In the late eighties, it was dirty, run down, and trashy. And we loved it.

Back then, my future husband and I started making road trips to the desert, bearing witness to the last remnants of Old Vegas. This was three decades before I ever even dreamed I would write a novel about the beginnings of Las Vegas and a time when Sin City was haunted by mobsters, entertainers, and occasionally, my grandparents. We were driving to Vegas the same way the World War II vets and their wives drove there, the same way my grandparents drove there, having dropped my mother off at a Baltimore orphanage, never to see her again, and headed west—windows rolled down, heading for the pools and air-conditioned rooms of the garden motels in the Paradise Valley desert. Ready for fun. Five hours of this and then we’d see the great neon glow ahead in the night.

The Strip.

We thought it was magnificent, even though Vegas was in full plummet then, old hotels barely hanging on, not yet imploded and replaced. They had been updated, hurriedly and unbeautifully, slapped up with new towers of rooms (now that garden style motels were no longer in vogue), new entrances, new signage. All the majestic old signage sits in The Boneyard, on the grounds of the Las Vegas Neon Museum, a great outdoor lot, pale, lost giants devoid of the hotels they once clung to.

Vegas was in full plummet then, old hotels barely hanging on, not yet imploded and replaced.New laws allowed corporations to own casinos, and these corporations were discovering to their delight, just as the mob had, exactly how much money was in gambling. A fortune. And these corporate owned casinos abruptly began recording record profits because, unlike the mob, they accurately reported their earnings to the U.S. government. The mob always kept two sets of books, one for the government and one for Meyer Lansky, paying taxes on the one and shipping the skim to the other for distribution to the syndicate all over the country, millions and millions of dollars every month. In addition to casino profits, drug money from Lansky’s heroin networks were laundered through Vegas. And as if that weren’t enough, casinos owners would stick up their own armored trucks filled with money, then keep the money and collect losses from their insurance companies. Once the government became aware of just how much money the mob had been skimming from every casino, it redoubled its efforts to remove mobsters and racketeers from Vegas under RICO. And so we arrived in a Vegas in transition from mobsters to corporations, before the new hotels, before Vegas became trendy again. The only way Vegas could compete before it reinvented itself was by offering cheap rooms, cheap food, and loose slots.

Offers from which we benefited.

We stayed at plenty of those old, cheap hotels—the Tropicana, the Dunes, the Desert Inn, the Flamingo, the Imperial Palace, the Stardust. Almost all our rooms were weird, shabby, plain, misshapen things. At the Flamingo, our room was so tiny, so ordinary—two twin beds and a mid-century lamp on a nightstand between them—it reminded me of the bedroom I shared with my sister when we were little girls. At forty dollars it was a bargain. One hotel room at the Stardust had a long narrow hallway stretching from the bedroom to the bathroom, a hallway so poorly lit that the maids couldn’t see the previous guest had somehow lost her underpants on the way to the toilet, a black and slinky pair over which I tripped on my own way down that hall. God knows what I left behind. In yet another hotel room, we found a half-empty bottle of Astroglide on the carpet by the bed.

At our one and only stay at the Polynesian, we walked through a lobby so cavernous I thought we’d never reach the front desk. The casino hadn’t yet acquired its gaming license, but the space was reserved for the tables and slot machines that would someday arrive. New gleaming lobby furniture winked at us as we followed the bellhop to check into our thirty dollar a night room. This was going to be great! And then we opened the door to our hotel room, and we gradually understood that nothing here was great, that all the furniture was nicked, battered, and old, bought up from older hotels, from those 1950s rooms, bought on the cheap and stuffed in here. The pool’s swim up bar was closed and looked as if it had been for years. In the 115 degree heat we sat, crestfallen, in the center of the pool, on the submerged stools at the shuttered counter. Thirty years later, we still say to each other when something looks great, promises a lot, but actually turns out, to our slow, unhappy realization, to be a shit show, that it’s the Polynesian.

But we were newly adult then, just barely legal, so we didn’t care if the furniture was battered or the carpet unclean or the pool bar closed. We were having an adult adventure, an affordable adult adventure, which was what Las Vegas used to promise: affordability. Cheap and affordable were marquee words back then: every hotel bragged about its rock bottom prices–rooms for twenty dollars, 99 cent shrimp cocktails and free drinks, the midnight steak and eggs buffet for $2.99. And all the hotel marquees bleated, as well, that their casinos hosted the loosest slots in town, 98.9 percent return. Or maybe it was 99.9.

There was no bedtime. There was just sex, alcohol, gambling.It was the upside down. What was usually expensive, was cheap. What was usually bad, was good. There was no bedtime. There was just sex, alcohol, gambling. And it was fascinating.

