I love the show Moonlighting, but everyone loves Moonlighting. To see Moonlighting is, in fact, to love it, though if you didn’t watch it when it aired, from 1985 to 1989 on ABC, there’s a chance you may never have seen it. None of its five seasons are available in digital versions, for purchase or subscription streaming. The handful of DVD editions produced in the early 2000s are out of print. The only way to watch it now is via a mélange of YouTube postings, or to get your hands on those rare physical copies (which is what I did, via many stressful eBay auctions, tortured soul that I am). The eventual obscurity of this show is, as far as I’m concerned, a crisis. Moonlighting, an hour-long mystery series which ran on Tuesday nights, is about the unlikely pairing of a tough, Type-A former model (played by Cybill Shepherd) and a scrappy, motormouth PI (a then-unknown Bruce Willis), who team up to run a detective agency. It is endlessly entertaining. It is full of energy and pathos, of lust and tension, of joy and laughter—a firecracker of a program whose antics feel not only amusing, but also, in a way, moving. Watching it, you can’t help but find it special.

I confess that I didn’t watch Moonlighting when it aired, not having been born until a few years after it ended. But Moonlighting is a timeless, nostalgic show—initially owing much of its personality to Golden Age Hollywood’s screwball comedies and noirs, plus assorted odds and ends from other film and television genres. As the seasons went on, Moonlighting began to experiment with form and aesthetics. There were referential acknowledgements of the camera, extended dance sequences, and one Zeffirelli-esque Shakespearean episode spoken (almost) entirely in iambic pentameter. Moonlighting gave Bruce Willis his start. It gave Cybill Shepherd her comeback. There were glittering evening gowns, big-budget and high-flying climaxes, and zinging banter slung so deftly that you might have forgotten you weren’t watching Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant. There was chemistry so palpable and powerful it’s a wonder why every TV set in America didn’t burst into flames every week.

The story of Moonlighting itself—that is, making Moonlighting—is no less fiery. There were real-life feuds, backstage fireworks, and an always-behind production schedule that promised more episodes than were ever delivered. According to crew members, sometimes scenes would be filmed for an episode that needed to air that night. One crew member remembers handing in a full episode to the studio a half hour before its air time. In the show’s final seasons, its two lead actors became less involved; Cybill Shepherd because she was pregnant, and Bruce Willis because he had made it big. After becoming the (singing) spokesperson for Seagrams Wine Coolers, Willis became an action star in 1988’s surprise hit Die Hard, and thus became extremely unavailable for Moonlighting commitments. To sustain itself, the show began to spotlight its lovable minor characters, two agency employees named Agnes DiPesto (Allyce Beasley) and Herbert Viola (Curtis Armstrong), who, while adorable and charming, didn’t supply the romantic voltage that drew viewers to the show in the first place. But by the time it was cancelled in 1989, after the behind-the-scenes problems had completely engulfed the actual process of making it, it had still accomplished something vanguard, and brought something new and wonderful to television.

* * *

It’s impossible to say all the ways in which Moonlighting influenced television that came after it. Its wacky breaking-the-fourth wall, mile-a-minute jokes, throwaway references that not all audience members might even understand place it in a lineage of television’s smartest, most sophisticated situation comedies. And its particular, zany take on the “lighthearted detective show” gambit was new, too—whenever I watch a show like Psych, I am overcome by the debt owed to Moonlighting. But Moonlighting’s impact was also extremely personal. One of these days I’ll launch an essay contest, a “what Moonlighting means to me” sort of deal. It made an enormous impact. The television critic Howard Rosenberg, who had panned the show upon its release, wrote a correction a few weeks later to apologize for not having understood Moonlighting and to confirm that he had since seen the light. After its startling first season, it had become such an enormous sensation that (according to people who were alive in the 80s) Moonlighting became the ubiquitous conversation topic on Wednesday mornings at work. Two years after it aired, sixty million viewers tuned in to watch the protagonists finally hook up, in a passionate (edgy for prime-time) sex-scene that involved destroying every nearby prop. (Anyone who wants to read about this, more in-depth, should pre-order Scott Ryan’s official book on the series, which is due out in June 2021.)

It’s funny, because the circumstances in which I first saw Moonlighting (on YouTube, in 2014, after my mom had recommended it) were almost relatively meaningless to me. I watched it almost in a vacuum—devoid of any advertisements, hype, the strange (plot-spoiling) TV trailers that were ubiquitous on ABC before its premiere on March 3rd. And yet I was entranced. Not that I ever mind watching something that is a relic of its own era of production, but I didn’t need any context to connect with what I was watching. Moonlighting didn’t feel like a product of the 80s so much as an accumulation of the entire entertainment world that came before it—a world that I already loved.

