Introduction: Game of Bones

The sudden death in Hollywood, where he was working on the script for what was then termed RKO’s “gorilla picture” (aka King Kong), of English crime writer Edgar Wallace at the age of fifty-six on February 10, 1932 was an epochal event within the world of British crime fiction, comparable in its own admittedly more restricted way to the demise of Queen Victoria three decades earlier. At least in the case of the late Queen the line of succession to the throne was clear and secure. In the case of “shocker king” Edgar Wallace, however, Death sent numerous pretenders scrambling to grab the master’s highly lucrative diadem, with all of the publishing glories it entailed. Call it vintage crime fiction’s Game of Bones.

What followed in the UK was not the War of the Roses but rather the War of the Rozzers, if you will, as hopeful authors attempted to show that they had what it took to become the new King of Shockers, producing book after book about tough, square-jawed Scotland Yard police detectives and their criminal mastermind opponents, those sinister men with queer handles and even queerer underlings: wild-eyed Bolsheviks, slinky adventuresses, conniving Levantines, wicked “Chinamen,” dastardly “dagoes,” rascally Ruritanians and the like. And let us not forget those stalwart (if not notably brainy) young heroes and their imperiled, virginal lady loves, whose virtue was as unquestioned as their remarkable knack for getting kidnapped, bound and gagged and flung to their watery dooms into rapidly flooding locked cellars.

One of the most important pretenders to Edgar Wallace’s crime throne was Nigel Morland (1905-1986), who though only twenty-six years old when Edgar Wallace shuffled off his mortal coil had been, or so he claimed, the Great Man’s secretary at one time. Three years after Wallace’s demise Nigel published with Cassell The Moon Murders (1935), the first of his thrillers headlined by a boisterous, ruthless, ambiguously female sleuth, Mrs. Palmyra Evangeline Pym, which he dedicated to the late Crime King. Nigel claimed that Wallace had given him the idea for Mrs. Pym back in the 1920s (see below), though in fact, given her brutish demeanor and authoritarian behavior, she could have been inspired by the severely mannish pioneering English volunteer policewoman Mary Sophia Allen, who during the Thirties met with Hitler and joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. “I would like to see Mrs. Pym box ten rounds with Commander Mary Allen,” critic Maurice Richardson drolly avowed in 1940, in his London Observer review of The Clue of the Careless Hangman (1940).

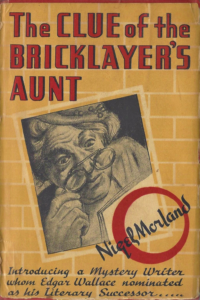

Boosted by its lead character, who in crime fiction was nothing if not novel, The Moon Murders was a success in England. Nigel Morland quickly published two more Mrs. Pym mysteries, The Phantom Gunman (1935) and The Street of the Leopard (1936), which did similarly well in his native country. Nigel’s fourth Mrs. Pym adventure, The Clue of the Bricklayer’s Aunt (1936), was picked up by American publisher Farrar & Rinehart, who would issue seven additional Mrs. Pym novels in the United States. Altogether the Mrs. Pym series would run for over a quarter-century from 1935 until 1961, well past the end of the Golden Age of detective fiction. The series numbered twenty-two novels and some short stories as well, though fully a dozen of the novels appeared between 1935 and 1943, a period which might be termed the palmy days of Mrs. Pym.

As Nigel Morland’s most famous series character, Mrs. Pym was nothing if not outsize: a snorting, snarling, scowling, brawling—one is tempted to say ball busting—lady detective, specifically nothing less than Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. She has been disparagingly dubbed “Mike Hammer in a dress” and likened to thriller writer Sapper’s public-school hero Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond, an odious individual, in my estimation, who throughout his hugely popular adventures carried with him, as Richard Usborne noted in his book Clubland Heroes, “a whiff of bullying…and fascism.” In a 1958 number of his “Crime Corner” column in the Cardiff Western Mail, reviewer Harry Green bluntly stated: “I can’t stomach Nigel Morland’s Mrs. Pym. There are neo-fascist elements in us all, but we do our best to keep our personal Bulldog Drummond in its kennel; Mrs. Pym is a female Bulldog and one of the nastiest conceptions in modern detective fiction.”

Certainly, throughout her adventures Mrs. Pym was no feminist, if that is understood as a friend to other women. In The Clue of the Careless Hangman the ungentle lady threatens to disable an uncooperative female prisoner’s reproductive system by viciously kneeing her in the groin if she does not give her the information she wants, while in The Case without a Clue (1938), she mocks her loyal if dim myrmidon, Detective Chief-Inspector Shott, when he is smitten with an attractive woman in the case. “I don’t trust any woman,” she snarls, reminding Shott: “I’m one myself and I know what a bunch of immoral hussies we—they are.”

This sounds like a weird and fantastic, if not utterly unbelievable and rather repulsive, character, and, indeed, I think it is fair to say that Mrs. Pym is precisely such. In 1979 Nigel Morland declared that his chromosomally female sleuth “pioneered two well-established modern manias—the sex change and women’s lib.” However, I agree with mystery authority Douglas Greene’s riposte five years later that “Mrs. Pym’s aping of men” was not a signpost to the future of crime fiction but rather a detour away from it, since the “current direction is toward capable women who have not given up all womanliness.”

Nonetheless, Mrs. Pym claimed some popularity in her day, particularly in her country of origin—though even in the UK not a few critics, like Harry Green, divided decisively from her devotees. A common complaint lodged against Morland’s Mrs. Pym mysteries by their denigrators was that the stories began promisingly, only to disintegrate into a muddle of mere sensation and daft illogic. The poet W. H. Auden, both a devotee and theorist of tales of classic detection, having read The Clue of the Bricklayer’s Aunt, disgustedly pronounced Mrs. Pym “probably the most unpleasant detective in modern fiction,” adding cuttingly that “[t]hose who prefer car chases, street fights and violent action to credibility, logical reasoning and style, and who believe in treating the criminal rough” would like her.

For his part the esteemed mystery critic and crossword expert “Torquemada” (Edward Powys Mathers) initially dismissed Mrs. Pym as an “entirely ludicrous and impossible character” and wittily observed of the formidable if fantastical lady: “When she is about, there is humour; but if it is not quite unconscious, it is badly dazed.” However, Torquemada succumbed to the distaff cop’s charms by the third and fourth books in the series. Intriguingly after Torquemada’s death in 1939 Nigel Morland claimed that the critic personally stepped in and tutored the younger man in improving his crime writing. Admittedly Nigel’s truthfulness about his acquaintanceship with prominent personages over the years is often in doubt (see below), but certainly Torquemada’s opinion of the Mrs. Pym series rose before his untimely demise.

