Boris Morros fit in easily in Hollywood. Like so many transplants from the East Coast, he marveled at the way doors that were closed on Wall Street, Main Street, Madison Avenue, in the Ivy League, and even on Broadway were open in Hollywood. The fact that Hollywood’s aristocracy was composed of Jewish immigrants—fifty-three of Hollywood’s eighty-five major producers were Jewish when Boris arrived—made things even easier.

Despite their wealth and prominence, William Fox (born Wilhelm Fuchs), Louis B. Mayer (born Lazar Meir), and Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz), not to mention Jack Cohn, Harry Warner, Jesse Lasky, and Carl Laemmle, were determined to be seen as real Americans, a sentiment that Boris implicitly understood. Their patriotism was a matter not just of eating pork, working on the Sabbath, marrying their children off to gentiles, and voting Republican, but of making as much money as possible. Hollywood’s religion was social mobility, and Boris got moving, starting with the purchase of a luxurious home at 915 North Beverly Drive, off Sunset Boulevard. The thirty-five-hundred-square-foot stucco house, which had seventeen rooms and a swimming pool out back, was just around the corner from the Beverly Hills mansions of Edward G. Robinson, Samuel Goldwyn, and Louis B. Mayer. But Boris was rarely home.

Because Boris was such a hard worker, it took Zukor five people to replace him in New York: a head of deluxe operations, a stage-show producer, a musical director, a talent booker, and a managing director for the theater. In Hollywood, Boris was busier than ever. While Catherine slept late and had nothing to do all day, having handed the responsibility of raising Dick to nannies, Boris got up early seven days a week and was often the first employee through the famed Paramount gate. A short walk across the massive complex, which had its own hospital and fire department serving thousands of employees, brought him to his suite of offices. Most of Boris’s time was spent at his desk with his ear glued to the telephone, hiring and firing composers, arrangers, and musicians. He was infamous for avoiding memos, no doubt because his written English was so poor. Still, despite being celebrated in the press as one of “more than a score of nationally known composers” who were bringing Paramount back to profitability, Boris wasn’t writing much music, though he did insist, unlike the music directors at most other Hollywood studios, on conducting the scores himself at Paramount’s enormous scoring stage.

The national press marveled as Boris, within weeks of his arrival, supervised the composers Frederick Hollander, Leo Robin, and Ralph Rainger in a fifty-six-song writing marathon that resulted in the score for Bing Crosby’s new picture, Rhythm on the Range. Boris served as music director for no fewer than thirty-eight films in 1936, and it wasn’t unusual for him to be simultaneously supervising three full orchestras, plus a choir or two. He later recalled: “Everybody needed me. Everybody wanted my advice.” On a typical day, Bing Crosby or any number of actors, singers, musicians, composers, directors, or producers might drop by for conversations that would inevitably be interrupted by phone calls summoning Boris to the soundstage to fix a song, or to a shooting set to coach a singer. No matter what the occasion, Boris could be seen playing with the amber worry beads supposedly given to him by Rasputin.

___________________________________

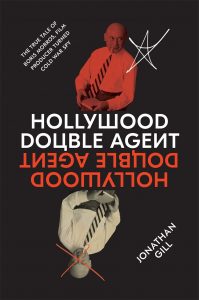

You are reading an excerpt from Hollywood Double Agent: The True Tale of Boris Morros, Film Producer Turned Cold War Spy by Jonathan Gill (Abrams Press, 2020)

___________________________________

When the workday, which might be as long as sixteen hours, was over, it still wasn’t over. Boris hurried home, where Dick would be relaxing by the pool after his daily round of golf at the Hillcrest Country Club. Having inherited his father’s negotiating abilities, if not his work ethic, Dick had convinced Beverly Hills High School that golf fulfilled his physical education requirement. Catherine, uninterested in the shopping, socializing, or philanthropies that filled the days of so many wives of Hollywood executives, had spent yet another day on the sofa with her gossip magazines. She hadn’t even made dinner: The Danish cook who lived with them did that. Mealtime was often uncomfortable in the Morros household. Catherine made sure that Boris knew how unhappy she was that he was gone most of the time, but she also didn’t want him around. Unable to articulate her resentment at Boris, who after all had given her a child, a house, and the free time to make a life for herself, Catherine was becoming bitter and angry.

Boris was happy to change into his evening clothes and leave Catherine behind again. After-hours, in nightclubs such as the Clover Club, the Mocambo, the Players, and La Boheme, or at the fundraisers or testimonials that were such an important part of the Hollywood social scene, Boris ate, smoked, danced, and mingled with the stars until late in the evening. Sometimes there was more work than play. As in New York, no gala, it seemed, was complete without Boris’s baton, especially when it came to Jewish causes. Boris directed the music at the June 1936 West Coast premiere of Land of Promise, the film about Zionist struggles to settle Palestine that he’d scored back in New York. The lavish show at the Biltmore Hotel, the fanciest space in the city, attracted Hollywood’s Jewish aristocracy, including David O. Selznick, Edward G. Robinson, and Paul Muni.