Moonlighting is about two people, two complete opposites, with absolutely no romantic history, who nonetheless build a rich romantic history for themselves—one scrapped together from a long archive of mainstream pop culture.Moonlighting is about two people, two complete opposites, with absolutely no romantic history, who nonetheless build a rich romantic history for themselves—one scrapped together from a long archive of mainstream pop culture. Our protagonists, Maddie Hayes and David Addison, are “moonlighting” in that neither one of them has any (figurative) business in literally operating a detective business, but they are also “moonlighting” in a more abstract sense, slipping in and out of various love stories… borrowing the best elements from a great syllabus of romances, from William Shakespeare to Howard Hawks to Raymond Chandler, giving themselves the opportunity to enjoy falling in love over and over, in all these many styles and moods.

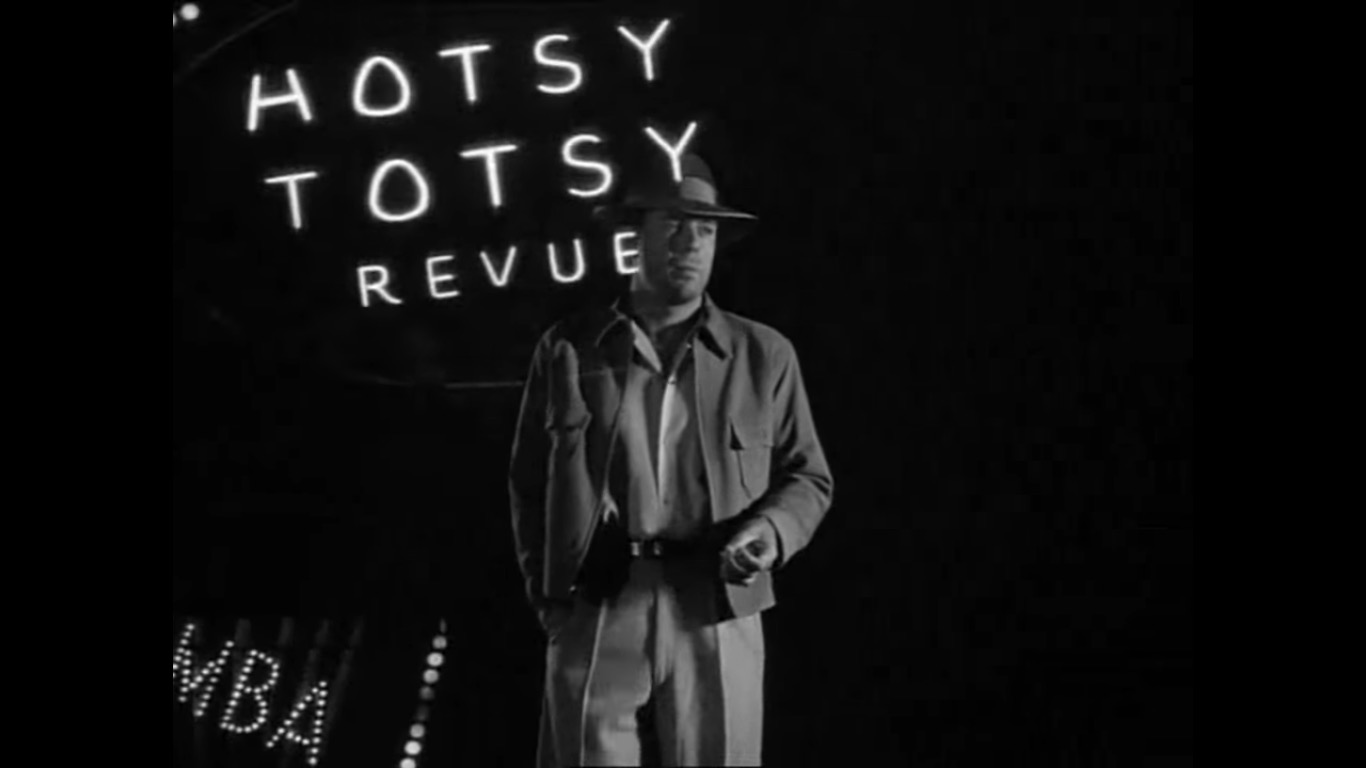

So often, Moonlighting is a string of fantasies. The show dreamily wonders what its characters would look like—how they would spar, how the sparks would fly—in other aesthetics, and so blinks them there. No greater example of this occurred than when writers Debra Frank and Carl Sautter wrote them an episode shot entirely on real black-and-white film stock entitled “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice.” The show’s creator Glenn Gordon Caron had been informed by the studio to record it in color and have the picture altered later, but he insisted it needed to be recorded on the genuine material from the era they were capturing. The episode, which you can watch in full on YouTube, is marvelously grainy, with dipping, swooping shadows, by cinematographer Gerald Perry Finnerman. Looking at it, it’s nearly impossible to tell that it was made forty-five years after Humphrey Bogart played Sam Spade.