In Australia, prominent journalist Richard Hughes, who reviewed crime fiction under the name “Dr. Watson, Jun.,” chidingly placed Nigel Morland on his “index of banned detective writers” for having “sinned irredeemably against the solemn canons of honest detection” with his Mrs. Pym mystery The Corpse on the Flying Trapeze (1941), in which a visiting Mrs. Pym foils a heinous plot to assassinate the American president. The sexist Hughes found the novel so flagrantly and “callously” unfair as a puzzle that he suspected its author was really a woman using a male pseudonym (which also explained, in his eyes, the presence of Mrs. Pym). Noting that Morland had composed “a treatise called How to Write Detective Novels,” he sarcastically added: “I recommend it to the serious student of conchology.” Later in the decade he dubbed Mrs. Pym fiction’s “most loathsome creature in Scotland Yard” and, outdoing himself in invective, “that arrogant, hebetudinous, saurian horror-woman.”

Although notoriously the United States was the native ground of celebrity gangsters, hit jobs and the third degree, Mrs. Pym was not as well-received there as she had been in the mother country. Evidently Americans knew ersatz crime fiction when they saw it. The erudite Anthony Boucher dismissed Nigel Morland as a “third-rate Edgar Wallace,” while another reviewer, aggrieved at having to read a second Mrs. Pym mystery after having suffered through one already, complained: “We have never been given any rational explanation of how Mrs. Pym came to occupy the position she does in Scotland Yard, but there she is and there she will stay so long as Mr. Morland continues to write stories about her….One might gather from this that we do not like Mrs. Pym, and the conclusion would be quite correct.” Yet other American critics chimed in with pithy Pym disses like these:

Nigel Morland is said to have been trained by the late Edgar Wallace as his successor. It seems to me that Mr. Wallace did not live long enough to complete the job.

This whodunit gives you a run for your money, but it turns out to be pretty small change in the end.

Nigel Morland’s American publisher, Farrar & Rinehart, dropped Mrs. Pym with the onset of America’s entry into World War Two and the author never gained any real foothold in the country again. However, in the UK, where in the Fifties an admiring “Mrs. Pym Club” was formed, the battered old bird maintained a loyal following of lending library enthusiasts as Mrs. Pym returned to solve ten more cases in novel form, beginning in 1947 with Dressed to Kill and ending in 1961 with The Dear Dead Girls. There was even a brief revival in 1976 when a nostalgic collection of Mrs. Pym short stories was published in Britain, complete with an introduction by Eric Ambler, of all people.

Like his rival Wallace School contemporaries Sydney Horler and Leonard Gribble, Nigel Morland was an extremely prolific author, publishing crime fiction and other works under a myriad of pseudonyms. There was Norman Forrest (two books), John Donavan (six books), Roger Garnett (nine books) and Neal Shepherd (four books), not to mention a couple of singletons, Vincent McCall and Mary Dane. Then there were the crime books signed “Nigel Morland” that did not have Mrs. Pym in them—at least thirteen of those. We are up to fifty-eight books and I have not exhausted his output yet. There were also tomes on true crime as well as criminology and scientific detection, but Nigel’s well of fiction dried up in the Sixties, with the author finally confessing, according to 100 Great Detectives (1991), that detective stories “bored him to tears.”

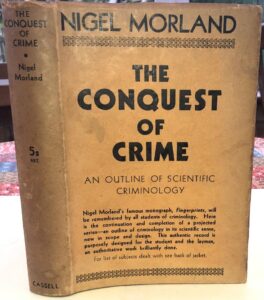

Nige Morland’s evident first love as a writer was true crime. As far back as 1936, when he published his 500,000-word opus The Conquest of Crime: An Outline of Scientific Criminology, Nigel claimed that detective fiction for him was merely “recreation from scientific study of criminology.” Among his youthful pearls of criminological wisdom were that blonde women made “the most depraved, merciless and cruel of all criminals,” a conclusion that doubtlessly would have gratified Hollywood, and that nearly half of crimes could be “attributed, directly or indirectly, to prostitutes.” He boasted that when finally completed his Encyclopedia would be 2,500,000 words long. Eighteen impressed American police departments had invited him to speak to them in the US, he declared. He claimed he also used to do a lot of “checking-up” on factual details for Edgar Wallace.

Nige Morland’s evident first love as a writer was true crime. As far back as 1936, when he published his 500,000-word opus The Conquest of Crime: An Outline of Scientific Criminology, Nigel claimed that detective fiction for him was merely “recreation from scientific study of criminology.” Among his youthful pearls of criminological wisdom were that blonde women made “the most depraved, merciless and cruel of all criminals,” a conclusion that doubtlessly would have gratified Hollywood, and that nearly half of crimes could be “attributed, directly or indirectly, to prostitutes.” He boasted that when finally completed his Encyclopedia would be 2,500,000 words long. Eighteen impressed American police departments had invited him to speak to them in the US, he declared. He claimed he also used to do a lot of “checking-up” on factual details for Edgar Wallace.

The criminologist’s professed later-in-life weariness with detective fiction notwithstanding, Nigel for three years in the mid-Sixties edited the Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine, which was certainly full of the stuff. Additionally, in 1966 Edgar Wallace’s youngest child, Penelope Wallace, tapped him to edit a new press which she had started (or been urged by Nigel to start), named Tallis in honor of the publisher of Wallace’s famed debut 1905 thriller, The Four Just Men. It was said that Tallis would specialize in crime fiction and “fast-moving adventure,” but in the event it seems primarily to have devoted itself to publishing reprints of old Edgar Wallace shockers, along with ripe specimens of illustrated, “adults-only” titillation, such as Vice in Bombay (Prostitutes…child sex shows…blue films…boy brothels…a sin-soaked sexual abyss revealed in all its shocking excess!); Blackbirds: A Photographic Collection of Beautiful Coloured Girls; The Americas after Dark: An Illustrated Guide to the Strippers, Call Girls and Drunks of the Cities of America; Flagellation: The History of Corporal Punishment; and Ladies of Vice: The Story of Prostitution, Unabridged, Unexpurgated, Uncensored.

In these later years of his life Nigel also edited The Criminologist, which during the Seventies he made a haven for Jack the Ripper conspiracy theorists (see below). Back in 1936, Nigel, identifying himself as a “British criminologist,” had confidently divulged to Roger D. Greene, an American journalist with the London office of the Associated Press, that the “Ripper was an eminent London physician, adding: “[B]ecause he was an intimate friend of royalty, the case was hushed up and he was put in an asylum.” How Nigel came to know this was left unexplained, but he later filled in the blanks, however falsely.

Nigel Morland frequently asserted that he was writing a biography of his mentor Edgar Wallace, although this bio never actually appeared. In 1986 the venerable crime writer and self-professed criminological authority passed away at the dawn of his eighth decade, having lived long enough to have been briefly “in touch with” crime writer Martin Edwards, who today is president of the Detection Club. Nigel was, to be sure, one of the last of the true Golden Age crime writers.

