Punk and crime go together like boots and broken glass, 53rd and 3rd, Sid and Nancy. Since the first squall of feedback ripped through an amplifier, punk rock has been associated with criminal activity.

Punk emerged as an art movement—yes an art movement—that manifested as a disorganized, reactionary, uncouth urge to pick up musical instruments and make some noise. Bands played in shitty clubs and shittier practice spaces in cities hit hard by unemployment, inflation, and the white flight to the suburbs across America and the UK.

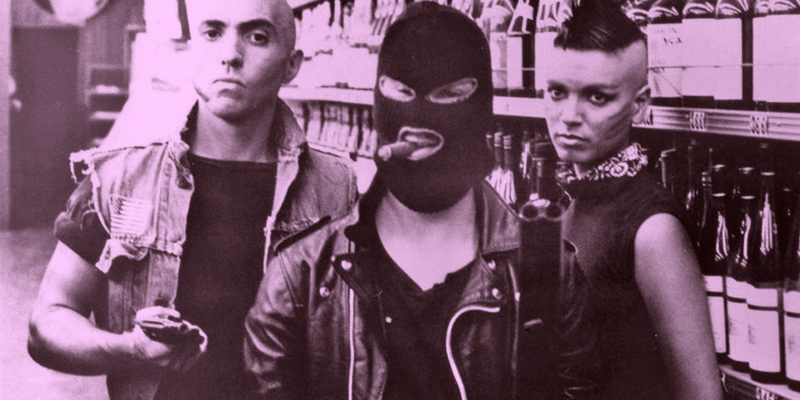

Kids drawn to this spectacle wore leather jackets, extravagant make-up, spiked-up hair, and homemade outfits that served as a form of self-expression that antagonized the squares and warned would-be predators away as they ventured out to decrepit downtown spaces and made them their own.

These punks engaged in the kind of petty crime linked to the pursuit of sex and drugs that are hallmarks of the rock and roll experience, but conservative media outlets missed the memo and treated them like street gangs. They warned their audiences of the perils of punk rock as if it were a virus, which in a sense it was, because when kids went punk, there was no turning back.

By the time the movement migrated to California the association had been made: punk rockers were criminals. LA cops viewed the first wave of west coast punks as part of the criminal underclass of substance abusers, sex workers, and queers. The police indiscriminately shut down shows and beat patrons with their batons for sport.

Keith Morris of Black Flag and the Circle Jerks, Bill Stevenson of the Descendents, Joe Nolte of the Last, and the artist Raymond Pettibon have all told me stories about being on the receiving end of police violence.

The music was faster, stronger, and more violent—and according to the media so were its fans. It’s true many of the new hardcore kids were surfers and skaters and tended to be more athletic, but much of the violence was exaggerated. An LA Times journalist even went so far as to invent the term “the slam” to describe the kind of dancing that went on at punk clubs. The term was ridiculed but caught on nonetheless.

Violence at punk shows became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The media harped on it so much that the stories succeeded in attracting violent people to shows. People who weren’t interested in the music were now showing up at gigs to crack skulls.

Now when the cops came to shut down a show instead of dealing with a few dozen drugged-out art school dropouts, there were hundreds—sometimes thousands—of kids in the audience and many of them were willing to fight back. This escalated the LAPD’s war on punk.

As I wrote in my book Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, bands like Black Flag were routinely banned from clubs and harassed by the police. When they managed to book a gig, inexperienced and unscrupulous promoters cashed in on hardcore’s popularity by overselling the show, all but ensuring the police would come and shut it down. This often resulted in clashes between cops and pissed off kids, which was then glamorized by the media.

Yes, there was violence between punk factions and plenty of vandalism, mainly because shows lacked security and were held in places that either didn’t know better or didn’t care. Television shows rounded up punks for roundtable discussions about violence. There was even a support groups for parents of kids who’d turned punk, as if their children were fruit that had gone irredeemably bad.

By the summer of 1984 the LA punk scene had all but fallen apart. Punk gangs were causing so much mayhem that clubs closed its doors to punk and fans stayed home. LA was hosting the Olympics and the LAPD acted more like an occupying army than a police force. Hardcore bands had no choice but to hit the road.