And, emphasizing its investment in film history is its best cameo: the episode is presented to the audience with an introduction from an elderly Orson Welles, who informs the audience (in color) that their screens are going to play the episode in black-and-white, and assures them that the “monochromic, monophonic” transformation they will witness twelve minutes into the broadcast is not a malfunction on the part of their sets. The writing team noted that when Welles recorded his scene, the stage had filled with crew members, quietly, respectfully watching the master at work. Welles would die exactly one week later. It was the last thing he made that would air during his lifetime. It was his last performance.

“The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” isn’t really a mystery (it’s two dream sequences, one for Maddie and one for David, that imagine outcomes of a cold case from 1946). That’s fine, because Moonlighting isn’t really a detective show, anyway. Yes, there are cases, but just enough. The detective agency is the pretense, and frequently, this shows. Its creator, the twenty-six-year-old Caron, had been given an opportunity to develop some pilots for ABC, and Moonlighting was his third. He had been specifically instructed to write a “boy-girl detective show,” a rote genre which Caron despised. He had written some episodes of Remington Steele (a more traditional mystery show that ran from 1982-1987 and starred a young Pierce Brosnan as a thief who pretends to be a detective to work with a cool lady PI, I KNOW), but didn’t have much experience with the genre. Moreover, he had little interest in writing something that felt so formulaic. But the more he protested, the more leeway the studio gave him. He would later say (in the interview on one of my Moonlighting DVDs) that Moonlighting appeared to break so many rules (of the detective show format, of television in general) because he had never actually known “what the rules were.”

Make no mistake, Moonlighting is about the central relationship between Maddie and David, and the precise nature of this relationship is ultimately the central mystery. When will they realize they are soulmates? Do they already know? From the moment the two meet, their personalities chafe and clash. The theme song, with lyrics written and vocals provided by Al Jarreau, refers to them as “moon” and “sun”—two strong, elemental antipodes cosmically, perhaps even magnetically drawn to one another (I don’t remember eighth grade earth science, bear with me). Maddie is a no-nonsense former model (famous for being the “Blue Moon Shampoo girl”) whose business managers have just (legally) robbed her of her life savings. But she discovers that she owns several businesses (including a detective agency) as tax write-offs. She shuts them down, but when she arrives at the last one, the City of Angels Detective Agency, she can’t manage to do it. That’s because its proprietor, the loud, constantly-quipping wiseass gumshoe David Addison begs her to go into business with him, to turn the company around. A series of misadventures, which leads them to a treasure hunt for hidden Nazi diamonds, ultimately convinces the reluctant Maddie of their compatibility, or at least viability. It’s clear (to everyone) that they, fire and ice, will fall passionately in love. The fun is watching the ardor stall for as long as possible.

Moonlighting is about the central relationship between Maddie and David, and the precise nature of this relationship is ultimately the central mystery.Cybill Shepherd notes, in an interview, that this tension was maintained because she and Bruce Willis were “never lovers” in real life, though by all accounts, mutual attraction was there. Caron had to promise the studio that the relationship would not become romantic right off the bat, in the two-hour pilot, mostly because the executives (who were skeptical about the ever-so-slightly-crass Willis) could not believe that he would ever conceivably be the object of affection for someone as polished as Shepherd. But Caron thought the tension between a sloppier huckster of a man and an elegant woman was essential for the gambit—if he had been making a film version, Caron said, he would have cast Bill Murray and Jessica Lange.

Caron was sure that Shepherd and Willis would have sparkling chemistry, despite not actually having seen them act together (Shepherd, who had signed onto the part after seeing a mere half a script, was terrified that she might be replaced if she did a screen test, so she refused—though she needn’t have worried, because Caron wrote the part with her in mind). Caron’s intuition was on the money: they were a perfect match. (Willis jokes that the real screen test was in the elevator ride on the first day of shooting, where he met Shepherd in person and he wouldn’t stop flirting with her.) Eventually, their mutual interest turned to competitiveness and ire; they wound up fighting before every single (scripted) fight scene. But their friction only seemed to fuel their onscreen dynamic. Back before production had even begun, when Shepherd had read Caron’s script, she excitedly told him that he had inadvertently written “a Hawksian comedy,” and obligatorily within that, a kind of glamorous, witty female leading role bursting with vim and fizzing with repartee. An ardent fan of screwball comedies, she had always dreamed of a part like this.