Boris wouldn’t have been able to take his place among Hollywood’s elite had he not been so good at his job. Just a few months after he settled into his routine at Paramount, Isabel Morse Jones’s Words and Music column in the Los Angeles Times was calling him a “new luminary in orchestra circles.” But the longer he stayed at Paramount’s music department, the more his classical music reputation suffered, and the more his old reputation as a “fixer” followed him. At Paramount, he introduced a number of innovations, such as scoring pictures while they were still in the shooting stage, and even having the actors speak their lines to the accompaniment of the score. But working on other people’s movies left him feeling unsatisfied. The weather in Southern California was beautiful, and he was making very good money at Paramount, but Boris wasn’t any closer to making his own movies. Still, he never lost the sense of thrill he experienced at seeing his name regularly in both the gossip columns and the trade journals. That’s not to say the press always took him as seriously as he would have liked. The most widely read syndicated newspaper columnists of the day, not just the “unholy trio” of Hedda Hopper, Louella Parsons, and Sheila Graham but also Ed Sullivan, Walter Winchell, and Dorothy Kilgallen, followed his every move at Paramount, from his meetings with talent and business trips back to New York to his acquisitions of individual songs. They followed him on his nightly rounds of the Sunset Strip clubs, and when by dawn’s early light he soberly scanned the morning papers—never much of a drinker, Boris was known to fill a vodka bottle with water and chug it all night long—he could count on seeing his name in bold letters, which was a mixed blessing.

There were many who saw Boris as Falstaff in Southern California. They laughed at his egg-shaped figure and mocked his taste in fashion, which ran toward patterns, stripes, dots, and checks, in every color of the rainbow, usually all at once. Still, Boris willingly collaborated with the press, which insisted on portraying him as a Jewish immigrant who would never fit in, never become properly Americanized, and whose horrendous accent inspired equal parts pity and laughter. Within three months of his arrival on the West Coast, Boris was already standing out in the crowd, with his orange silk shirt, light green suit, purple necktie, and plaid handkerchief, an outfit that was said to be a gimmick to promote Technicolor, but there was more than a grain of truth in the joke he used to deflect the ridicule: “How else would anybody ever notice me in this big place?”

Though Boris was now enjoying a level of success that he had often only dreamed of, it didn’t always come with the kind of professional legitimacy he hoped for. One of the very first projects he worked on in Hollywood, a Gary Cooper vehicle called The General Died at Dawn, won him an Oscar nomination for Best Score, a triumph tempered by the fact that the actual composing was done by someone else. Still, he knew how to stand up for himself. He convinced the famed conductor Leopold Stokowski to appear in Paramount’s Big Broadcast of 1936 and was unafraid to cross swords with the maestro regarding artistic matters: “What are you going to do,” Boris asked Stokowski, “argue with me about music?”

Zukor had his own ideas about what Boris was best at. When the Paramount chief celebrated his silver jubilee, a late 1936 event that was broadcast nationwide on Paramount’s radio affiliates, Boris reluctantly led the fifty-piece orchestra while Carole Lombard, Fred MacMurray, and hundreds of Zukor’s other close friends danced the night away. Boris was also less than delighted when Zukor asked him in February 1937 if he would like to produce, direct, and host a promotional thirty-minute radio show about Paramount behind-the-scenes that would be nationally syndicated via a deal with NBC. Boris thought he might make “Paramount on Parade” into a serious, almost journalistic series, but Zukor knew that Boris’s hilarious accent would be the real reason to tune in. As W. C. Fields joked on the front page of the New York Post: “Heard your program, Boris, and it was great. But why did you do it in dialect?”

Executives at ABC tuned in to “Paramount on Parade” and recognized a natural performer when they heard one. Impressed by Boris’s ability to connect to listeners, they gave him his own weekly syndicated program of classical music, featuring something called the Boris Morros String Quartet, an ensemble drawn from the ranks of the local classical music community. Clearly a bid to burnish Boris’s classical music credentials, the Sunday afternoon show ran throughout the first half of 1938. Of course, Boris’s continuing efforts to legitimize himself in the classical music world were undermined by his almost weekly participation in the musical portion of fundraisers and awards dinners. His attempts to recruit “real” classical composers, including Schoenberg, Rimsky-Korsakov, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky (who, like many Russian classical musicians visiting Los Angeles, stayed at Boris’s home), to write music for Paramount failed. Boris had ways of compensating: He planted an item in Film Daily that said the French government was planning to make him an “Officier d’Académie,” also known as the Silver Palm, for his contributions to French culture. The problem is that there’s no record of Boris ever receiving that distinction. Boris, it seems, could convince anyone of anything, except the Soviet secret police.

