A Remarkable Case of Plagiarism

Fictitious plagiarism figures more than occasionally in Golden Age detective novels, but only a tiny number of Golden Age detective novels are known actually to have been plagiarized. While Raymond Chandler hurled plagiarism accusations at prolific British crime writer James Hadley Chase and it has been suggested by some (me, for example) that Agatha Christie might have drawn inspiration for her classic mystery novel And Then There Were None (1939) from Bruce Manning’s and Gwen Bristow’s The Invisible Host (1930), by far the most egregious known example of plagiarism from the Golden Age of the detective novel is Englishman Don Basil’s mystery Cat and Feather, which was published in 1931 in England by “Philip Earle” and lifted nearly word-for-word from American Roger Scarlett’s The Back Bay Murders, published in the United States by Doubleday, Doran the previous year. In his January 1978 column in the landmark fanzine The Armchair Detective, edited by Allen J. Hubin, noted book collector Edward “Ned” Guymon, who had corresponded about the matter a few years earlier with Dorothy Blair and Evelyn Page, the couple who during the Thirties had written the five “Roger Scarlett” mysteries, dramatically pronounced Don Basil’s Cat and Feather “probably the most glaring piece of plagiarism ever to exist.”

Ned Guymon explained that the Don Basil’s novel did not involve a simple matter of “similarity of character or plot or situation.” Rather, it was a case of a “word for word copy.” “The English characters have different names, English locale has been substituted for American and there are a very few English words used to clarify American terms,” wrote Guymon. “Otherwise this book is a flagrant and larcenous case of plagiarism. You should see it to believe it.”

I have seen a copy of Don Basil’s book (which is extremely rare), and, having seen it, I do indeed believe it. Here are two pairs of matched quotations from the novels that illustrate the breadth and brazenness of Don Basil’s plagiarism:

I had known Kane for many years, but not until some months ago had I been associated with him in one of his cases. On that occasion I had been present, as the family lawyer, at a dinner party which had a fatal ending, and had called Kane, my only friend among the police inspectors of Boston, to my assistance and to that of the Sutton family. His spectacular solution of that case, widely known as the Beacon Hill murders, had put him in the limelight as far as the public was concerned. (The Back Bay Murders)

Article continues after advertisementI had known Richard Kirk Storm for many years, but not until some months ago had I been associated with him in one of his cases. On that occasion I had been present, as the family solicitor, at a dinner which had a fatal ending, and had called Storm, my only friend among officials of Scotland Yard, to my assistance and that of the Stafford family. His spectacular solution of the case widely known as The Bexhill Murder Mystery had put him in the limelight as far as the public was concerned. (Cat and Feather)

Twenty minutes later Kane was propelling me through the doors of Thompson’s Spa.

“Don’t let a murderer get the best of your appetite, Underwood,” he cautioned me, grinning down at my gloomy face, “whatever else he does to you. Here’s an empty counter and an idle handmaiden. Sit down.” He slapped a stool. Without a word I climbed up on it and he sat down beside me. “It’s past eating-time and I know it. We’ll have oyster stew, with flocks of oysters, and, let’s see—for a climax—“ He debated gravely, and then brought out with gusto, “Pumpkin pie.”

I forced a smile. The mention of food gave me no pleasure. “That’s just where you’re wrong,” Kane announced when I explained this to him. “You know,” he looked at me quizzically, “I’d lay a bet that nine out of ten really good murderers lose their appetites right after shooting. And a heavy-eating gumshoe gets them on the hip every time. So forget your troubles.”

Article continues after advertisementHe ordered for us both. When we were served I fished about in my stew with as good grace as I could muster. (The Back Bay Murders)

Twenty minutes later Storm was leading me through the doors of a restaurant. “Don’t let a murderer get the best of your appetite, West,” he cautioned me, grinning down at my gloomy face, “whatever else he does to you. Here’s an empty table and an idle handmaiden. Sit down.”

Without a word we sat down at the marble table….

“It’s past lunch-time, and I know it. We’ll have steak and kidney pie, with stacks of chips, and, let’s see—for a climax—“ He debated gravely, and then brought out with gusto, “College pudding.”

Article continues after advertisementI forced a grim smile. The mention of food brought me no pleasure.