The third Mrs. Pym novel, The Street of the Leopard (1936), wherein the author pits against each other in the city of London rival race gangs (sinister Japanese and savage Africans), arguably is the nadir of the Mrs. Pym series, though Torquemada deemed this installment a “considerable improvement” over the first two. “It’s more impressive than a [Sydney] Horler shocker!” cries a self-aware character in a meta moment of the mad goings-on in the book. Throughout the tale Mrs. Pym’s penchant for racist invective, her ludicrous hand-to-hand fisticuffs with crooks, and her granted demand for unchecked State of Emergency police power (including use of the third degree) to combat the gangs surely did not appeal to liberal-minded readers, like Howard Spring, literary critic at the London Evening Standard, who tore the book to shreds like a malefic Leopard gangster:

This is a first-rate example of those books which cause a reader with a grain of intelligence to distrust and dislike the whole class to which they belong. It is stuff and nonsense from beginning to end: a piling-up of gross, distorted incidents which the author has no skill to make even superficially probable…perhaps the most ridiculous “great detective” of the many candidates for that title: these are the means which the author uses in pursuit of “thrills” that never get through the laughter induced in every chapter by the crudity of his methods.

On the other hand, some reviewers loved the lavish mayhem that Spring loathed. “African savagery is pitted against Oriental cruelty in a feud which leaves a trail of death,” is how an enthralled Australian reviewer with the Broken Hill Barrier Miner put it, after having stayed up at night to finish the tale in one reading. This besotted man even deemed Mrs. Pym a “likeable character.”

Nigel Morland wrote so many different series (mostly short-lived, outside of Mrs. Pym and a stand-in, the umbrella-clutching Inspector McMurdo, who appeared in nine Morland novels between 1948 and 1959) that one would think there is bound to be something somewhere in his crime canon to appeal to everyone. There are even books, the writing of which perhaps Torquemada influenced, which more closely approximate my idea of classical detection. (e.g., Nigel’s John Donavan, Norman Forrest and Neal Shepherd mysteries published between 1937 and 1939). One thing is beyond doubt, however: Nigel Morland had a fascinating life experience and family background, which in theory should have made for interesting books. However, Nigel deliberately obscured his own past, being in his personal as well as his writing life a man of many aliases. Let us now investigate further.

Part One: Nigel Morland’s Hidden Past

Nigel Morland was born Carl van Biene in London in 1905, not long after the death of Queen Victoria, and would reach adulthood in an era that the great lady would not have recognized. His parents were Benoit van Biene, a musician, and Gertrude Brown, the daughter of a civil servant. Eighteen-year-old Gertrude married twenty-four-year-old Benoit, or Benjamin as he came to be known, in early 1905, the year Edgar Wallace published The Four Just Men; Carl first glimpsed light a few months later. In 1911 the youngster was residing with his mother at an attractive villa at 42 Church Lane, Tooting, South London. Gertrude claimed she was still married, but Benjamin in fact lived apart from his family and maintained that he was single.

Benjamin’s parents were Jews named Ezechiel Van Biene, who went by the name Auguste, and Rachel Cohen de Solla. The son of a Dutch actor, Auguste van Biene (1849-1913) came to London as a teenager and survived as a street musician before finding success as a stage concert cellist. His composition The Broken Melody became a “pop” standard of Victorian/Edwardian England, with Auguste himself performing it over six thousand times. If it ain’t broke don’t fix it! Or perhaps we should say in this case, if it’s broken, don’t repair it.

In London in 1871 Auguste married Rachel Cohen de Solla (1851-1922), who came of a distinguished Jewish family of Dutch—and before that Iberian and Babylonian—extraction. Her father, Jacob Mozes Cohen de Solla (1808-1883), was an immigrant clockmaker who married Sarah Israel de Vieyra (1813-1873) and with her had ten children, seven sons and three daughters. Son Benjamin followed his father’s career path as a clockmaker and David became a glass importer, but the other sons—Maurice, Henri, Isidore, Abraham and Raphael—all were concert singers and composers of note in their day. The youngest son, Raphael, was a celebrated “boy tenor” who died on tour before he reached the age of thirty and is buried in Philadelphia.

Thus, it is no wonder that sister Rachel married a musician and composer (and quite a distinguished one too), although the marriage, which produced five children—Joseph (a schoolmaster), Eva, Emanuel, Benoit (Benjamin), Jacob—had its rough passages and finally foundered on the rocks of illicit amor. Writes Michael Kilgarrif amusingly in his entry on Auguste van Biene in Sing One of the Old Songs: A Guide to Popular Song 1860-1920:

Discovered by Michael da Costa playing cello in the street and given job playing in Covent Garden opera orchestra. Became musical director at the Gaiety. Went on Halls with dramatic musical sketches, one of which, The Broken Melody, ended with him dying over his cello as the curtain fell. On Thursday, 23 January 1913, at the Brighton Hippodrome, with exquisite timing, he actually did die as the curtain fell.

His great-grandson, the actor Roland MacLeod, to whom I am indebted for this information, also tells me that Auguste “spread his image about a bit” and that a letter from Bransby Williams said: “Whenever I was on the bill with Van Biene he always seemed to have a different Mrs. Van Biene with him.”

Rachel divorced the philandering Auguste, who around 1893 married Clare Lena Burnie (1876-1955), who was twenty-seven years younger than he and had been born in Hong Kong, the daughter of solicitor Alfred Burnie. With Lena he fathered six more children: Eileen, Karl, Olga, Violet, Marjorie and Derek, the latter of whom, three years younger than his half-nephew Carl van Biene, ended up dying in California in the 1990s. After Auguste’s death in 1913, Lena moved with part of her brood to the United States, settling at an apartment at 112 Haven Avenue in Manhattan; she died at Freehold, New Jersey, just shy of ninety.

Getting back to Auguste’s first wife, Rachel de Solla, we find that through the de Sollas, the young man who became “Nigel Morland” was descended from the prominent Levi Maduro family of the Dutch colony of Curacao, part of the Lesser Antilles island chain in the Caribbean. Her paternal great-grandfather Solomon Aaron Cohen de Solla married Rachel Levi Maduro of Curacao, who came from a wealthy shipping family. Through the Levi Maduros Nigel Morland was descended from Samuel ha-Levi (c.1320-1360), treasurer to Pedro I, “the Cruel,” of Castile, who ultimately had Samuel tortured to death to discover just where his treasure was. (Tip: Never work for a monarch whose handle is “the Cruel.”)

Samuel ha-Levi was responsible for the construction of the beautiful El Transito Synagogue in Toledo, which miraculously survives today. Another relative from those days was burned at the stake during the Inquisition for secretly practicing Judaism. Another of Nigel’s lines traces back to the Ibn Yahya family of Portugal, the progenitors of which migrated from Babylonia to the Iberian Peninsula in the eleventh century.

