Researching my historical mystery novel The Betrayal of Thomas True required me to go to some very murky places, and there are few places in Georgian London so very dark as a stretch of scrubland to the East of London. Tyburn was no stranger to the cries of a baying mob, being home to the executioner’s gallows for generations, but on May 9th, 1726, there was more than just the usual cartload of criminals being trundled there in shackles.

The sight of a murderess, her hands bound, preparing for the agony of being burned at the stake for killing her husband was promising, as was the hanging of her two male accomplices who’d chopped up their victim’s body with an axe.

But the biggest draw at Tyburn, where the gallows’ beams were worn smooth by the rubbing of ropes from the dangling dead, was the execution of three men for the diabolical ‘sin’ of sodomy. They were soon to entertain the crowd with their death throes, known—with typical gallows humor—as ‘a Tyburn jig’.

I sat in the silence of the London Library, surrounded by leatherbound books and walnut bookcases, feeling a cold stone settle in my stomach as I read accounts of what happened next. What those men went through was lost to the distant past and yet, to me, it felt immediate and no less disturbing than if I’d been one of their friends, come to Tyburn to bid them farewell.

I had been writing my mystery for two years and the characters in my book were like friends to me. I didn’t want them to hang, but I knew it wasn’t my choice. History, and my characters, were in charge now, and all I could do as an author was follow them. I’m fortunate to count the novelist and matchless historical and contemporary researcher Patricia Cornwell as a mentor and she explained to me once: ‘You have to sit in front of your characters and ask them what they’re going to do next. Listen and they’ll tell you; ignore them, and they won’t bring your book to life.’

Thomas True and Gabriel Griffin are my beloved main characters, caught in a race against time to unmask a murderous traitor before they are caught and forced to hang. Following Thomas and Gabriel through their breathless adventure has been an honor and they most certainly brought the world of the mollies to life. And yet, now the real-life men who inspired them were facing a terrible death…

The titillation of the packed crowd was palpable on that Spring day, some three centuries ago. Many of the mob were drunk and shouting, flinging punches at each other to secure the best view. The wealthiest onlookers had paid good money to be crammed in on a looming collar of raked pews reaching up into the sky, like the benches of a theatre.

The three condemned men who were to have their agonies applauded all the way to Hell were Gabriel Lawrence, a 43-year-old milkman and single father, William Griffin, a 43-year-old upholsterer fallen on hard times, and Thomas Wright, a 32-year-old wool-comber.

Each of them had been found guilty of—to quote court records—‘the heinous and detestable Sin of Sodomy, not to be named among Christians’. They were arrested in a raid one Sunday night in the February of that same year at a secret meeting place for gay men named Mother Clap’s Molly House. A squadron of constables had descended on Field Lane in Holborn, a street which would achieve notoriety some hundred years later when Charles Dickens set Fagin’s lair from Oliver Twist in the very same slum.

In burst the Society constables, discovering a set of rooms tucked away between an archway and the Bunch O’Grapes tavern, their associates blocking the passageways around the house to prevent the startled men from escaping. By the early hours of the following morning, some forty unfortunate ‘sinners’ were locked up in the fearsome Newgate Prison, awaiting trial. Thanks to the archives and historians who have studied the often muddled and redacted records, I was able to build a time machine, returning to catch a glimpse of this defiant underworld.

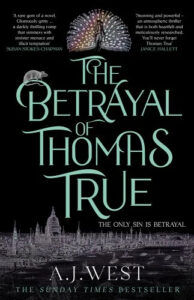

Most of those arrested were let off after their imprisonment for lack of evidence, but the arrest, trial and execution of three of them—thanks to the testimony of masked traitors—formed the inspiration for my latest mystery thriller novel The Betrayal of Thomas True.

The raid on Mother Clap’s was part of an orchestrated attack on gay subculture, inspired and supported by an organisation known as The Society for the Reformation of Manners. This self-appointed religious group of moral fanatics was responsible for a network of paid informants and enforcers with tentacles stretching deep into the city’s underworld, ostensibly suppressing profanity, immorality and other lewd activities by force. Led by the clergy, business leaders, the gentry, the judiciary and politicians, the Society enlisted men and women from all walks of life to join their ranks. They bribed homosexual men to turn traitor, while some of their agents posed as mollies themselves to get a firsthand peek into the secret meeting places.

What did they see inside Mother Clap’s? The Society had been carrying out surveillance since at least the previous November, and one of the Society’s agents, a man named Samuel Stevens, had inveigled himself inside, disguised as a molly.

Homosexuals at the time were commonly called all sorts of names. ‘He-whores,’ was one, ‘buggerantoes,’ another, while the pious liked to refer to them as ‘notorious sodomites’. The most common term, however, was ‘molly’.

