Let me confess something right off the bat: I love “Cast of Characters” lists. You know, those abbreviated descriptions of dramatis personae that so frequently appear at the beginning of old novels.

At their best, such roll calls serve two functions: they help readers to keep straight the identities of multiple individual performers and their relationships with others in the story; and they supply some distinctive entertainment of their own. Those portrayals of personages waiting impatiently to take the stage might range from the portentous (“Chief Turner—His integrity didn’t interfere with his ambition.” The Last Score by Ellery Queen, Dell, 1964) and the evocative (“Prince Kuriacha—The bow-legged, gorilla-bodied wrestling champ looked about as peaceful as a Tartar tribesman, even in his Brooks Brothers suit…” The Girl’s Number Doesn’t Answer by Talmage Powell, Pocket, 1960), to the puzzling (“Dr. Samuel Benning—worried, balding, small-town doctor whose wife is his only disease.” The Ivory Grin by Ross Macdonald, Pocket, 1967) and the downright comical (“Judge Brooks Randall—somewhere in his sixties, is a lean, ascetic-looking man with polished pewter hair and a pair of eyes that go with a 60-day sentence for contempt of court.” The Crooking Finger by Cleve Adams, Dell, 1946).

“Cast of Characters” pages date back at least to the 19th century and such densely populated yarns as Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1853), which limned one of literature’s early eccentric sleuths thus: “Mr. Inspector Bucket, a sagacious, indefatigable detective officer.” Yet they enjoyed a particular and particularly creative later flowering during the mid-20th-century American paperback boom. It became de rigueur back then for crime-fiction publishers such as Pocket, Dell, Ace, and Permabooks to open their releases with rosters of this sort. (Those might disappear from subsequent versions, however, which is why I mention the publication year of each vintage edition cited here.) Some lists included not only provocative or revealing personality details, but also the page numbers on which the players were set to enter the plot line. The choicest examples were pawky and piquant in comparable measure; they were intended to bring a smile to the reader’s face and perhaps even mine a chuckle from his or her throat.

Consider, for instance, the following introduction of the protagonist in Dell’s 1947 “mapback” edition of C.W. Grafton’s The Rat Began to Gnaw the Rope: “Gil Henry—short and pudgy and lives at the YMCA, is a very junior partner in a big law firm. He had more curiosity than an old maid, his mind is so sharp it nearly cuts his ears off, and he has a constitution with 22 amendments.” Or how about this quick hit on a secondary figure in Ellery Queen’s The Chinese Orange Mystery (Pocket, 1962): “Hubbell: a gentleman’s gentleman—but no gentleman.”

Blatant ridicule was often a go-to move in these character briefs. In Suddenly a Corpse (Pocket, 1950), Harold Q. Masur’s second novel starring Manhattan investigating attorney Scott Jordan, we make the acquaintance of “Raymond Ainsley—Lennox Ainsley’s stepson. To know him was to hate him.” While in Queen’s The Quick and the Dead (Pocket, 1956), we meet both “Cornelia Potts—The choleric Old Woman, who ruled her roost with malice aforethought” and “Thurlow Potts—Her eldest son, a most insultable man.” Let us not overlook, either, this gem from Dell’s 1945 edition of Gold Comes in Bricks, the third installment in Erle Stanley Gardner’s series—written under the pseudonym A.A. Fair—about a pair of mismatched Los Angeles gumshoes, Bertha Cool and Donald Lam: “Robert Tindle—Carlotta Ashbury’s son who is inclined to take life a little too easy following his mother’s second marriage. His face doesn’t have any particular expression, but could be used for an ad for contented cows.”

Singular physical attributes seemed inevitably worth spotlighting. In the 1950 Dell edition of Murder with Pictures, George Harmon Coxe’s first novel starring photojournalist-cum-sleuth Kent Murdock of the Boston Courier-Herald, we learn that “Sam Cusick, a notorious gangster, is scrawny, thin-faced, with a long, drooping nose. He looks harmless—except for the expression in his ratlike eyes.” In Mike Brett’s Scream Street (Ace, 1959), we encounter “Sam Dakkers—His head was as bald as the eight-ball he found himself behind.” Dorothy Cameron Disney’s The 17th Letter (Bantam, 1947) offers up the hilariously named “Lucky Schott—Captain of the S.S. Shalimar. At first glance he looked like Santa Claus, but no one ever made that mistake a second time.” And who could forget Elvira, “a girl in her twenties,” who is imagined in Hammett Homicides, Dell’s 1948 collection of Dashiell Hammett short stories, as being “slender and lithe. Her smoke grey eyes are set too far apart for trustworthiness, though not for beauty, and she’s more dangerous than a gallon of nitrol.”