Nigel’s family lineage makes him, along with his contemporary thriller writer Jefferson Farjeon, one of the most certifiably “Jewish” of British Golden Age crime novelists (not the most ethnically and racially diverse group of people in history, to be sure, though there was also Leslie Charteris, yet another British thriller writer, who had a Chinese father). Nigel’s grandmother Rachel had come from one of those ancient, “pure-blooded” Jewish lines that crime writer Anthony Berkeley’s sleuth Roger Sheringham had praised in his detective novel The Silk Stocking Murders (1928), though his own blood was “hybrid,” to use Roger’s terminology. Nigel also was unique among British Golden Age crime writers in having had relatives who were murdered in Nazi extermination camps like Auschwitz, the Nazis not valuing, as Roger professed to, pure Jewish blood.

Like so many of his ancestors, Nigel at a young age travelled far abroad. (Antisemitic Soviet propagandists might have called him a “rootless cosmopolitan.”) In 1922, when he was only seventeen, Nigel departed England for the great city of Shanghai, China, where he claimed he worked for several years as a journalist for the Shanghai Mercury. The next year, according to his account, he published his first crime tale, The Sibilant Whisper. After that came Miscellanea, a book of verse, and Ragged Tales, a short story collection, as well as “The Thousandth Man,” a single story in a volume of short fiction published by the Shanghai Short Story Club.

After leaving China, Nigel claimed, he resided for a few years in the United States and published fiction under pseudonyms, for which he had a great penchant, in American pulp magazines, producing, he later estimated, thirty to fifty thousand words a week. (Whatever you think of the quality of Morland’s crime writing, there is certainly a lot of it.) He also claims that he ghosted show business memoirs for industry names and wrote for Movie Day and the Hearst newspaper chain.

For a time after his return to England in the late 1920s, Nigel, as briefly mentioned above, supposedly served as Edgar Wallace’s secretary—a most important position, as Wallace tasked his secretaries with typing his novels, which he reeled off at racing speed into a Dictaphone. This employment, if Nigel actually ever held it, changed the course of the young man’s life, by focusing it on the writing of crime fiction. After Wallace died the path to the shocker king succession lay wide open, though not uncontested, and Morland advanced into the breach with Mrs. Pym barreling along, like a member of the Praetorian crime guard, at his side.

In the early 1930s Nigel collaborated with Peggy Mabel Barwell, a young woman from a wealthy family, on Cachexia, a book of prose-poems, and several volumes of books for children, including The Goofus Man and Mary! The Story of the Magdalene; both of the latter books were illustrated as well by Peggy, a talented woodcut artist. During this time Peggy resided at one of her family’s homes, The Red Cottage, Waltham St. Lawrence, Berkshire, while Nigel stayed eight miles away at The Green Cottage, Henley on Thames, Oxfordshire—doubtlessly a most convenient arrangement.

Nigel and Peggy wed in 1932, when Nigel was twenty-seven and Peggy twenty-three, but their marriage did not survive the Second World War. In 1943 Nigel was named as the adulterous party in the uncontested judicial separation suit of actor Hartley Powers (perhaps best known for playing Sylvester Kee, the rival to the affections of Michael Redgrave’s ventriloquist’s dummy in the final story in the English horror anthology Dead of Night) against his wife, Iris Leslie Powers, an event which reveals the bloom was off the rose of Nigel and Peggy’s lawful union. (Powers obtained a full divorce the next year.) Peggy married another man in 1951, while Nigel for his part wed three more times, fathering a son by his second wife, Pamela Hunnex, whom he wed in 1947. Pamela was twenty years younger than he, suggesting that Nigel followed in his paternal grandfather’s and father’s footsteps in being attracted to young women. Which perhaps explains some of his later books with Tallis Press.

Before the couple divorced, Peggy, while residing with Nigel at a flat in Shepherds House on Shepherd Street in Mayfair (Nigel probably derived his pseudonym Neal Shepherd from this address), co-wrote with her spouse and another man the screenplay for Mrs. Pym of Scotland Yard (1940), an entertaining B-film version of Nigel Morland’s mystery The Clue in the Mirror (1938). As Mrs. Pym the actress Mary Clare, a fine supporting player in the Alfred Hitchcock movies Young and Innocent and The Lady Vanishes, did a commendable job of making the beastly Mrs. Pym not only human but rather bearable, actually. “She is the perfect Mrs. Pym,” a delighted Nigel declared to Manchester Evening News columnist George Grafton-Green in July 1939, when he was serving as an advisor to the film. “I have never seen a character come to life like it before. It is almost uncanny.” The film was planned as the first in a series of Mrs. Pym B-mysteries (Nigel claimed he had already written three scripts), but although the film received good reviews, the series never in fact materialized.

Peggy Barwell was one of three daughters of Augustus Leycester Barwell (of “The Tower,” Ascot), an executive with James Shoolbred & Co., a prominent London furniture store. She grew up as a young girl at The Tower, quite a prosperous household, with six live-in house servants: a children’s nurse, under nurse, house maid, cook, parlour maid and kitchen maid. Years earlier, on the eve of the Great War, Peggy’s handsome older brother, Frederick Leycester Barwell, a golden boy graduate of Malvern College, at the age of nineteen was set to enter Pembroke College, Cambridge University when the shooting at Sarajevo took place, with its fatal results for millions, including Frederick, who promptly volunteered for martial service.

The young man served first with the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, seeing much action in the event. He was finally invalided out in September 1916 with a wound in the knee. There were other things wrong with the young man as well, it seems, according to his physician’s report: ‘In addition he is suffering from exhaustion neurosis brought on by 15 months continuous & arduous active service. At Gommecourt on July 21st his battalion was wiped out, only 150 men remaining after an attack on the German trenches. He has been suffering from diarrhea, palpitations, headaches, exhaustion, dyspepsia, & insomnia & is subject at times to attacks of nervousness.”

In 1917 the resilient Frederick joined the Royal Air Force, but he was shot down and killed, not long after he completed his training, during an aerial reconnaissance on April 29th. It has long been stated that he was fatally dispatched by German pilot Manfred von Richthofen, aka the Red Baron, but this claim has been disputed. I suppose it makes a more glorious end to have been sacrificed to the Red Baron’s death cult.

Not long after the Great War, in which he was too young to have served, Nigel Morland distanced himself from his Jewish forbears, changing his name from what must have been deemed the “foreign sounding” Carl van Biene (Carl Peterson was the name of Bulldog Drummond’s German archnemesis in the Sapper novels), first to Nigel van Biene and then to the impeccably English-sounding Nigel Morland. To be sure, it was not a great time to be known as a Jew in much of the world. How much easier to slip into the very pleasant, “English” world of the Leycester Barwells.

When Nigel came to Shanghai in 1923, the magnificent classical revival Ohel Rachel Synagogue had only recently been completed. Construction had started at the instigation of the fabulously wealthy Sir Jacob Elias Sassoon, Baronet of Bombay, in honor of his late wife, but he had passed away before it was completed in all of its neoclassical glory. During the Second World War, when the forces of Imperial Japan occupied Shanghai, the city’s thousands of Jews were herded into the Shanghai Ghetto and the grand house of worship was converted into a stable. In the aftermath of the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, the synagogue was closed; and by 1956 almost all of the Jews had left the city, never to return. During the Cultural Revolution, the magnificent building was used as a warehouse. In the last two decades, however some restoration efforts happily have been made to the structure, and today it makes a most imposing sight indeed. Then American First Lady Hillary Clinton visited the house of worship in the 1990s, when relations between China and the US were thawing.