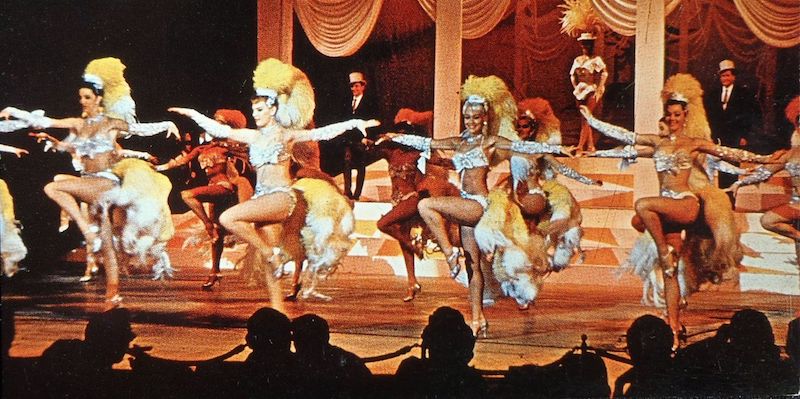

Showgirls strutted topless, men drank themselves sick for free as long as they sat by a one-armed bandit, and young men stood on the Strip openly handing out business cards that advertised men and women available to rent as escorts. Back then, big wads of money were transmogrified into chips of wax and clay and paper. (At the casinos no one blinked at a hundred dollar bill. A hundred dollar bill was like a dollar bill.) You went to the cage with your bills, got your quarters, played them all night. Now you play with a slip of paper you insert into a machine, which reads the dollar amount, and if you win, a piece of paper slides out of the slot like the tongue of a snake, telling you your profit.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Las Vegas with its smaller hotels reflected the modesty of post-war America—the small suburban houses with a single car in the garage were echoed in the scaled down Vegas casinos with just a few tables and with hotel rooms that were simple, almost spartan—like the ones at the Flamingo. During the late 1950s, the garden motels added towers of rooms, and in the late sixties, Caesar’s, the first modern multi-tower hotel was built. By the 1980s, as Hilton and Kerkorian and Adelson and Wynn and their corporations discovered just how much money could be made from gambling, they understood they could compete with the Indian reservations and Atlantic City only by building huge theme park hotels. And so, at the end of that decade, they began rebuilding Vegas, imploding the old and constructing the new. An operation that continues still. Now, even the most ordinary room at Sheldon Adelson’s Palazzo is a suite, with a sunken living room, a light up bar, a marble bathroom, and three televisions—an echo of the suburban McMansions being built in the rest of the country. Alongside the ever-increasing size of the hotel rooms are the ever-increasing sizes of the hotel casinos. You need a wheelchair to get from one end of Caesar’s to another. You need a car. And you need a credit card. Nothing is cheap in Vegas now.

The old mobsters like Moe Dalitz who’d been in Vegas since 1950 thought new corporate owners like Steve Wynn wouldn’t be in Vegas long.

Ha.

I was there to see the last bits, the remnants, the bones behind the flesh, of old Las Vegas, before its hysterical, bloated reinvention.The intimacy of Ben Siegel’s 1946 Flamingo Club, which I write about in my novel is gone. For good. I was there to see the last bits, the remnants, the bones behind the flesh, of old Las Vegas, before its hysterical, bloated reinvention. I loved that the Sky Room at the Desert Inn created atomic cocktails in homage to the nuclear testing, that the pool had a nighttime water, light, and organ music show, that the musicians gathered in the parking lot of Chuck’s House of Spirits to drink and unwind after two gigs at the hotel showrooms, that the staff at the Flamingo whooped it up after their shifts at a shack called the Flamingo Annex. And maybe that’s why I wanted to write about it all, to revivify the 1950s Las Vegas still just visible then beneath the towers added to the old garden style motels, beneath the new neon and the new behemoth casinos.

And I also wanted to revivify my grandparents, whom I never met, and to imagine the life my mother might have lived with them if they had taken her along on their wild ride west. She’s never set foot in Vegas. On principle. But she’s there in my novel. She stands with her father and Bugsy Siegel on the early site of the Flamingo Club before anything was there but a crumbling old motel, feeds the feral cats that roamed the grounds for years, works as a cigarette girl on the disastrous opening night, auditions for Donn Arden who created the first floorshow for the Painted Desert Room at the Desert Inn.

She weeps when Ben Siegel is killed. She, not a cocktail waitress, serves mobster Tony Cornero the poisoned drink that kills him while he’s playing craps in the early morning hours at the Desert Inn. He wouldn’t give up the Stardust to the bigger mobsters who wanted it. She rubs shoulders with Meyer Lansky and Moe Sedway and Davie Berman. She’s standing in costume when she hears Gus Greenbaum was murdered. He wouldn’t give up his share of the Riviera, so he was nearly decapitated, in bed, while watching television, his wife’s throat cut while she lay, hog-tied, bleeding on her own living room sofa.

My mother haunts the stages, the casinos, the pawnshops, the short-lived racetrack, the hills of the Las Vegas Wash. She moves into the first suburban tract built near the Strip by Moe Dalitz and Irwin Molasky—Paradise Palms. By the end of the novel, she’s a headliner at the Stardust, and shortly thereafter she suffers a reversal of fortune and loses everything.

Because that’s Vegas.

My grandparents’ Vegas.

They died in Medicaid nursing homes. Penniless.

Las Vegas. My muse.

I have a guest soap from the Desert Inn on my writing desk. The hotel was imploded almost twenty years ago but the soap still has a scent.

On my last trip a few years ago, for old times’ sake, we played the poker machines at Slots A Fun, an artifact from the early seventies and the only place left on the Strip advertising loose slots. With its open front, dollar beer, and free popcorn, the place looked more like a carport or a carnival stand than a casino, so run down now we shared the space with a homeless woman carrying her garbage bags and muttering to herself, but we won money. Like the old days. I haven’t won a dollar in Vegas in two decades. Then we spent New Year’s Eve standing out on the Strip, police everywhere, SWAT snipers on the roofs of the hotels alongside the fireworks all set up to go. Post 9-11 Las Vegas. And next to me, a young man in a hoodie called out enthusiastically as each hotel—Aria, Caesars, MGM Grand, the Stratosphere, the Venetian—shot off their great fireworks display, “Man, this city is the tits!”

No, baby.

Used to be.