It was only unfortunate that the writers of these prefatory pages tended frequently to indulge in superfluous somatic specifics. In Curtains for the Editor (Dell, 1945), author Thomas Polsky’s inaugural outing for Midwestern newspaper reporter L.F. “Grid” Griddle, we’re tossed into the company of Carl Grouch (“managing director of the Garden of Eden night club, looks oily and calm. His hair smooth and black, his face smooth and white”), as well as Gladys Marlen (“about thirty-five, full-breasted, full-hipped, full-thighed, with a mop of hennaed hair and a pink-and-white skin that is unwrinkled, even slightly puffed”). Meanwhile, in Stuart Brock’s Just Around the Coroner (Dell, 1949), we discover “Oliver Winton, round, pink-cheeked clerk at the hotel, [who] tries to hide his youth with a sandy mustache that droops over a full-lipped mouth.”

Speaking of learning too much, note the eyebrow-raising representation, in Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s Murder Is a Kill-Joy (Dell, 1946), of “Mitzi Plummer—a very stout lady, cheerful, amiable and dark-haired, [who] is quite definitely masochistic and would love to be tortured.”

Is that meant metaphorically or literally?

* * *

So who was responsible for creating those one- or two-page ensemble inventories? Charles Ardai, the editor at New York City-based Hard Case Crime—which publishes pulp-style fiction, both new and classic—speculates that it was “the same person who wrote back-cover copy and came up with the excerpt for the teaser page, which I’m assuming must have been the editor.” It certainly had to have been someone intimately familiar with the story at hand, especially when player renderings were more than merely extracts from the main text. The novelists themselves probably had little or no hand in crafting these content elements, though they benefited from having witty cast depictions kick off their work.

You might be surprised to learn that it’s not generally the leading men or women in these books who are most engagingly appraised in “Cast of Characters” entries. Sure, there are exceptions. In Mark Kilby and the Secret Syndicate (Pocket, 1960), John Creasey—writing under the alias Robert Caine Frazer—defines series hero Kilby as “an alertly poised, debonair Englishman, employed as an investigator by a multimillion-dollar international investment corporation, [who] was as deft with a beautiful woman as he was with his deadly switch-blade cane.” Frank Gruber’s The Buffalo Box (Bantam, 1946) tries to stimulate reader curiosity with this cryptic come-on: “Simon Lash—a crack private detective, had it; lost it; but regained it.” And in The Bigger They Come (Pocket, 1953), the first of Gardner’s 30 spirited Cool and Lam tales, greedy and corrupt investigative-agency proprietor Cool is colorfully pictured as “a sizable chunk of woman with the majesty of a snow-capped mountain and the assurance of a steam roller.” Of Lam, the disbarred lawyer and certified romantic whom she employs to do most of the snooping, it’s said simply that he’s “a physical weakling, but a mental giant.”

More often, subordinate actors score the prize profiles:

Jules Langley—A paunchy jeweler with a mouth like a locked purse, he performed services for rich and poor impartially—he cheated them both. (Miami Mayhem by “Anthony Rome,” aka Marvin H. Albert, Pocket, 1960)

Article continues after advertisementChief Dakin, Wrightsville’s Chief of Police, who combined the look of a terrapin with the mouth of a poet. (Calamity Town by Ellery Queen, Pocket, 1955)

Lieutenant Matt Conroy—Of the Homicide Squad; a splendid detective with the finesse of an elephant. (Widow’s Pique by Blair Treynor, Permabooks, 1957)

Alonzo Platin—He was a rich man who collected jade, gold, and human souls. (My Enemy, My Wife by Allen Haden, Dell, 1952)

Anthony Goodwin—a refugee English poet whose genius is to madness near allied, he says. He has long, intense limbs and a long, intense aversion to toil. (Fire Will Freeze by Margaret Millar, Dell, 1947)

Morgan Birks—an unfaithful husband being sued for what unfaithful husbands are usually being sued for. (The Bigger They Come by A.A. Fair, Pocket 1953)

Article continues after advertisementSikorski—a concert pianist with a past mixed up with Mrs. Robjohn’s. Thinks he might have children somewhere because “these things happen.” (She Shall Have Murder by Delano Ames, Dell, 1951)

Miles—the close-mouthed Harper chauffeur, looks like Humphrey Bogart, except that Bogart never looked so tough. He is cold as an eel and as expressionless as a bottle of beer. (The Rat Began to Gnaw the Rope by C. W. Grafton, Dell, 1947)

I can’t fail to recognize, either, this predictive sketch:

Pete—a good guy but his time was up. (Murder Is Dangerous by Saul Levinson, Handi-Books, 1951)