Nigel seems to have had little interest in his own Jewish heritage and appears not to have been raised in the faith, having been brought by his presumably Christian mother. What he does seem to have taken seriously is not so much his crime fiction but his researches into true crime. In 1939 he rather grandly listed his occupations as “scientific criminological expert,” as well as “author and journalist.” Doubtless he would have been pleased to have become a member of the UK’s prestigious Detection Club, but such was not to be.

In 1953 mystery writer Anthony Gilbert, a Detection Club member of long standing, met Nigel, who up until then had been, she asserted in a letter to club president Dorothy L. Sayers, “nothing but a name to me.” Despite this lack of familiarity, Gilbert deemed the handsome and ingratiating Nigel a plausible candidate for admission to the club, which after a sad wartime and postwar depletion, stood desperately in need of new, relatively youthful and energetic members. Nigel, observed the appraising Gilbert, was “young—I should say forty—and very active.” (Actually, Morland was forty-eight, making Gilbert’s appraisal a testament to his youthful looks and perhaps the fifty-four-year-old’s admiring eyes.)

Gilbert divulged to Sayers that in her chat with Nigel the younger author had displayed “great interest in the Detection Club” and she speculated that he “would probably jump at the chance of becoming a member.” Sayers, however, seemed unimpressed: “Afraid I know nothing of Nigel Morland,” she declared shortly. Back in the Thirties Milward Kennedy, another active Detection Club member and the immediate successor to Sayers as the Sunday Times’ crime fiction reviewer, had been one of Mrs. Pym’s newspaper detractors, scathingly dismissing Nigel’s The Clue in the Mirror as “not a detective story but a tale of mystery…the kind of thing which Edgar Wallace did infinitely better.”

Nigel Morland never became a member of the Detection Club, though I do not know on what basis the members failed to act on him. Julian Symons had been accepted two years earlier, forcing some of the members, Christianna Brand later sardonically recalled, to have to swallow, for the first time in their lives, their habitual antisemitic remarks. But even had Nigel’s being partially Jewish been something that would have been a problem with some Club members, it is by no means clear that anyone would have known he had any Jewish ancestry in the first place.

Perhaps the members simply felt, as Milward Kennedy had said, that Nigel’s books, the most recent of which were The Moon Was Made for Murder and Sing a Song of Cyanide, simply did not sufficiently excel, however alliterative the titles may have been, at the fine art of detection—something which the Club still ostensibly demanded of its members; work. Yet times were changing and as an alternative to the Detection Club there was always the vastly less persnickety and judgmental Crime Writers Association, which Nigel Morland that very same year himself would play a major role in founding, along with the even more prolific and popular crime writer John Creasey.

With the populist and democratic Crime Writers Association lay the future of British crime writing; and Nigel Morland—the public face of Carl van Biene, grandson of Auguste van Biene—seems emphatically to have been both a survivor and a man of the people. Often to be the former, it seems, you need to be the latter.

Part Two: A Teller of Tales, Primarily Tall Ones

After the Great War Nigel’s estranged father Benjamin (formerly Benoit) van Biene had his name officially changed to Barton van Biene (new name, new life) and in 1922 he married, presumably legally, another woman, Edith Myra Wesley, like Gertrude a daughter of a civil servant. Unlike his previous union with Gertrude, this second marriage stuck. Barton, as he called himself now, died in 1939 at the age of fifty-eight in the north London suburb of Muswell Hill, leaving in modern worth the modest sum of about 8300 pounds (about 10,300 dollars) to his widow Edith.

What were Nigel and his mother Gertrude doing in these years? Well, according to Nigel, Gertrude became associated sometime around the start of the Great War with famed crime thriller writer Edgar Wallace, in the Twenties the bestselling author in the United Kingdom. The hugely popular crime writer—it is said that in 1928 one out of four books sold in the UK had been authored by Wallace—lived with his wife and children at a flat in swanky Clarence Gate Gardens, next to Regent’s Park in Marlyebone, about six miles due south of where the Van Benoits, mother and son, resided. Frequently, according to Nigel, his mother was present at the Wallaces’ place, often with young Nigel in tow. He later wrote of this experience in a 1981 article, “A Day with Edgar Wallace,” which is referenced in Neil Clark’s biography of the Thriller King. According to Nigel, Gertrude had been employed by Wallace during the latter years of the Great War as a “presiding Mother-Friend-Counsellor-Manager—PRO or what have you.” (This is rather amorphous—What have you, indeed! Perhaps FOE—Friend of Edgar—or hanger-on might have served as well.)

Young Nigel, who then would have been around ten to fourteen years old, thereby spent, according to this account, a great deal of his time at the flat at Clarence Gate Gardens in the company of the Great Man, whom he idolized. He even, so his story goes, had his own key to the flat. According to Nigel, Wallace familiarly called him “Niggie” and bought him an expensive scooter at Harrods when the poor lad was convalescing from an illness.

But where exactly does Nigel being Edgar Wallace’s secretary come into all this? Presumably Wallace did not hire adolescent boy secretaries. To be sure, his longtime male secretary, Robert George Curtis (1889-1936), who typed all of Wallace’s dictated novels, had joined the armed forces in 1915, when Nigel was ten. However, Curtis’ replacement was eighteen-year-old Violet Ethel King (1896-1933), a brunette-bobbed daughter of a Battersea solicitor and newly-minted secretarial college graduate. She remained in the position until Curtis returned from the war in 1919. Two years later, by the by, the not so shrinking Violet became the second wife of Wallace, who was over two decades older than she.

Robert Curtis stayed with Wallace for the rest of the author’s life, and was with him at his death in 1932 in Hollywood, where he had been working on the script for King Kong. Neil Clark does state that Wallace hired a supplementary correspondence secretary, twenty-three-year-old Jenia Reisser, an attractive Russian emigre, but nowhere does he mention Nigel Morland performing in any such capacity. Aside from the redoubtable Curtis, Wallace seems to have been drawn to pretty young women as secretaries.

All I really know about Morland’s whereabouts in the Twenties is that on December 9, 1922, when he was only seventeen, he indeed did embark for China, as he claimed, aboard S. S. Teiresias, listing his occupation as “printer” and his home address as the not exactly posh 19 Crouch Hill, Stroud Green, London (today the home of Max’s Sandwich Shop.) Nigel spent 1923 in Shanghai, where as previously mentioned he claimed to have worked as a journalist for the Shanghai Mercury and where he published his first fiction. He claimed to have spent some time in the United States too, on the West Coast. Certainly, Nigel’s books evince familiarity with the good old U. S. of A. By 1930, however, he was back in the mother country, where he soon made the acquaintance of the well-off and artistically inclined Peggy Barwell. For a couple of years, the two co-authored several non-criminous, small beer books before marrying in 1932, the same year Edgar Wallace died.