Mister Stevens says he went to Field Lane and discovered: ‘…between forty and fifty men making love to one another, as they call’d it.’ He goes on to recount a convivial scene in an open room with a fiddler playing music, the space packed with men kissing and ‘using their hands’. He then gives us an all-too-rare taste of what eighteenth century mollies might actually have sounded like and this, when I first read it, was like an explosion of inspiration. ‘They would get up, dance and make curtsies,’ he recounts, ‘and mimick (sic) the voices of women.’

Stevens goes on to describe the men retiring to other bedchambers, cheekily known as ‘chapels’, where they would either close the door, or leave it wide open for the titillation of the spectators. Mother Clap was present throughout, apart from when she was dashing next door to replenish the liquor.

Stevens’s testimony feels simultaneously alien and familiar. Any gay man reading this article might recognize the barbed compliments, the sexual innuendo and the flamboyant mimicry of bawdy female alter-egos, but the surrounding culture, daily routines and societal mores were a barrier, preventing me from stepping back in time. It was also far too easy to make assumptions and judgments about the people appearing in the archives.

Any crime novelist requires good characters and evil characters of course, and I had an abundance of inspiration for both. Mother Clap, owner of the establishment of the same name, showed considerable bravery in her lifetime, putting her neck on the line more than once in court to give false testimony for mollies facing the noose, while apparently making little to no financial profit from her house of ill-repute. Meanwhile, the blackmailing hounds of the Society repulsed and angered me with their hypocrisy and lack of humanity. Still, I was too quick, I think, to cast the mollies as angels and the Society agents as devils. Of course, executing gay men was—and is—irretrievably stupid, pointless and evil, but this was a time when homosexuality was misunderstood, not as a natural attraction to the same sex, but as a willful perversion, a form of demonic, bestial misogyny. In a world where gay men are seen as such, it’s perhaps easier to understand—without sympathy—why mollies were feared and loathed by the hyper-religious society of the time. After all, we needn’t go back in time to see evidence of the very same attitude, we need only travel to countries around the world today where gay men are demonized in the name of religious piety or claims of poisonous immorality.

Another false assumption I made was that women sex-workers might automatically have been allies, sharing the yoke of oppression and abuse. In actual fact, female prostitutes were some of the most violent and vitriolic attendees when mollies were publicly punished.

Meanwhile, some of the mollies themselves were guilty of questionable acts. One named Mark Partridge appears to have turned traitor for bribes or to save his own neck after falling out with a friend who was indiscreet about his sexuality. Taking Society agents on a tour of molly houses, he is surely responsible for the ruination of a great many of his supposed friends.

It’s a truth universal that I wanted to reflect in my book, that evil comes in all forms and being part of an oppressed minority doesn’t necessarily make someone kind or honest. As my lead character Gabriel Griffin says in The Betrayal of Thomas True: injustice does not make a man kind. Meanwhile, there can be good people, even in the cruelest of institutions.

We return then to Tyburn, where our three mollies perch at the rear of a cart, their ropes slung over the beams above their bowed heads. Gabriel Laurance could be forgiven for thinking himself particularly unfortunate. Though sodomy was of course very much a capital offence, none of the condemned men had been caught in the act, the jury choosing to believe the questionable testimony of a traitor. Executions were sporadic and rare in the 1700s and in Gabriel’s case, a number of people had testified for him in court, not least his father-in-law who spoke fondly about Gabriel’s 13-year-old child who was to be orphaned. And then there was his friend of eighteen years, Henry Yoxan, a cow-keeper who told the jury: ‘I have been with him at the Oxfordshire-Feast, where we have both got drunk, and then come Home together in a Coach, and yet he never offered any such Indecencies to me.’

Laurence even had two dukes and an earl petitioning the King for his life, pointing out that the evidence was tarnished because it was based on that dastardly molly-turned-informant, Mark Partidge. They successfully obtained a reprieve for the condemned man at the last moment but alas, members of the clergy stepped in—including the Bishop of London and the Archbishop of Canterbury—insisting that he was hanged. They got their way.

And so, to the almighty roar of the crowd, the cart rolled forwards and the three convicted men were hanged, nobody pulling on their legs to lessen their agonies.

When I wrote about them in my novel, sitting in the London Library, I shed more than a few tears thinking of the terror and deep sadness those poor men must have felt that May afternoon, leaving a cruel and violent world behind to the sound of cheering.

Ah, but the real-life story behind my novel doesn’t quite finish there. While the convicts bade farewell to the world, bouncing on their ropes, the raked viewing platform behind them began to crack and splinter and in an explosion of nails and wood, the whole structure collapsed, maiming many and killing sixteen of the spectators in an instant. It’s only my speculation of course, but perhaps God wasn’t quite so supportive of the executions as the Society for the Reformation of Manners assumed.

It is just one of so many mysteries woven through the true story of Mother Clap’s molly house. The Betrayal of Thomas True borrows from them all, wrapping them all around one central puzzle. Just like in the history books, there is a traitorous Rat giving the mollies’ names away to a pair of murderous justices and Gabriel and Thomas must unmask him before before they’re forced to dance the Tyburn jig. In the world of the mollies, betrayal is the only sin and time is running out…

***