Women were accorded no less attention than men on these character pages, though—the mid-1900s having been an even more blatantly sexist era than our present day—it was not always for flattering reasons:

Christine Vanlinden—Beauties are a dime a dozen in a Charteris thriller, but it will be a long time before there will be an equal to this copperhead bundle of T.N.T. (The Saint at the Thieves’ Picnic by Leslie Charteris, Avon, 1952)

Mildred Havens—Aunt Mildred works her fingers to the bone making everybody comfortable, but she also works her tongue twice as hard making conversational excursions into everyone’s privacy. (Crimson Friday by Dorothy Cameron Disney, Dell, 1946)

Enid Monck—A loquacious ex-actress whose star had gone out with silent films, she rebelled against middle age by donning war paint and attempting to seduce every eligible male aboard—and some who weren’t eligible. (Many Brave Hearts by Donald M. Douglas, Pocket, 1960)

Mary Helen Crane—Nella’s niece has large eyes, a long chin, and a babyish mouth. She is not pretty but one keeps wondering why not. Her entrance into the Peabody house changes its tempo from cool placidity to something almost feverish. (The Glass Mask by Lenore Glen Offord, Dell, 1947)

Louisa—Ed’s stepdaughter and very beautiful, is supposed to have just recently come home from a convent, but Louisa has knowledge she hasn’t learned in a convent. (The Baited Blonde by Robinson MacLean, Dell, 1951)

Chicago bookseller and blogger J.F. Norris, who ferreted out a number of the descriptions featured in this piece, draws special notice to the following three portraits of women appearing in Henry Kane’s Until You Are Dead (Dell, 1952), a Pete Chalmers gumshoe novel that he says concerns “a murder in a strip club, and the world of two-bit entertainers, musicians, and vaudevillians facing their swan songs”:

Rhonda Carson—Kermit’s girlfriend, is a half and half blonde: half promise and half ice water.

Bobo O’Sullivan—a long-stemmed beauty in gold shorts, owns some very interesting real estate, both animate and inanimate.

Sari Malloy—a masterpiece of feminine architecture and billed as Johnny’s sweetheart, provides a private eyeball with a really sumptuous private eyeful.

Such snappy wordplay was the stock-in-trade of folks who composed “Cast of Characters” pages (or, as Dell headlined its lists, “Persons This Mystery Is About”). As an example, in Gardner’s third Perry Mason novel, The Case of the Sulky Girl (Pocket, 1962), we find “Rob Gleason, who discovered that where there’s a will there’s sometimes a won’t,” along with “Harry Nevers, Star reporter, who (when it came to cheesecake) was only a legman at heart.” Queen’s The Dragon’s Teeth (Pocket, 1947) presents “Margo Cole, a French importation, garbed attractively in a tight dress and loose morals.” The same author’s previously referenced Chinese Orange Mystery gives us “Jo Temple: whose knowledge of Chinese helped Ellery get oriented.” Let Him Go Hang (Ace, 1961), a legal thriller by “Bud Clifton,” aka David Stacton, delivers “Jan Sibley—She voted to convict the accused, but her vote was not of her own conviction.” And in one of Gardner’s mid-series Cool and Lam puzzlers, the amusingly titled Shills Can’t Cash Chips (Pocket, 1970), we run across divorcee and recent car-accident victim “Vivian Deshler—This blonde, with lots of this and that and these and those, was accused of wrongs but knew her rights.”

- Ace D-501 Paperback Original (1961)

* * *

Sadly, when Hard Case Crime issued its paperback reprint edition of Shills Can’t Cash Chips in November, there were no “Cast of Characters” pages in evidence. Ardai explains: “That was a bit of an affectation that dates back to the 1930s/’40s, I believe, and feels older than our sweet spot—by the 1950s (the heyday of the paperback original), I think they were mostly gone. I generally like archaic touches like that, but that one somehow felt a little too old-timey even for us.”

He goes on to say that, although character-briefing pages “were cleverly worded (sometimes), they also sometimes feel too spoiler-y, since they tell you about who you’re going to meet in the book and on what page you’re going to meet them—it can be too much information.”

Ardai does have a point. Although it wasn’t always the case, some player listings read rather like plot synopses. Check out this opening succession of briefs from Helen McCloy’s Through a Glass Darkly (Dell, 1951):

Faustina Crayle, an art teacher, is deeply distressed at being discharged from her job without explanation. A shy, gentle, and quiet girl, she is at a loss to account either for her abrupt discharge or for the peculiar attitude of her associates who avoid and seem to fear her.

Gisela von Hoenems, Faustina’s friend, is a young German teacher who came to America as a refugee. Gisela is even more in a quandary than Faustina as to the cause of the terror Faustina seems to instill in others—but she senses something sinister.