“That’s just where you’re wrong,” Storm announced, when I explained to him. “You know,” he looked at me quizzically, “I’d lay a bet that nine out of ten really good murderers lose their appetites after the murder. So forget your troubles.”

He ordered for us both. When we were served I toyed with my food with as good grace as I could muster. (Cat and Feather)

Aside from changes in paragraph structure and character names (Kane becomes Storm, Underwood West, the Sutton family the Stafford family, the Beacon Hill murders the The Bexhill Murder Mystery), as well as some alterations of Americanisms (police inspectors of Boston becomes officials of Scotland Yard, lawyer solicitor, Thompson’s Spa a restaurant, oyster stew steak and kidney pie, flocks of oysters stacks of chips, pumpkin pie college pudding and fished about in my stew toyed with my food), the text of Cat and Feather is identical to that of The Back Bay Murders all through the book. This really is a remarkable–remarkably egregious–case of plagiarism. Irony is added, as Ned Guymon noted, by the fact that “Don Basil” charmingly dedicated “his” novel “To Basil Holland, who once said, ‘Uncle, please write a detective story for me’.” To this Ned Guymon witheringly commented: “Basil Holland got his detective story all right but his uncle didn’t write it, he copied it.” Nor, in fact, does it appear that young “Basil Holland” ever actually existed.

Don Basil’s perfidy went undetected in the UK, but in the US, where the novel had been picked up for publication by Henry Holt, Cat and Feather was pulled from circulation and “Don Basil” disappeared from the annals of mystery writing, leaving us with the question of just who this devious individual really was. After I posted about this remarkable case of plagiarism five years ago on my blog, The Passing Tramp, percipient British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon identified “Don Basil” as none other than the Cat and Feather’s publisher “Philip Earle,” whose real name, according to Sturgeon, was “Morris Balk.” With this information I have been able to track much of the criminal career of a consummate confidence trickster–surely one of Britain’s most intriguing con men.

Pleased to Meet You, Hope You Guess My Name

Maurice E. Balk (1901-1981) was, as the saying goes, a man of many parts, many of which were doubtlessly attractive on the surface, however repulsive they were beneath it. A survey of the man’s kaleidoscopic criminal career as it unfolded in at least three countries and two continents over three or more decades reveals an ingenious, insinuating man of seemingly no moral conscience who in his destructive wake left a trail of cruelly deceived victims.

Born in London on July 5, 1901, Maurice E. Balk was the son of Leon and Minnie Balk, Russian Jews who around the turn of the nineteenth century migrated to England, where they became naturalized British citizens. Leon Balk, who during the first decade-and-a-half of the twentieth century owned photography studios in the Sussex seaside resorts of Eastbourne and Bexhill-on-Sea, was born around 1873 in the city of Taurage (now part of Lithuania) to David and Jehudith Balk. After moving from Lithuania to England he initially settled in London, where in 1901 he married another native Lithuanian, Minnie Blumenthal, and where two years later Minnie gave birth to Maurice, the couple’s eldest child. By 1904 Leon and Minnie had relocated from London to Eastbourne, where their second son, Phillip, was born. By 1909 the family resided at 23 Sackville Road in Bexhill-on-Sea, where Leon operated a photography studio at 69 Devonshire Road. Leon was doing well enough with his business at this time to employ a single house servant.

It was in 1909 that scandal, in the form of an attractive young woman named Emma Whaley, stalked Leon Balk. That year this unfortunate lady brought a paternity suit against Leon, alleging that he had seduced her at his photography studio, which the previous June she had visited, attired in “light summer costume,” to have her photo taken in bathing dress. After this illicit sexual escapade, according to Emma, Leon had gifted her with presents of jewelry, promised to marry her and fathered a child upon her, only at which point she learned, much to her dismay, that her lover and the father of her child was already married. Despite this scandal, however, the Balks remained in Bexhill-on-Sea for another half-dozen years, Leon even producing another child with his wife. Or could little Bessie Balk, significantly younger than her two brothers, have been Leon’s love child with Emma?

