifelong comic collector Vernon Reid, who has also has also been compared to Jimi Hendrix, says. “Even the way he drew panels, nothing was simply contained in a box, things would spill over. Everything he did was hyper-modern and daring with a terrific sense of movement in the robots, car chases and fire fights. Certainly, I can see his influence in the next generation, like Bill Sienkiewicz or in a film like the first Matrix, which to me looked like Steranko storyboarded it. My favorite comic artists are Jack Kirby, Neal Adams and Jim Steranko, because they were like film directors. On the page, those guys were auteurs.”

In 1970, Supergraphics published volume one of The Steranko History of Comics, which featured an introduction by famed director Federico Fellini; volume two came two years later. Coming at a time when there wasn’t much reference material about “the comics scene,” it was a hip yesteryear trip. “It was the first entity I came across that made me realize what a terrific art form comic books were,” says R.C. Baker, “and I will be forever grateful to it for introducing me to Will Eisner’s (seminal character) The Spirit.” There were supposed to other volumes, but those books joined the list of promised, but so far un-produced Steranko projects that includes his creations Talon and O’Ryann’s Odyssey.

I must admit it was disturbing to read in Romberger’s text that Steranko was vocal Trump supporter who “…commented repeatedly on Twitter in support of the NRA and Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton and her alleged ‘criminal associates.’” Closing my eyes, I silently wished I could’ve unseen the fact that another of my artistic champions, much like Clint Eastwood and Johnny Rotten, could possibly support a racist, heartless, egotistical President who has admittedly sexually harassed women, praised Nazis and brags about being smarter than everyone including intelligence agencies.

While I’m as conflicted over Steranko’s political stance, writer Greg Tate says, “There is a history of artists who are radical in their work becoming arch Republicans. As they got older they start feeling as though the world is spinning out of control and they begin to embrace the most conservative shit they can find.” Meanwhile, Romberger, who could be described as a Leftie radical, writes, “Steranko’s work must be assessed on its own merits.” Though I will admit to missing the days when people didn’t talk about politics in public, as Sly Stone sang, “Different strokes for different folks.”

Steranko: The Self-Created Man was written with a fan’s enthusiasm and a professional’s perspective. Romberger gives the reader a better understanding of process and influences behind Steranko’s stunning style as well as the man standing next to the Bristol boards and paintings. For all the new respect bestowed on comic art from curators and art critics, there aren’t many books that attempt to analyze the work of the genre’s living legends and The Self-Created Man takes us there.