My favorite game as a child was Clue. I loved the aesthetic, the hard board that evoked a grand old house. The implicit glamour of it, with its ballroom and library and billiard room. I could almost smell the tobacco, feel the plush texture of the lounge, hear the footfall on marble floors.

I had an appetite for bloody mystery, loving the puzzle of who did it with the candlestick in the conservatory. I devoured Agatha Christie novels too, more murders in fancy houses, from my early teens after seeing how taken my mother was with them. Murder was to me a game, a puzzle, a story.

Then, when I was fourteen a neighbor was killed in his home a little more than fifty meters from where I slept. He’d been murdered. By a lover, with a knife, in the kitchen.

Our neighborhood was quietly suburban. Tidy single story houses, with neat front gardens, in the last years of apartheid South Africa. Not affluent, nothing like the large houses in leafy streets you’d find in the “whites only” neighborhoods. But it was well-kept, almost anxiously so.

Across the road was a field covered in brown scrub, where we’d play imaginary games involving soldiers and wars when younger. Behind was a row of factories, severe looking buildings that we’d learned to ignore.

Was it imagination to play games involving soldiers, when you’d seen real army tanks patrol your streets? When oppression and uprising was as much a part of your childhood as the sharp angled factory rooftops with their smoking chimneys?

And yet, despite the underlying political turmoil, our quiet neighborhood had always felt safe. Ordinary. It was what we knew.

The news of the violent knife attack was an abrupt shattering that tore through our area. It put us on edge in a way we hadn’t been before. A man had been killed in his kitchen, following an argument with a romantic partner. Suddenly murder wasn’t a game or a story to me anymore.

Until then, violence had always been something that happened elsewhere. But in this shocking death, my understanding of the world changed. It momentarily fused the divide between story and the real in a way that forever changed my perception.

It showed me that bad things happened behind the drawn curtains of nearby houses. That we didn’t always know the people we saw every day.

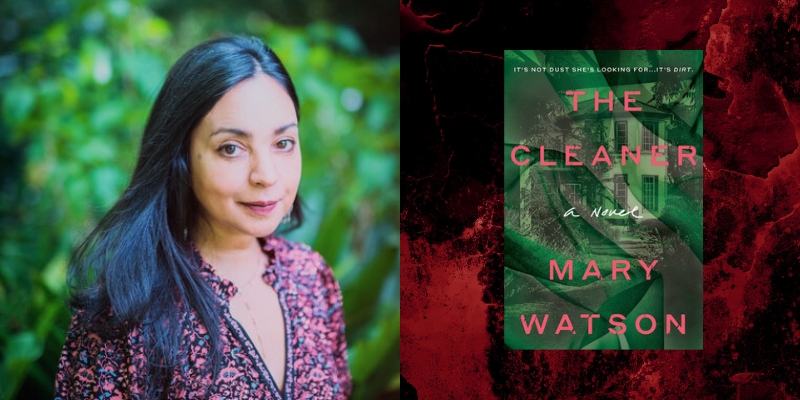

It gave me a glimpse of how intimacy could turn from love to hurt. This discovery of the quiet violence hidden behind closed doors, would later become the point of departure for my adult thriller, The Cleaner, where a young woman poses as a cleaner to gain access, learn secrets and exact revenge.

There were many questions, following the murder. More than who did it, I wanted to know why. Not the intricacies of their argument, but why murder? What happened to that person as they picked up that knife that night? What went through their mind?

It was around this time that I read Lord of the Flies. I remember that book like a fever dream—the boys on the island, the growing fear, the savage awakening.

But what I remember most is the end, when Ralph weeps for “the darkness of man’s heart.” And this, I think is what my first brush with murder brought to me, a deeply felt awareness of the darkness of our hearts. A knowledge, in my bones, that humans have an inherent capacity for harm. That the sinister can lie sleeping within the ordinary. That uncrossable lines maybe be transgressed and redrawn.

Recently, I’ve been revisiting the Agatha Christie novels I first discovered in my teen years and have reread over time. I’ve been listening to them as audiobooks, while cooking dinner or folding laundry, or some other domestic task.

My children listen to snippets of these murder mysteries, not as taken by them I as was at a similar age. In these stories I now recognize a similar enduring fascination that drives my own writing, what lies at the heart of The Cleaner: how ordinary people living ordinary lives may do terrible things.

And, in an increasingly bewildering world, I think of Ralph, weeping for the darkness of man’s heart. There’s a line there for me, forged decades ago, that draws together midnight tragedy and story and a world that can be unjustly harsh even as it is mundane.

***