Having left his sex scandal behind him, Leon Balk seems to have passed away during or slightly after the Great War, when he would still have been only in his forties. (Or perhaps he abandoned his wife and family.) Leon’s wife Minnie, who died in London in 1923, having endured her husband’s extramarital fling with Emma, saw her final years further darkened by the activities of her elder son Maurice, who by 1917 had precociously commenced upon, at the age of sixteen, what would prove a rather lengthy career in crime. (Philip and Bessie, on the other hand, became respectable musicians, Philip an orchestral pianist and Bessie a pianoforte soloist and teacher.) In September of that year Maurice, who formerly had been employed as a message boy with J. C. Meacher, a longtime Finsbury pharmacist, was arrested and arraigned before London’s Mansion House Police Court on the charge of obtaining, by means of forged orders purporting to come from his former employer, a quantity of pharmaceutical and photographic goods, as well as first-aid and medical cases, together valued at several hundred pounds, from several London business firms, including Kodak, Ltd, which he then sold to a pair of City businessmen, Henry Peter Kovski, a fancy-goods dealer, and Richard Wilson, a chemist.

Both Kovski and Wilson were charged with receiving stolen property, although the two men claimed that they had been bamboozled by Balk, who at an early age already had become rather an artful fraudster. Koski declared that Balk had represented himself as an American who wanted to get surplus goods “off his hands,” while Wilson, who abjectly proclaimed himself “stupid” for having been duped by the youth, contended that Balk had convinced him that he was selling the goods on behalf of “a friend at Brighton.” Thus was set a lifetime pattern of criminal deception on Balk’s part. He would repeat this modus operandi over and over again.

Maurice Balk pled guilty to the crimes in November but seems to have avoided–or to have served a minimal amount of–jail time, perhaps because of his tender years. By the next year, 1918, Balk, now all of seventeen years old, had ventured into the British film business (or so he claimed), directing, scripting and starring in an alleged crime film, Cheated Vengeance. Only three other cast members for the film are listed in the British Film Catalogue: Doris Vivian Earle, E. James Morrison and Connie Sweet, as well as one co-scripter, H. V. Emery. Like Balk himself, none of these people have any additional film credits listed on the international movie database (imdb). Nor does the film’s production company, Britamer, which would turn up again six years later as the Chicago publisher of a collection of short stories authored by Balk. Was the whole thing just one of Balk’s elaborate grifts, a Potemkin production company, as it were?

Certainly one would like to know something more about this film and the people who were involved with it, particularly actress Doris Vivian Earle, whose surname Balk evidently appropriated for his own use. It is likely that Balk, in his capacity as managing director for the Britamer Film Company, defrauded a number of credulous people, promising them employment after deposits were made with the company. A 1919 letter from Balk to fourteen year old Eugenie Vera Barnes of Birmingham promised to hire the girl at a weekly salary of twenty pounds a week (nearly 1000 pounds today, or about 1200 dollars) after she–or more likely her parents–sent the company a deposit of twenty-five pounds, the latter of which was purportedly to be refunded. A British newspaper naively reported the lucky girl’s great good fortune, which in reality was more likely nothing other than a conman’s artful mirage.

Balk’s venture into filmmaking proved short-lived, for in 1920 he was on his way to the United States, and not to Hollywood. On February 29–the fact that it was a leap year seems appropriate—Balk embarked from Southampton aboard the S. S. New York, destined for Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He gave his occupation as “student” and his “race or people” as Russian, though an official hand wrote “Hebrew” in cursive script over the typed word Russian. For “name and complete address of nearest relative or friend in the country whence alien came” Balk listed his mother, “Mrs. Balk,” and 230 Seven Sisters Road in Finsbury (today the site of Zamzam, a Somalian restaurant). He claimed he was coming to America to join an uncle, Maurice Max Blumenthal, of 433 Liberty Street, Winston-Salem, and that his stay in the US would be of “indefinite” duration.

Both Maurice Blumenthal, a dry goods merchant, and his wife Rose were Jews of Lithuanian descent, like Balk’s parents, and it would appear that Balk was telling the truth for once and that Maurice Blumenthal indeed was Balk’s uncle. (Likely Balk was named after Blumenthal.) Puckishly Balk would later use the name “Morris M. Blumenthal” as one of his criminal aliases. Balk seems quickly to have insinuated himself as a member in good standing of the Jewish community in Winston-Salem, a thriving textiles and tobacco manufacturing center where Jewish immigrants had been locating since the 1880s. Contemporary newspaper accounts list a “Dr. Maurice Balk, a recent arrival from London, England,” as a guest at a “very jolly little party” given in late May of that year by Miss Dora Levy, daughter of Winston-Salem shoe store owner Louis Levy, at her home at 1504 East Third Street. Along with Dora’s friend Miss Bess Horowitz, the ever helpful and ingratiating Balk assisted the hostess with serving refreshments.