So just when it was that Nigel might have been employed as Wallace’s secretary seems unclear. Perhaps Nigel used to fetch cups of sweet tea for the Great Man, a notoriously copious imbiber, back during the Great War? However, it is rather a long distance between Edgar Wallace’s private secretary and his chai wallah.

I do not have a copy of The Moon Murders, the first of Nigel Morland’s Mrs. Pym mysteries, which when it was published in 1935, when Nigel was twenty-nine, made his name in the crime fiction genre, however equivocally. From internet images it is apparent that there is nothing said on the jacket about Edgar Wallace, though the symbol on said jacket, which Morland used for the rest of his life as a mystery writer, bears a marked and rather brazen resemblance to Wallace’s famous crimson circle insignia. In his review of the novel, blogger John Norris states that Morland dedicated the book to the memory of Wallace and credited Wallace with inspiring the character of Mrs. Pym.

That notwithstanding, the real push for Nigel Morland as the “new Edgar Wallace” seems to have come with the 1937 US publication of a Mrs. Pym novel, The Clue of the Bricklayer’s Aunt, a jacketed copy of which I own. To an English crime writer, snagging American book sales was a very big deal indeed. On Aunt‘s jacket the American publisher certainly did not hold back on the ballyhoo: “Introducing a Mystery Writer whom Edgar Wallace nominated as his Literary Successor….Edgar Wallace, before he died, trained a young man to follow in his footsteps, and furthermore he created and gave to the young man the germ of a character, ‘Mrs. Pym of the C. I. D.’”

This is getting pretty florid and fancy, yet however exaggerated these claims may be (and I think they were), Nigel’s mother Gertrude, to whom he dedicated Street of the Leopard, had at least one verifiable connection to Edgar Wallace though her second husband Edward Ashley Lomax, a forty-two-year-old former rancher and “gentleman of independent means” who owned Grouville Court on the Isle of Jersey. A year after his marriage to Gertrude in 1927, Lomax claimed the copyright to the 1928 Edgar Wallace crime thriller play The Man Who Changed His Name. (With such a title this play could have been about Nigel Morland and his forbears.) Lomax died in 1946, incidentally, leaving Gertrude with an inheritance valued in modern worth at about 1.5 million pounds (1.8 million dollars). It would seem that she had come up quite a bit in the world since her marriage to Benoit/Benjamin/Barton van Biene.

The play, which was not one of Wallace’s more successful ones, was later adapted as a novel by Robert Curtis, who in the brief time between Edgar Wallace’s death and his own untimely demise strove to grab Wallace’s crown by publishing thrillers based on the Great Man’s plays and film scenarios, the last shreds of fiction with actual links to Wallace’s own imagination. I think it is significant that Nigel advanced the more grandiose claims about his relationship with Wallace only after the death of (1) Wallace’s second wife (his first wife had already predeceased him) and (2) his actual private secretary, Robert Curtis. Indeed, if you want to get bookish, the untimely deaths of Mrs. Wallace (age 37) and the private secretary (age 47), following so rapidly on the heels of the Master himself (age 56) would make a great plot for a Golden Age murder mystery. It is rather like something out of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple detective novel A Pocket Full of Rye. Whodunit? I’m looking at you, Nigel! (Just kidding.)

There were three older Wallace children from Edgar’s first marriage, who were roughly Nigel’s own age, but the primary heir of the Wallace estate—which when Wallace died consisted mostly of debts incurred from his lavish spending, though this was soon turned around from book sales—was Wallace’s beloved, pampered daughter from his second marriage, Penelope, who was only eight years old when her father died. Thus, Nigel may have believed that he was free to aggrandize himself vis-à-vis Wallace pretty much unchecked. Would Nigel have done such a thing? The short answer seems to be heck, yeah, he sure would have.

Decades after Wallace’s death, in the mid-Sixties, Nigel had taken over the editorship of Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine and was promising that he had an Edgar Wallace biography in the works, though in fact no such thing was ever published by him. However, Nigel’s takeover of the editorship of EWMM was not accomplished without leaving bitter feelings in its wake on the part of the previous editor. EWMM was started in 1964 by twenty-one-year-old Keith Chapman, former editorial assistant of the Sexton Blake Library. For a nominal fee the Edgar Wallace family allowed him the use of the Great Man’s name for a crime fiction magazine, and soon EWMM was off and running—but not very far.

In a few months the company that owned the magazine found itself on a precarious financial footing and the Wallace family stepped in, sacking Chapman, who was left quite irate about the whole thing. Forty-four years later, he complained about the affair at the website Mystery*File, laying emphasis on what he deemed Nigel’s mendacious conduct:

I have letters on file from Nigel Morland ostensibly offering me support, telling me how “impressed” he was [with EWMM], how it was “first class” and “excellent.” But many [of these letters] were written when he must at least have had an eye on taking over my role.

“Dear Keith, I had the new issue, and really do think you are doing it well. You’ve set a standard, and that is a high one. So far you seem to better it a little with each issue, which, after all, is the heart of all really good editing.

Congratulations. Every good wish, Yours, Nigel.”

Two months after Morland wrote this missive, Chapman was fired and replaced by his professed admirer, whom, Chapman recalled, “I was told by Penelope Wallace and her husband…was older and more experienced than me, and therefore would make a better job of the magazine.” Chapman claimed that many crime writers and contributors to EWMM supported him during this tough time, including T.C.H. Jacobs, another Thirties pretender to Wallace’s throne (he had debuted back in 1930 with The Terror of Torlands), who had been a prime mover, like Morland, in the formation of the Crime Writers Association. Jacobs wrote Chapman the following commiserating message: “Their choice of an editor astonishes me. I have known Morland for many years and am unaware he has ever had any editorial experience. But I do know that he has always claimed some connections with the Wallace family. Maybe it is true. I don’t know. He is certainly older than you, sixty.”

Chapman had been at the helm of his brainchild EWMM for merely four months. Nigel Morland would only make it for two and a half additional years before the magazine failed in 1967. Chapman saw it as poetic justice.

“He has always claimed some connections with the Wallace family. Maybe it is true. I don’t know.” And there you have it, in the form of T.C.H. Jacob’s words, in a nutshell. Jacobs had known Nigel for years as a colleague and presumably a friend of sorts, but he did not know whether what Nigel had said, over and over and over again, about his connection to Edgar Wallace could be believed. Not much of an endorsement of Nigel’s veracity.

Other people have expressed similar doubts about Nigel’s truthfulness. In the large community of devotees of the Jack the Ripper murders, known as Ripperologists, Nigel’s name, it does not seem an exaggeration to say, is mud. Why is this? Because in the community he is generally deemed a liar or, shall we say more politely, a fabulist or fantasist.

In Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates (2006), Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow write that Nigel, a “self-proclaimed criminologist,” was one of the Ripper writers who had a habit of “inventing tales that posed as factual events.” In 1978 Nigel wrote the introduction to Frank Spiering’s 1978 book Prince Jack: The True Story of Jack the Ripper, in which Spiering advanced the theory that Queen Victoria’s grandson Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence (aka Prince Eddy) was guilty of the Ripper murders. Nigel claimed in his introduction to the book that as a youngster he had become interested in the Ripper story when no less a personage than Arthur Conan Doyle told young Nigel that the identity of the Ripper belonged “somewhere in the upper stratum.”

As Nigel put it decades later: “I was interested in the Ripper in a purely academic way when I was a youngster, intrigued by a mention to me by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Conan Doyle remarked to me that the Ripper was ‘somewhere in the upper stratum,’ but he would never enlarge upon that statement.” Had Sir Arthur just happened to come to over to have tea with Edgar Wallace at Clarence Gate Gardens when young Nigel was there, taking a breather from motor scootering? Truthfully, I do not know that Wallace and Doyle ever even really met. On an internet message board Stewart P. Evans has commented humorously that the late criminologist Richard Whittington-Egan “knew Morland and said that if you mentioned Dr. Crippen to [him], Morland would then tell you how he sat on Crippen’s knee as a child.”

And, sure enough, Morland did tell people he had sat on Crippen’s knee as a child. His nanny just happened to have taken him on a visit to the Crippens, you see, and…. Tellingly, one of the books Nigel published with Peggy Barwell was titled, People We Have Never Met: A Book of Superficial Cameos (1931).

“Morland had met just about anyone who was anybody in his day,” observe Evans and Rumbelow sarcastically in their book, before they dig into Nigel’s claim of having in the Twenties interviewed Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline, one of the lead investigators of the Ripper case (this around the time he was running round with Wallace and Doyle). Evans and Rumbelow view dubiously indeed Nigel’s account of interviewing the elderly retired policeman in the early 1920s, when the teenager was “home on leave from his job as a crime reporter on a newspaper in Shanghai.” According to Morland,” write the authors:

Abberline said, “I cannot reveal anything except this—of course we knew who he was, one of the highest in the land.” This alleged statement flies in the face of everything that Abberline had been reported to have reliably said about the case in the past. And why? The answer must be obvious. Morland had made the whole thing up, but the damage was done. This alleged statement by Abberline is now often quoted.

I think it is clear that with Nigel’s divulgences an unhealthy amount of grains of salt must be taken. Nigel also said he was on terms of friendship with American FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and he self-servingly dedicated the American edition of The Corpse on the Flying Trapeze to the top G-Man. Perhaps had Nigel lived a little longer, until the claim that Hoover was a cross-dresser surfaced in 1993, he might have confirmed to his public that while living in the US in the 1920s he once had helped fit the Director into a dress.

Nigel Morland was a handsome man and he was said to have been quite a charming raconteur. On meeting crime writer Anthony Gilbert in 1953, for example, he clearly rather impressed her. Of course, the cynical will suspect that the of-a-certain-age “spinster” Gilbert was, shall we say, susceptible, having already unrequitedly fallen, according to catty Christianna Brand, for her Detection Club colleague John Dickson Carr. However, there seems to be no question that Nigel had an exceptionally persuasive personality.

It seems to me that Nigel Morland likely was a serial liar, in some ways resembling, in a far more limited manner, sociopathic conman and mystery plagiarizer Maurice Balk, about whom I have previously written at Crimereads. Though unlike Balk, Nigel had some actual writing ability and his lies, if lies they indeed were, did no harm to anyone personally, unless you count a mendacious author gulling people into buying his books by making himself seem more exciting than he actually was (though admittedly I can see how his treatment of Keith Chapman was hurtful to the latter man). Yet even if, as seems likely, many of Nigel’s truths were lies, he is still an intriguing person, in part precisely because of those lies. In life, as in fiction, brazen scallawaggery always seems more fascinating than modest goodness.

Postscript: Fabulist’s Ball; or, A Lively Chat with Mr. Morland

In 1978, Nigel Morland, now a venerable seventy-three, sat down for an interview with freelance writer Pearl Gold Aldrich, during which he wove, like a kind of modern-day, male Scheherazade, a tale of the seemingly 1001 famous people he had known. Aldrich, unquestionably one thoroughly tough cookie, had served in the US Marine Corps during World War Two and was an officer in the WACS from 1949 to 1955. She later became a member of the English faculty at Frostburg State University and she belonged to MENSA and Sisters in Crime. A great mystery fan, she published articles in both The Armchair Detective and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. She gathered the accounts given her by Nigel, who seemingly possessed an uncanny knack for meeting famous—or more often infamous—people, into an article, “Nigel Morland—Fifty Years of Crime Writing,” that was published two years later in 1980 in Allen J. Hubin’s and Otto Penzler’s The Armchair Detective [TAD], a primary source of information about classic crime writing in those dim, distant days before blogs.

Was Pearl Aldrich actually taken in Morland’s tall tales? It seems hard to believe, but all we have to go by is the balderdash she wrote down, unquestioned, in her article. According to Aldrich, writing it all down straight from the horse’s mouth, as it were, Nigel was a man whose nurse had her medicine mixed up by Dr. Crippen; who found himself lined up at a bar one afternoon with the great detective, Fabian of Scotland Yard; who met John George Haigh, who became the “acid bath murderer”; Neville Heath, who became a sadistic murderer, ripping his victims to death, and his first victim, Margery Gardiner, whom Heath had only just met; who lived next door to Heath’s second victim; whose American aunt introduced him to Madeleine Smith and Lizzie Borden’s sister; and who grew up practically at Edgar Wallace’s knee….

This is a striking roster indeed, and it is only the first paragraph of the article. But, wait, as the commercials say, there’s more. As told above, Nigel went to Shanghai in late 1922, when he was seventeen. (This is documented.) There he apparently worked as a “cub reporter” for several years. This gets embellished in the TAD article, where Aldrich states that Morland “set off for China alone at 14 to become a newspaper reporter.” That alone would have set off alarm bells for this reporter, but it gets better yet. Quoting Morland in the article:

Then in 1919 Mother had to go to China on a visit and, when she was out there, I suddenly decided I would like to go there too. So I wrote, Mother agreed, but I missed the boat and went on the next one. In the meantime, she started for England, and we met in the Red Sea…. We had established contact by wireless, and the captains brought the ships as close as they dared. I saw her from the deck of the ship as we passed, and we managed to wave to each other in the Red Sea as we went through.

I was expecting Nigel to divulge that Moses popped up at that point and obligingly parted the Red Sea so that mother and son could get out of the boats and have a nice chat together, perhaps a cuppa too, but maybe Nigel saved that revelation for later, along with that time when he helped Moses out on that mountain when he got stuck on the ninth commandment (you know, the one about not bearing false witness).

