On April 13, 1922, two homemade bombs exploded in a tenement on Eldridge Street, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, destroying the building’s top half and rousing the sleeping neighborhood into panic. Less than two years after the devestating Wall Street bombing, the city was on alert for any sign of anarchist insurrection. Rather predictably, the police arrested a pair of Italians, Gasparo Latiano and Rosario Ficili, accusing them of attempting to kill one of the tenement residents as part of an unspecified vendetta. It does not appear that they were ever formally charged.

I’ve been transfixed by this forgotten piece of New York history since first stumbling on it over a decade ago. I was struck by the stark horror of the New York Times report, which runs just 350 words and includes details of plummeting staircases and flying chunks of plaster that left the residents “with bodies and faces bruised and cut and with bleeding feet.” It’s a mesmerizing piece of storytelling with absolutely no historical significance, and it captures something essential about writing historical fiction: the research is my favorite part.

My fascination with news archives began when I was a child, when my father first took me to the microfilm section of the local library to read the paper from the day I was born: August 27, 1987. Alongside sleek fashion advertisements showcasing fierce haircuts and massive shoulder pads, I saw items about the Democratic primaries, nuclear disarmament, and right wing attempts to ban “humanist school books” from Georgia’s public schools. I was mesmerized by this window into the past. I’ve been reading old newspapers ever since.

The 1922 tenement bombing inspired me to write a radio play, an adventure serial about bootleggers and anarchists in Prohibition-era New York. I spent months wading through the archives, compiling articles about gunfights in the streets, a bomb maker blown up by his own explosives, and a corset shop that was being used as a front for rumrunners. Attempting to hack together a narrative using all of this wild material, I failed miserably, but I didn’t care. Reading those articles was reward enough.

Beginning writers are warned not to overdo it with their research. Too much detail can overwhelm a narrative, they are told. Too much reading can sap your enthusiasm to write. These pitfalls are real, but for those writing anything not directly based on their own life, research is essential. Done properly, it can be a pleasure—the rare element of writing where failure is impossible, where the process can simply be enjoyed. To that end, I’ve knocked together four rules for historical fiction that will make it hardly feel like work at all.

Start With a Plan

Unless your topic is exceptionally obscure, when you begin your research you will probably find an overwhelming amount of material. (If you are writing about something truly obscure, lucky you! Just make up whatever you need.) Before emptying the shelf at the local library, plan your attack. Choose two or three sources and pick them dry. It’s likely they will give you everything you need.

I also recommend setting a specific length for your research period, perhaps while you are finishing something else. Learn everything you can in six weeks and move on. You will have plenty to start.

Read Weird Books

The more specific your sources, the happier you will be. If you’re writing about New York in the 1890s, a survey history of the Gilded Age will only get you so far. Far better to spend your time digging through the archives of the Police Gazette, the era’s foremost tabloid, where in a two page spread you’ll find stories of rat fighting, women factory workers brawling with strikebreakers, and Professor John Whitman, who could lift 225 pounds with his teeth.

Period newspapers, books, and magazines are essential—not just for the characters they present, but because they show what people of the era cared about. Old guidebooks and maps are also invaluable—I keep the 1939 WPA Guide to New York beside my desk at all times. The most valuable thing you can take from your research is not raw facts, but the vibe of the time and place. Once you absorb that, your stories will come alive.

If You Get Bored, Quit

In Act One, Moss Hart writes that, “It is sometimes far better for a writer to allow a lively imagination to roam over the field he has chosen than to research that field within an inch of its life,” suggesting that it’s only necessary to know a bit more than the audience in order to secure their trust.

With historical fiction, I think it’s necessary to go slightly farther than that—our readers are more likely to fact check than a Broadway crowd of 1930—but there is no reason to go past the point of fun. Remember that you’re writing a story, not a research paper. Not only do you not need to learn everything, you probably shouldn’t. It will only weigh you down.

Don’t Use It All

I have never been a Hemingway fanboy, but I agree with him on two key points. The first is that daiquiris are underrated. The second is that he was right when he wrote, in Death in the Afternoon, that “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them.”

In doing research, your job is to fill yourself with as much knowledge about the topic as interests you. This will allow you to write with confidence—the most important tool a writer can have. The reader will respond.

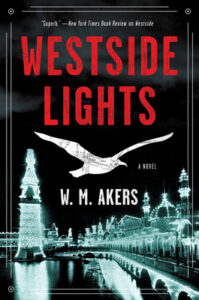

Unused material is never wasted. Even after my radio play imploded, I never stopped hanging out in newspaper archives. When I wrote my debut novel Westside—whose latest sequel, Westside Lights, comes out on March 8—the bootlegging corset saleswoman featured prominently. And the exploding Eldridge Street tenement bounced around my head for a decade before I used it to inaugurate my newsletter, Strange Times, which documents the weirdest news ever printed in the 1920s New York Times.

Even if I’d never done anything with it, I’d have been glad to hear the tale. I love a good story—true or false, useful or not. I will never get enough.

***