I have always been fascinated with creatures, and I have wished to invite them into my life for as long as I can think—ill-fated early attempts at trying to hatch chicks from un-incubated eggs and breeding racing snails can attest to that.

But while chicks are cute and racing snails are ambitious, there was one companion I coveted more than any other: I cannot remember a time when I didn’t want a dog.

Unfortunately, my parents were a sensible lot, and so I spent a large portion of my childhood being bribed with low-maintenance hamsters and fobbed off with annoyingly reasonable arguments. Who is going to walk him? Who is going to train him? Who is going to clean up after him?

I! I! And yet again, I!

By the time I had finally achieved freedom from parental rules, some of their arguments had managed to seep into my own mindset. Of course, taking in a dog is a huge responsibly. Of course, they require not only love, but time, training, walks and ideally a garden. Of course, you can’t expect them to sit at home all day waiting for your return from uni.

I spent my student years responsible and dogless. Time passed.

Life unfolded.

One sunny day I found myself an author, living in the verdant English countryside, in possession of a house.

I was working from home. I had a garden. Surely, now, if ever, was the time to invite a waggy, sharp-toothed muse into my life! I could already picture myself typing away on my computer, my faithful hound snoozing at my feet.

I can honestly say that the day I brought home my first dog, Fyodor, an impossibly soft pup the colour of smoke, was one of the happiest in my life.

The subsequent night, however, turned out to be an entirely different story. Just how many times could a tiny puppy need to go out in a single night? I didn’t sleep a wink. The next morning found me bleary eyed and the pup exuberant, ready to dig his needle teeth into anything that moved—and quite a few things that didn’t. I couldn’t even glance at my computer, let alone work on my novel.

Overnight, I had turned from author-with-a-deadline to full-time dog-police. Don’t bite! Don’t chew! Don’t dig! Don’t bark! And above all: Do not pee on the blasted kitchen floor!

This was hell!

How was I supposed to think? How was I supposed to write?

The truth is: a puppy is the very opposite of a muse. They don’t inspire—they distract, absorb every last little stray bit of your attention and energy.

*

One of the things that kept me going during these taxing first months was the odd stolen glance at other authors. Being a dog owner and being a writer were not mutually exclusive. Others before me had brought pen to paper in the presence of a canine, hadn’t they? World literature is full of dogs, described in touching and accurate ways that show their creators had some firsthand experience in the matter.

There is Argos, Odysseus’ faithful old hound, recognizing his master when no one else does (and tragically suffering a heart attack in the process). There’s Jack London’s White Fang, Virginia Woolf’s cocker spaniel Flush—all splendid fusions of fiction and dogginess.

Apparently, the top dog in Virgina Woolf’s own life was her mongrel Grizzle. He even makes a surprise appearance in her diaries: “As for the soul . . . the truth is, one can’t write directly about the soul. Looked at, it vanishes; but look [. . .] at Grizzle, [. . .] and the soul slips in.”

Yes! Obviously, I was neither Homer nor London nor Virginia Woolf, just a writer of mystery stories, but this was what I was ambitiously hoping for: a slippery shard of soul!

Naturally, over time, things improved on the domestic front. There still were days when I couldn’t write, but there was never a day when I didn’t laugh, didn’t feel my existence was richer and more complex than before. Our lives fell in step and trot and what had started out as outright canine sabotage, slowly morphed into something best described as a gentle and rather random inspiration. It seemed like a miracle at the time, but of course there were good reasons.

A lot of my writing has always been about exploring the world from different angles, and few things help you shift your point of view like looking after a dog. Their world is fundamentally different from ours, full of scents and sound and speed and big big feelings. Understanding this world is crucial for interspecies bliss—in short, I was treated to the crash course in empathy I didn’t think I needed.

A dog in the house will also help you to put things in perspective, recalibrate your sense of self-importance as a writer (and a human being). Nobody in your home is going to care more about you than your dog. And absolutely nobody is going to care less about your literary achievements. A book is a chew toy in the making, that is all.

To me, this approach is quite refreshing and by no means trivial. I have always felt that writing a novel is in part a disappearing act. The goal is to become transparent as an author, allowing the reader the best possible view of the story beyond. It is not about you—it is about the world. I can attest that Fyodor helped me quite a bit to hone this transparency.

Looking back, it almost surprises me to see how many dogs have found their way into my books. There has never been a dedicated canine protagonist—maybe because this feels too close to home and dangerously non-fictional. But the dogs on the sidelines matter.

There is Tess, George’s old sheep in Three Bags Full. She barely makes an appearance, but her absence speaks all the louder.

Brexit, the wolfhound in the Agnes Sharp series, is a chaotic and reassuring presence in the house share, providing my senior detectives with warmth, protection and dog hairs alike.

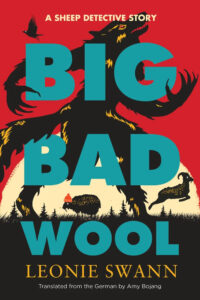

Yet, the highest density of dogs is found in Big Bad Wool, my second sheep detective story. The situation is tense. My sheep protagonists are facing a series of mysterious killings and need all the help they can get. We finally get to spend some time with Tess; a lonely, heart-wrenching howling foreshadows dark things to come and Vidocq, the Hungarian livestock-guardian dog comes to the rescue. Even the perpetrator might or might not be a canine of sorts.

*

None of these stories are about the dogs, and yet the books are richer for them. Maybe their presence does imbue the works with a soul.

There is a flipside to all of this, of course: the utter lack of inspiration that follows the death of your dog. When Fyodor died shockingly young, I was lost, devastated, desperate for the feeling of a wet nose nuzzling into my hand. Nothing worthwhile was written for over half a year.

The pain was just stunning. Was it worth it?

Yes. Without any question.

I am writing these lines with my dog Ezra snoozing at my feet—and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

***