That’s when things start to get interesting because in early 1984 Repo Man hit theaters. Repo Man wasn’t the first film to feature punks—far from it—nor was it the first film with a punk soundtrack, but it made the biggest splash. It was a mainstream movie with an indie vibe and while it didn’t play in theaters for long it was among the first group of movies to become cult classics by virtue of videocassette. (Interestingly, its soundtrack was released on vinyl just before CDs nearly made LPs obsolete.)

Repo Man is smart, funny, and violent. It doesn’t satirize punk so much as take aim at the way punks were portrayed on American television as cartoonishly dumb. Emilio Estevez is far from convincing as a punk rocker named Otto and Harry Dean Stanton plays an aging, coked-out repo man, but it’s Otto’s former punk rock friends who make the movie so entertaining.

In scores of movies and television shows punks were depicted as lamebrained criminals and low-level thugs: the type the hero (or villain) easily dispatches because, well, they’re punks. They’re not a credible threat because if they were they’d be something else.

Repo Man is different. It glamorizes punk and its relationship to crime. The line, “Let’s go eat sushi and not pay” registers as a joke that is more punk than the version of punk it appears to lampoon.

After Repo Man, punks were everywhere both IRL and in pop culture. Some of these portrayals were nuanced, but most were not. They’re all lovingly cataloged in Zack Carlson and Bryan Connolly’s wonderful Destroy All Movies!!!: The Complete Guide to Punks on Film. This illustrated encyclopedia covers everything from B-movie exploitation films to documentaries like Another State of Mind. Punks were appearing in so many movies there were talent agencies devoted exclusively to providing casting agents with punks for small roles or extras.

For many kids stuck in small towns the punks in Repo Man were weirdly aspirational. Penelope Spheeris’s The Decline of Western Civilization was a better guide to LA’s sputtering scene, but Repo Man was cool. As Gene Siskel pointed out in his review of the movie, Harry Dean Stanton’s “Repo Code” were words to live by. Repo Man’s unusual impact on pop culture is embodied by the fact that the actor who plays Otto’s nemesis would go on to play bass for the Circle Jerks—one of the bands featured in the soundtrack. Even more surprising? Almost forty years later he’s still got the gig.

Inevitably, punk crime has moved from the screen to the page. As punk rock grew in popularity thanks to bands like Bad Religion, Offspring, Rancid, Green Day and Blink 82, punk crime morphed to the white collar variety with disputes between artists and labels over rights and royalties settled in courtrooms. Now that many members of the original punk scene have started writing their memoirs, they are exploring the old days when having blue hair was an invitation to an ass beating and illegal activity was unavoidable.

From stories of childhood abuse to epic drug consumption, these punk scribes aren’t holding back. The unexpected success of NOFX: The Hepatitis Bathtub and Other Stories by NOFX and Jeff Alulis, which is even gnarlier than its title, has opened the door for all kind of explorations of the intersection of punk and crime.

For instance, Patrick O’Neil, a former roadie and road manager for the Dead Kennedys, TSOL, Flipper and the Subhumans has written a pair of memoirs: Anarchy at the Circle K, which is about his life on the road with punk rock and Gun, Needle, Spoon, a harrowing tale about his days as a junkie bank robber that led to being incarcerated in San Quentin.

Novelists are getting in on the act too. S.W. Lauden wrote a series of books for Rare Bird about a punk rock private investigator and Kyle Decker goes the historical route with a new crime novel called This Rancid Mill from PM Press that features a punk private eye in LA during the early ‘80s.

One of the most compelling LA crime novels of 2023 was written by Daniel Weizmann, who wrote for punk zines in the early ’80s under the pen name Shredder while he was still in high school. His novel, The Last Songbird, never mentions the word punk, but crucial scenes are set in Hermosa Beach, the birthplace of Black Flag, and there are some Easter eggs for those in the know.

Whether it’s at the club, on the screen, or between the covers of a book, wherever punk rockers are getting together you can bet they’ll be up to do some crimes.

***