* * *

“For many years,” Boris bragged to a reporter, “my ‘serious’ musician friends looked down their noses at me, and said, ‘Boris, you have sold your soul to the devils of Hollywood.’ Now it is different.” It certainly was, though not in the way that they imagined: Boris had sold his soul, or at least part of it, to the devils of Moscow. On top of the demands of his day job and his many extracurricular activities, Boris was living a double life as a Soviet spy. For now, all that involved was sending Zarubin his monthly stipend in Berlin, though Boris wasn’t even very consistent about doing that. He got away with it not only because Soviet intelligence was willing to keep one of its best prospects on a long leash, but because they were still in a state of upheaval. In late 1935, Stalin was in the process of reorganizing his secret police, which would now be called the NKVD, or People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs. During the reorganization, most current operations were suspended and hundreds of active agents were purged.

Boris had been enjoying the benign neglect of his superiors in Soviet intelligence…As Archimedes reported: “By the tone of his voice, I could sense that he was none too pleased by my arrival.”

In fact, Moscow only found out that Boris had relocated to California when Gutzeit read about it in the New York papers. An agent with the code name “Archimedes” was sent to Los Angeles in late November of 1935 to get Boris back on track. When Archimedes, whose real identity has never been determined, called the Paramount switchboard for Boris’s telephone number, he was confused to learn that far from being head of Paramount’s Hollywood studios, Boris was merely its new director of music. The confusion turned to concern when Boris’s secretary rebuffed Archimedes, telling him that Boris was extremely busy and wouldn’t be seeing anyone. When Archimedes telephoned again later that day and received the same response, his concern with Boris’s deception turned to the kind of cold anger that Soviet agents were trained to channel into results. “Rising doubts in my mind forced me to resort to cunning,” he reported back to Moscow. Archimedes telephoned one more time, and assuming an English accent, said he was a Mr. Goldstein from New York with news of Boris’s family back in Russia. The ruse worked. Boris called back within the hour and was surprised to hear a heavy Russian accent on the other line. Boris had been enjoying the benign neglect of his superiors in Soviet intelligence, but he agreed to meet the next day after business hours. As Archimedes reported: “By the tone of his voice, I could sense that he was none too pleased by my arrival.”

The next day at five p.m., Archimedes was waved through Paramount’s imposing front gate. He walked along the studio’s campus, marveling at the costumed actors strolling around Hollywood versions of New York’s Lower East Side, Paris’s Latin Quarter, and a Western ghost town, until he arrived at Boris’s office building. It was certainly a step up from the warren of windowless rooms Boris had occupied back at Paramount’s New York headquarters. Boris gave Archimedes a typical Russian welcome: a bear hug, a glass of vodka, and an inquiry into his visitor’s health, the health of his family, and the health of his friends and colleagues.

Archimedes wanted to get right down to business. Why hadn’t Boris been living up to his promise to write regularly to Zarubin in Berlin? Boris apologized and promised to try to do better. But he balked when Archimedes asked him if it might be possible to put an NKVD agent on the Paramount payroll in Hollywood. Boris claimed that he’d just arrived, and anyway, despite having bragged that he was being made head of the whole operation, Boris now claimed he was a lowly director of an unimportant production division, a job he said was called “minor and administrative.” It didn’t come with the authority to make such decisions, Boris noted. Archimedes kept his cool. He might have confronted Boris about his lie about becoming head of the studio, but he thought twice and decided to save that card for later. In the meantime, he handed Boris a wad of cash and told him to post fifty dollars of it right away to Berlin and to send the rest in monthly installments. Boris exhaled in relief and led Archimedes to the door, assuming that would be the last he’d ever see of him. Boris was surprised when Archimedes told him he’d be back the next day.

By Tuesday, Boris had thought things through and was ready to try a different approach: a better lie. He told Archimedes he might be able to place one or two Soviet operatives on his Hollywood payroll, but he’d have to check personally with New York, and he wasn’t scheduled to go there for months. Boris, of course, could hire whomever he wanted, and was in fact planning a trip in just a few weeks for a series of meetings with Zukor. Archimedes would have been merely annoyed at Boris’s lack of initiative if he hadn’t been shocked to suddenly realize that the door to Boris’s office was wide open. Boris’s secretary, Archimedes saw, could hear every word of their conversation. When he signaled to Boris that he didn’t want her listening in, Boris laughed and asked her to bring him the file of his correspondence with Zarubin in Berlin. As Archimedes reported to Moscow, Boris acted not only with a complete lack of discretion, but actually defended his indiscretion as a strategy. “The more open, the better,” Boris explained. Hiding his contacts with Berlin from his secretary would only cause suspicion.