In China, where Nigel says he was for the years 1923-25, he accompanied a sergeant from the Shanghai Municipal Police Force on his investigation of a hotel crime scene. He—well, let Nigel tell it:

The officer was a big, tough, red-headed, very rough looking man, what I call a knock-about-third-degree-type of policeman. As we went into this hotel, there were a few people in the lobby, including a little, round-faced, chubby Chinese with some friends. He bowed and smiled. The policeman went ahead, and as he did so, the little Chinese stepped in his way. The sergeant pushed him violently aside. Unlike most Chinese, the little fellow came back and started arguing, and the sergeant, whose face was growing red, and I could see was beginning to burn up with temper, opened the holster of his revolver and started pulling it out.

I was scared stiff because I thought he was going to shoot the little Chinese, and I sort of pulled his arm and said, “Look, let’s get upstairs. I don’t want to get involved in anything.” He cursed and swore at the Chinese, but we went upstairs.

I later learned who he was. His name was Mao Tse Tung. I saw him several times afterward, and he always bowed and smiled at me. I’ve frequently wondered what would have been to story of China if that sergeant had shot him.

What were the odds? So to Nigel Morland we owe the Cultural Revolution. Thanks, Nigel!

Nigel also told Aldrich that he helped with rescue work in Japan following the devastating 1923 earthquake. Indeed, he was so busy helping out he forgot to file a story with his paper. But in 1925 the newspaper stories which were filed by Nigel, who termed himself a “young, brash idealist” warning the world about the “yellow peril, the Japanese”—got him placed at spot #3 on the “Japanese death list.” (Who were #1 and #2, I wonder?) So, he had to take a fast boat back to Britain. “[A] few years later the Japanese invaded China and took over Shanghai,” Nigel reflected. “I could have been shot, if not worse, for my virulent anti-Japanese writing.” Not bad for a twenty-year-old cub reporter!

Nigel’s friend Arthur Conan Doyle goes unmentioned, amazingly, in this article, as does Nigel’s claim, made elsewhere on several occasions, that during a trip home in 1923 he interviewed one of the investigators of the Jack the Ripper murders, who implicitly implicated Queen Victoria’s grandson Prince Eddy. However, there is quite a bit about Edgar Wallace, Nigel’s alleged mentor. Here it is claimed by Nigel that he first met Edgar Wallace in 1915 at the age of ten, in company with his mother Gertrude, who “became the closest friend of the [Wallace] family until Edgar died.”

“[Mother] became a kind of general factotum, helpmeet, housemother, and everything, remaining so even after Ivy and Edgar divorced and Edgar remarried,” Nigel explains. “She was great friends with Ivy after the divorce, too, because she was a kind of middle ground to which they all turned. When the second Mrs. Wallace died, she made mother executor of the estate. That’s how close they were.”

In fact, it was Edward Ashley Lomax, along with theatrical producer Sydney Edmonds Linnit, who served as co-executors of the estate of Ethel Violet Wallace after she died in 1933. Six years earlier, it will be recalled, Lomax had wed Nigel’s mother. Thus, there is a connection of a sort, though it was through the agency of Nigel’s mother’s second husband.

Violet, incidentally, left an estate valued at a nearly a half million pounds in today’s worth. The first Mrs. Wallace, Ivy, had persuaded her husband to divorce her in 1919 so that she could marry a Belgian refugee named Leon, whom after the divorce she found was already married. (Ivy was cited as the offending party, though in fact Edgar was having it off with both his secretary, the soon-to-be second Mrs. Wallace, and a mistress named Daisy.) Ivy, writes Wallace biographer Neil Clark, was left high and dry by Leon and “was to go rapidly downhill.” She died in 1926, leaving an estate worth just 23,000 pounds in modern value. It is unclear where “housemother” Gertrude, Nigel’s mother, exactly fit into all this tragedy, which was does not reflect particularly well on Nigel’s supposed mentor.

Nigel says he returned to England from China in 1925—his time in the US goes unmentioned here—and what did he do first? Why, visit Edgar Wallace, naturally:

When I got back to England, I dumped all this stuff, all this fiction, on Edgar Wallace’s lap, as it were, and he looked through some of the stories and said, “Nigel, this is dreadful. You’re writing yourself out before you’ve even started.” He said, “I’m going to impose a penance on you. You just don’t write any more for a year or two and, in that time, you read and think, read and think, but you write not a single word. Give yourself a chance to mature, to catch your breath, and to learn something about style. You are a born crime writer, but what you’ve got to do in the time you’ve got this kind of sabbatical is think about the detective….

Now, let’s think about the detective. What shall we have? I’ve just been reading a book about a Cromwellian soldier named Pym, John Pym. I like that name. Think about that. We’ll call him Pym. No, we won’t! We won’t! We’ve got a better idea.” Incidentally, Edgar was always fond of using the royal ‘we.’ He said what we’ll do is to change the sex to a woman. “Let’s think of a woman detective, a tough, hard-boiled woman, not a private detective, but a real detective of Scotland Yard. Take that away and brood over it, and that figure will mature in your mind. When you come to write that book, you’ll find it will come out like nobody’s business.”

And a few years later, that’s just what I did. I wrote the book and sent it to Desmond Flower of Cassell…. Flower was on the phone in twenty-four hours, saying he’d buy it.

This is the most detailed version of Nigel’s claim that Edgar Wallace inspired Mrs. Pym. Indeed, he is essentially claiming that Edgar created Mrs. Pym. One queer part of this claim is that this self-serving conversation with the Master (“You are a born crime writer”) allegedly took place in 1925, yet the first Mrs. Pym book, The Moon Murders, was not published until 1935, a decade later. That is rather a long sabbatical. Interestingly, it was not until after the deaths of both Edgar Wallace and Edgar’s first and second wives (the latter of whom made Nigel’s stepfather co-executor of her estate) that Mrs. Pym appeared in print, along with all of Nigel’s tales about his close connections to the Wallace family. There was of course no one around then to contradict him.

There are other interesting assertions from Nigel in the article, like the one that he wrote “over 300 novels” (“bestsellers”) and “almost as many factual books.” I have tried but cannot come up with anywhere near that many books by Nigel (the website classiccrimefiction lists seventy-two works of crime fiction and a single mainstream novel), but perhaps he wanted badly to be able to say he had outdone the master, Edgar Wallace, in some respect, even if it was merely a case of quantity over quality.

When Nigel Morland, now eighty years old, passed away in 1986, in the midst of the Tory Age of Thatcher, his obituary, published in minor English newspapers, repeated many of the author’s hoary claims of having met ever so many notable and notorious people, adding to the black list of his personal encounters a certain odd chap by the name of Hitler, about whom the author had warned everyone he could that he “was mad as a hatter.” Had people only listened to Nigel! Though incongruously in 1936 in The Street of the Leopard Nigel had his reporter character Dick Loddon think dismissively of “the eternal nonsensical crisis in European politics” that boringly fills the newspapers, much preferring to this his own screaming banner headline about murderous Asian and African race gangs:

“LONDON IN GRIP OF CRIME WAVE!”