Behind Bond, John le Carré’s creation George Smiley, may be the best known spy of espionage fiction. He is also described as “breathtakingly ordinary.” Perhaps it’s this paradox of intrigue and seeming ordinariness that provokes a compulsion to explore the home lives of spies. We may wonder how far the secrets go, how double the life is, and yet how regular the domestic dramas.

Interest in how the work of a spy might shape his or her ability to build a life at home, to foster connection, and to trust prompted me to write my novel Quotients. I imagined a man who would want to leave behind a life of vigilance to cultivate the comforts of family but find himself compelled back to suspicion. And I imagined that he would find himself in our world today, in which surveillance large and small—from casual social media reconnaissance to mass data harvesting—is impossible to completely elude.

Some of my favorite narratives have turned toward the domestic lives of those who spy. The Wire’s McNulty will never quite make right with the mother of his children, though he will drink in the car. In Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, Alden Pyle’s particular mixture of doggedness and ignorance propels him both to the compromised loyalty of a young woman named Phuong and compromised operations in Vietnam. The following books slip through the threshold of the operative’s home to furnish a sense of the spy as a parent, child, and lover.

Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson

Like The Quiet American, Tree of Smoke offers an agent of some sensitivities. Skip Sands does PsychOps in Vietnam under the cover of a job at Del Monte but also thinks of a killer as “the carrier of a transcendental burden.” Throughout Johnson’s novel, Sands’s family life bobs to the surface of the spy narrative, offering glimpses into the life of a man who once was a kid getting confirmed in a Boston church, whose uncle is a colonel, and who grew up without a dad. Sands’s burden is not only his involvement with the CIA but a legacy of violence.

Woke Up Lonely by Fiona Maazel

Maazel’s signature punchy tenderness is as singular as the scope of her ambitious novels. Woke Up Lonely centers around an intelligence agent, Esme Haas, who becomes entangled in a hostage crisis after her ne’er-do-well ex, Thurlow Dan, accepts money from North Korea. Thurlow’s naïveté and Esme’s canniness meet on a scale of global intrigue, representing twin pitfalls in a lonely world.

My Father, The Spy: An Investigative Memoir by John K. Richardson

Richardson’s memoir tracks his pursuit of knowledge about his father, John. Sr. John Sr.’s story is one of high-octane CIA operations around the globe, martinis, and flirting, but it is also one of a man prone to intermittent depressions and one of a father maddeningly distant, exacting, and intelligent, the kind of guy who in a letter about a love affair addressed to his son writes: “She was a baroness, married, two young children. Her husband was an Italian Fascist officer and a prisoner of war in North Africa. Thinking of her and of my years in Italy, I can say that Italy and Italian women contributed considerably to whatever civilization I’ve acquired. For more on this theme see George Santayana’s one and only novel entitled The Last Puritan.” This memoir is an act of tremendous generosity, a document of a son seeking an understanding of an elusive parent.

Democracy by Joan Didion

“Someone who kept the ‘usual balls in the air.’

Someone who did ‘a little business here and there.’

Someone who did what he could.”

Such is Joan Didion’s description of her CIA protagonist Jack Lovett describing himself. But in her elliptical fashion, the detail of his character that she returns to, the detail that becomes the detail perhaps, is Jack Lovett waiting for Inez Victor by Black Point. He’s a gruff romantic, but a romantic nonetheless, stuck in the memory of the narrator as a man waiting for a woman who he remembers wearing flowers in her hair.

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

This witty Pulitzer Prize-winning novel transforms the spy narrative into a metaphor for the liminal space occupied by Asian emigres to America. In Nguyen’s hands, the subversive’s double identity and double consciousness crack apart an image of compliant assimilation, opening up a stage for roguish social critique and reflection on the absurdities of war. One of the greatest pleasures of The Sympathizer, however, are the scenes of hard-nosed repartee between the narrator and his lover. Addressing her as Ms. Mori, he declares, “I think I’m falling in love with you.” To which she replies, “It’s Sophia.”

American Spy by Lauren Wilkinson

American Spy is the only spy novel I can think of framed as a letter from a mother to her children, and this structure affords its narrator, Marie, the room to muse on how she has entered into a profession which requires her to deposit her children knowing she may not see them again. This structure allows a thrilling plot to be edged with grace. Alternating between stories of her upbringing and her career, Marie’s narrative is as much about a woman reckoning with the way in which she’s become the kind of mother she hoped never to be as it is about passing through Quantico.

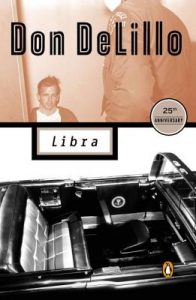

Libra by Don DeLillo

Any true Don DeLillo fan will recall the beautiful kitchen scene of Win Everett eating breakfast in his middle American home, buttering toast and making the gesture he makes when he may have cut his wife off or said the wrong thing. In DeLillo’s hands, the CIA outcast is not pretending to be gentle with his wife and daughter. Everett is a man whose thoughts leak past their contexts, who even as he suggests a plot to bungle a presidential assassination worries aloud that his daughter ought to keep more secrets.