Archimedes didn’t see it that way. When Gutzeit saw Archimedes’s report in early December 1935, he wrote to Moscow that it was clear that the seduction of Moscow’s man in Hollywood was going to be complicated: “All of F.’s intrigue since his return from the Soviet Union,” Gutzeit wrote, was evidence that Boris “wished to sever ties with us.” Gutzeit wasn’t willing to let go of Boris that easily: “We do not intend to leave him alone. In 2–3 months we will meet with him again and try to get the help he promised.” But Gutzeit was soon too busy trying to survive to keep chasing down Boris, who had made a trip to New York and even flown back with Zukor himself in late January. Boris heard nothing from his new friends for another eighteen months. The delay was largely due to the ongoing purges of counterrevolutionaries and suspected counterrevolutionaries that Stalin had been carrying out since 1934. Gutzeit, Archimedes, and the entire Soviet intelligence service had been living in constant fear, terrorized by the idea that every cable that arrived from Moscow might mean their being recalled and sentenced to death by a single bullet to the head somewhere in the vast basement of the NKVD’s Lubyanka headquarters. And when that maddening insecurity had reached its peak, Stalin decided to purge the purgers in show trials that nominally targeted Trotskyites and Jews, but were often motivated by nothing more than the supreme leader’s paranoia.

It wasn’t until mid-July 1937 that Boris heard again from the NKVD. This time it was Paramount security on the telephone, asking what they wanted him to do with an “Edward Herbert,” who was at the front gate demanding to see Boris right away. Boris, thinking that it was Zarubin, and remembering he’d heard that even some of Moscow’s most venerable agents were being called to account, realized he had no choice but to let him through. As it turned out, it wasn’t Zarubin, but a youthful, dapper figure with an eye patch who introduced himself as Samuel Shumovsky, a diplomatic officer based in Washington, DC, who was on the West Coast to honor a group of Soviet pilots that had just set a distance record, traveling from the Soviet Union over the North Pole to California. As Boris quickly surmised, Shumovsky was in fact a Soviet agent who, under the code name “Blerio,” specialized in gathering intelligence related to aviation technology. Gutzeit had instructed him to make a special trip to Los Angeles to find out why Boris had failed to keep his end of their bargain.

Boris had known on some level that he would eventually have to account for stranding Zarubin in Berlin without enough money or proper cover, which is why his answer was well prepared.

Shumovsky walked through the door of Boris’s suite and, with a glance at the secretary, entered Boris’s office, closed the door, and exploded in anger, cursing and shouting that Boris had put the life of one of Stalin’s most honored spies in danger from the Nazis. Boris had known on some level that he would eventually have to account for stranding Zarubin in Berlin without enough money or proper cover, which is why his answer was well prepared. Boris couldn’t keep his promises to Moscow anymore, he claimed, because Paramount was finally planning to pull out of Germany altogether—which would not in fact happen for years—and keeping people on the payroll there just looked too suspicious. Failing to maintain contacts with Zarubin in Berlin might put one man’s German assignment in danger, but getting caught sending letters and cash every month would put all of Moscow’s American operations in jeopardy, Boris maintained. If Shumovsky appreciated the logic behind Boris’s argument, he seemed convinced beyond any doubt when Boris pulled out his wallet and handed over the hundred dollars that he still hadn’t sent to Berlin. It was a gesture that satisfied and impressed Shumovsky, making an even bigger impression than if Boris had claimed to have sent all the money. Boris might have been slow to understand who his new friends were, but he was learning fast: Communists were often more in thrall to kapital than the most committed capitalist, unable to imagine why anyone would ever voluntarily return money, unless they were either incredibly rich or ideologically committed. Still, Shumovsky left Boris’s office with a warning: You don’t have to send any more money, but you must continue to write to Berlin; the life of the man you know as Edward Herbert depends on it. And so does yours.

Soviet agents had suggested before that Boris was playing a deadly game, but he’d never taken it quite seriously until now. Boris was so terrified by Shumovsky’s threat that he fled. Within a few days, Boris and Catherine boarded a train at Pasadena’s newly opened Mission Revival–style passenger train station, the legendary “Gateway to Hollywood,” and headed east. Boris had sold the trip to Catherine as a surprise vacation that would take them to London, Paris, Vienna, and Leningrad, but she knew better, if for no other reason than that the papers had announced that Paramount was sending Boris to Europe to look for someone for the title role of the new production of Carmen. It wasn’t clear how a visit to the Soviet Union fit into the agenda, but Moscow not was pleased to have one of its most valued American contacts gallivanting across Europe and making plans to visit the Soviet Union without letting them know first. That was the point: Boris was trying to extricate himself from the grip of Soviet intelligence by showing them that he was too indiscreet, too unpredictable, too busy to serve their purposes.