Dr. Basil Willing, distinguished psychiatrist and medical consultant of the New York district attorney, is in love with Gisela. Because of her fears for Faustina, Dr. Willing becomes interested in the sinister happenings that have occurred and seeks a solution.

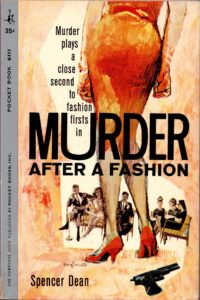

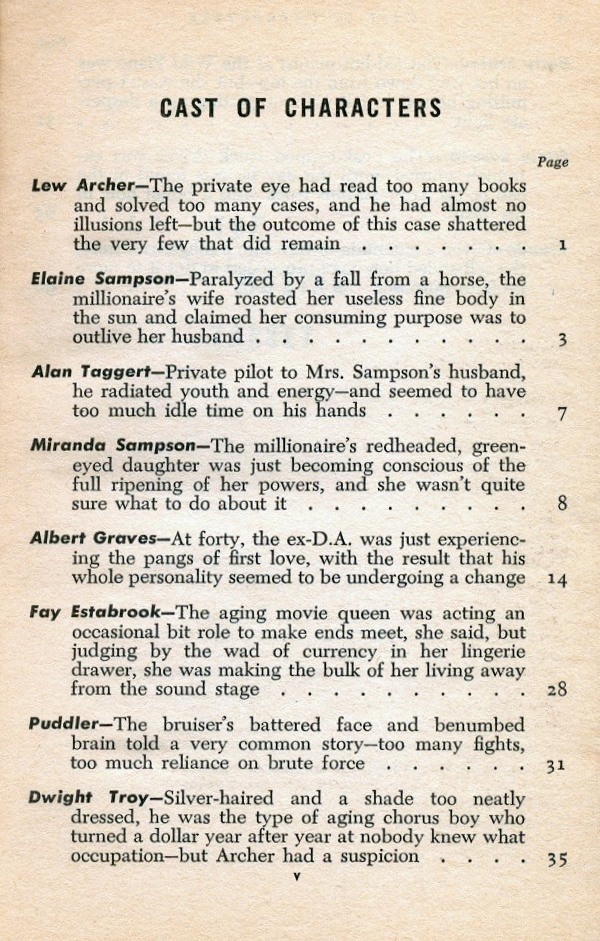

This next partial lineup comes from Murder After a Fashion (Pocket, 1961), a lively whodunit set in a Manhattan department store and penned by Prentice Winchell under his nom de plume Spencer Dean:

Enid Amesbury—Ambletts Fifth Avenue’s shrewdest buyer, her fashion secrets were sheer nothing next to the mysteriously designed murder weapon found in her salon.

Bruce Huffbitter—A beat, bona fide bastard, his knife-wielding, acid-throwing, razor-slashing scene made the police wonder if he had murder up his sleeve.

Don Cadee—The store’s fast-moving Protection Chief, he followed a loose thread from New York to Nevada and back, and wound it up in the five-and-ten-cent store.

Sibyl Forde—Don’s clever and devoted double-life helpmate, her dinner á deux was postponed until they could solve a double murder.

In both samples, the writer has sought to build intrigue and quickly make the reader care about what’s to befall the people involved. However, we are ultimately left unsatisfied, teased with facts that shed but faint light upon the performers and simultaneously leach surprise from plot turns yet to come. Sometimes a simpler approach to clueing readers into what they can expect from a novel works far better. Below is the entire text of a page titled “The Characters,” taken from the 1948 Dodd, Mead hardcover edition of Christianna Brand’s Death of Jezebel and sent to me by British novelist Martin Edwards:

Johnny Wyse, who died; and to avenge whose death two of the following also died—and one was a murderer

Isabel Drew, a Jezebel

Edgar Port, just a sugar daddy

Earl Anderson, “a poor player”

Brian Bryan, a knight in armour

Perpetua Kirk, a damsel in distress

George Exmouth, a very young young man

Susan Betchley, a not very young young lady

If only it were true that all “Cast of Characters” pages aspired to the same level of waggery, charm, and titillation as the depictions quoted above suggest. Alas, many were perfunctory efforts at best, lacking in inventiveness or intrigue. They existed solely out of adherence to a publishing line’s format. Knowing that, though, should cause readers to appreciate truly creative specimens of this breed all the more.

So the next time you crack open (with care) one of those much-thumbed paperback crime novels from the mid-20th century, look to see whether there’s a register of dramatis personae upfront. If there is, take a few moments—just a wee tick out of your life—to peruse the entries before moving on. I confess, it will please my heart to know that those now largely forgotten pages are being noticed again by other people than me.