Maddie Hayes is fierce; she suffers no fools, and this is rotten luck for David most of the time. Maddie’s contribution to the comedy comes from her transformation—her acceptance of and eventual participation in the cockamamie circumstances in which she finds herself and which are often David’s fault—as much as her conviction. She bosses David around because she is serious, but she isn’t so serious that she winds up doing all the (emotional, or literal) labor. David, who appears at times to be an immature clod, is hopelessly clever and relentlessly brave. He’ll jump in the path of a shooter, or leap on top of a moving train. Maddie is brave, too—though she’s more calculating than her partner. In the pilot episode, she scales a level of Los Angeles’s Empire clock tower in a pencil skirt and heels, as calmly as if she’s ascending a staircase at a gala, wearing one of her fabulous gowns.

It’s noteworthy, also, how both of these actors become so funny in their comic parts—Shepherd for her glowering glances and cranky intonations, Bruce Willis for his sound effects and willingness to loudly burst into song (or trill into a harmonica) at a moment’s notice. (Because of all his riveting shenanigans in Moonlighting, I find that Willis’s subsequent, totalizing career as an action star is a bit of a shame, because it has suppressed the roles he might have taken that allow him to be a total ham, and he’s so, so good at that). But, as I’ve said, the funniest part of the show is the rapier-raillery, a volley of puns and cracks so crackling that you’ll rewind your Moonlighting DVD three times to catch everything (or record it with your iPhone and text it to all your group chats, ahem).

Moonlighting’s charms superseded the familiar “battle of the sexes” framework it naturally employed. Though Maddie and David were obviously in love the whole time, the forestalling of their relationship led to them establishing a dependable, beautiful friendship. They were partners, neither with the professional upper-hand nor greater industrial know-how. They were resourceful, kooky, ride-or-die friends. Best friends.

Crew members—writers and other artists—noted that the atmosphere on the show was especially friendly and loving. In part because of Caron’s freewheeling showrunning, which allowed writers to have fun with their scripts and even make obscure jests that audience members might not understand, it became Moonlighting’s ethos that the team wasn’t writing a show to please anyone, least of all network executives—they were doing it to make the kind of show they, themselves, wanted to watch. Caron wound up going to bat for his strange (and often big-budget) production countless times, promising skeptical executives that whatever unconventional turn the show would take, would wind up enormously successful.

Key to the soul of Moonlighting is the knowledge that it is a pastiche,that it is meta. But its reflexivity isn’t merely a gag, it reflects a particular investment. In a show that is so much about teamwork, friendship, love (and also, conversely, “winging it” while shooting for the stars), it became increasingly meaningful to illuminate the relationship between the performers and the crew—that everyone on set was “in” on a joke together, that behind the effortless, dueling bon mots were teams of laughing writers. No episode emphasizes this more than Season Two’s Christmas episode, in which the camera pulls away from David and Maddie to reveal an entire soundstage packed with staffers.

Crew members had received last-minute notice to come to the studio that day, and bring their spouses and children, to make an ensemble appearance. As the camera pulls out away from the two stars, revealing the village it took to make Moonlighting possible, everyone starts to sing, together. The song is the carol “Noel.” Actress Allyce Beasley, who plays the agency’s rhyming secretary Agnes, says of this moment that “there was a feeling in the air you could almost touch,” for its being “so tender and so sweet.” The show’s theme song promises a unification of “moonlighting strangers who met on the way,” and here was a room full of them, once unknown to one another, and now a passionate group of friends. Besides that this scene was formally innovative, it was also sentimental. It was loving. Indeed, as other crew members noted, “every day” making Moonlighting “was special.”

I wish so badly that Moonlighting were accessible via some sort of streaming platform (really, ABC, we are in a *pandemic*… now is the time to do it… it will make so many people furiously gleeful, I promise). While episodes are up on YouTube, this only makes them available for people who specifically search for them. I don’t often write essays so bereft of thesis statements—rather, essays in which my thesis statement is really just an adulation or a recommendation. But it seems silly to try to dig far into Moonlighting analytically when no one else can feasibly watch it. Instead, this essay serves to ask you to remember it, to try to revisit it, or to do what you can to meet it for the first time. Moonlighting is a show about loving movies. It is a show about loving form, and genre, and history. It is a show, such a niche show, that was made to simply be fun, to make fun with friends and the people you came to love. And for all these reasons, it is nothing short of magic.