This isn’t exactly the hottest take you’ll come across today…but crime is bad. Even experiencing a minor crime is pretty terrible. But that doesn’t mean you can’t have fun with it!

No wait, I said that wrong. That sucks. Sorry. Let me start over.

So much of crime fiction can be a grim wasteland of humorless men hellbent on spilling blood, and we should…

Okay, I just reread that sentence, and that actually sounds like a kickass movie, probably starring someone like Jon Bernthal, and now I want to see it.

What I’m trying to say is that, although crime and violence are often horrific, and writers have a duty to convey that seriousness, there’s an importance to letting the occasional light moment shine. I’m always impressed with the writers who manage to do that well, and there are few better than Carl Hiaasen.

In Skinny Dip, one of my favorite Hiaasen novels, the protagonist Chaz Perrone is a shady marine biologist who is helping a business destroy the Everglades. When he suspects his wife of realizing his plans, he pushes her off a cruise ship. But she ends up being saved by a handsome stranger and decides, with the help of that stranger, to derail Chaz’s plans.

Much of what defines a classic comic crime novel is here. The destruction of the Everglades ties Hiaasen’s novel to the great traditions of crime fiction, ground that has been walked by Chandler and Hammett and more, which is the lone wolf or underdog against larger societal structures, often the political or financial establishment (or both).

And there’s dark humor in Chaz throwing his wife overboard. Not that spousal murder is comic gold, but, look – there are far grimmer ways he could have killed his wife. That humor and tone is continued and enhanced with Chaz as a bumbling criminal, one of the more successful tropes in crime fiction, particularly comic crime fiction. We know Chaz is dangerous because he tried to kill his wife, so the danger is there and true and, if he gets his act together, his wife is in real peril. But there’s going to be humor, along with the potential of romance, both which keep the darker elements of the novel at a distance.

Kellye Garrett’s celebrated debut novel, Hollywood Homicide, is one of my favorite blends of comedy and crime. Her protagonist, Dayna Anderson is a down-on-her-luck, out-of-work actress who, as the story opens, is interviewing for a job at a restaurant whose slogan is “Ask Us About Our Large Jugs.” The very first two lines of the novel are:

He stared at my resume like it was an SAT question. One of the hard ones where you just bubbled in C and kept it moving.

The comment about tough questions on the SAT, which answers you skip, lets us know that Dayna’s not some borderline genius, but she’s aware of that. And she can laugh about it. That self-awareness is hugely important, because it also tells us that Dayna is going to tread the line between self-deprecation and mockery, which immediately defines our expectations of humor.

Another great moment, that reflects the immediacy of introducing humor and how it can expertly establish character, happens when Dayna describes Joey, the man with whom she’s interviewing. She notes that he probably doesn’t have “a centimeter of hair anywhere on his body.” And, immediately, she makes a mental note to “ask him about his waxer.” In addition to comedy, this gives us quick insight into Dayna, about what she sees as important. She’s a little on the shallow side (maybe more than a little), sarcastic, and interested in looking good. But that’s presented comically, so it’s not off-putting to the reader. That’s an incredibly difficult tightrope to walk, one Garrett nimbly skips across.

Those first examples are from a comic novel and cozy, both which lend themselves to humor. But Lou Berney used comedy to wonderful effect in this year’s fantastic Dark Ride. Berney’s latest thriller opens with an ambitionless stoner who, while paying a traffic ticket, sees two small children with cigarette burns dotting their bodies, and the sight relentlessly haunts him until he’s driven to help.

Which, no, doesn’t sound funny, but that’s part of what makes Berney—like Garrett and Hiaasen—one of today’s best, most compelling writers. Berney’s protagonist, Hardly, is warm-hearted and likeable and deceptively complex, but he’s also aware (and, initially, welcoming) of the stagnation in his life. This is brilliantly reflected in the reactions of the people he draws to his cause. Like the young goth attendant at Driver Verification, when Hardly tells her he’s decided to help those children:

“You?” she says. “You are going to investigate and look for evidence? That is the most delightfully hilarious thing I’ve heard in ages.”

I’m not offended. Believe me, I’m just as dubious about my qualifications as she is.

Like Garrett, Berney employs sarcasm for his humor, but note the difference in how they apply sarcasm, compared to the mean-spiritedness that type of humor often implies. There’s a warmth in it, a self-effacement that lessens the vitriol.

As a writer and reader, I’m drawn to that warmth. I employ and seek it because, when writing and reading about crime, we’re often (as much as the victims are) looking for answers. Without it, the palate of colors doesn’t seem quite as vibrant. As one of my favorite musicians said, when talking about how trauma informed his early work, “I didn’t yet know that the easiest colors to paint with are the darker colors.”

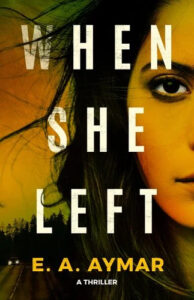

As someone naturally drawn to dark colors (for real, all my tattoos are black and gray), I’ve found moments of humor utterly necessary in my work. When creating the character of Lucky Wilson, a hitman who is one of the protagonists of When She Left, I realized the conflict in him was the pull to his family and the allegiance to his work. And I decided to lean into that, and gave him a love for all things Christmas. That added layers to Lucky and the novel I hadn’t yet realized.

And it made the harder, evil elements of the novel somewhat easier to write. We need the warmth. There has to be somewhere for readers to turn when it’s cold.

***