Later that year, however, Maurice Balk departed Winston-Salem for New York, where in Manhattan on June 26, 1921 he wed Ruth Krause, the first in his series of loved and left wives. In Manhattan he established an acquaintance with the beloved American poet Edwin Markham (1852-1940), author of the once much-celebrated poem “The Man with the Hoe,” who lived with his third wife in a book-bedecked home on Staten Island. On March 23, 1921, three months before his first marriage, Balk wrote Markham a letter from Boston’s Gordon Bible College, a non-denominational evangelical Christian school that had been founded in 1889, where he evidently had enrolled as a student. In a floridly signed note that accompanied the missive Balk ingratiatingly informed the esteemed man of letters that he had enclosed his own poetry for a forthright evaluation: “I am sending you the first lines I have written. You said you would pull them to pieces for me. Do so, and in so doing please remember that however ‘hard’ you may be in your criticism, my love for you, dear Edwin Markham, will ever remain the same.”

Balk’s acquaintanceship and correspondence with Edwin Markham lasted a couple of years, during which time the young man was carrying on further dubious activity in Canada. On March 18, 1922 Balk wrote the poet from the village of Tusket, in southwestern Nova Scotia, addressing him, as he did in all his letters, as “My dear Edwin Markham.” A wheedling note is detectible underneath the fulsome flattery:

Have you had the opportunity to look over the poems which I sent you last year? I am really anxious to know what you think about them.

There is no living writer, and very few among the dead, whose approbation I should be more glad to earn than yours. I write this to say so.

A book entitled “TO-DAY” is to be published in the course of a month or so, and I have taken the liberty of dedicating it to you.Hoping to hear from you in due course, with best wishes,

Believe me, to be,

My dear Edwin Markham,

Ever your faithful friend,

M. S. Balk

“M. S. Balk” is prominently underlined, while beneath this name is written first “Morris Balk” in lead pencil and then “Maurice” in ink. Balk need not have worried about Markham’s inattention, for on February 25 the flattered poet had sent Balk two pages of criticism, though evidently this had not yet reached the youthful supplicant, whose supposed book of poetry, To-Day, seems never to have appeared in print. Unhappily for Balk, he soon would find himself harried by a more immediately pressing matter. A notice appeared in the November 4, 1922 issue of the church journal The Baptist giving warning to Canadian congregants to take care in any dealings with a certain Maurice E. Balk:

NOTICE

This Is To Inform any person concerned, particularly home mission churches, that one known as Maurice E. Balk, recently in Western Nova Scotia, has no recognized standing as a minister of the United Baptist Convention of the Maritime Provinces. By order E. S. Mason, Cor. Secy., Home Mission Board, Wolfville, Nova Scotia.

With Canadians having turned cold shoulders to him, Maurice Balk returned to New York and pleasant literary chats with Edwin Markham. He also secured himself a new bride, in Manhattan on April 8, 1923 wedding Teresa Trucano, a pretty twenty-four year old opera singer and daughter of an Italian immigrant who had mined copper in Meaderville, Montana, later opening a general store and becoming an Italian consular officer in Butte. In an article about Teresa from a couple of years earlier, a Butte newspaper rapturously described the local prodigy as having a “clear, rosy complexion…soft, light brown wavy hair (without marcel wave), large and dreamy eyes, pearly teeth and a winning smile.”

A couple of months after their marriage, the newlywed couple spent a day with the Markhams, about which Balk was soon rapturously reminiscing in a letter written to Markham from 321 West 75th Street in New York City:

I shall never forget the day in June my wife and I spent with you at the Y Birch. Had I the power of language to express my great love and reverence for you, I would not hesitate to do so in this letter. But there are some feelings in a man’s heart that can never be spoken or written. Believe me, my dear Edwin Markham, when I say, that I hope (and my wife also) to have many more afternoons with you, and listen to your song, and leaving you feel, as I felt that last time, as one born again.

In his letter Balk detailed his latest reading, specifically mentioning Herbert Paul’s 1902 biography of English poet and critic Matthew Arnold and Swiss moral philosopher Henri-Frederic Amiel’s Journal Intime, which, one imagines not altogether incidentally, had been named by Markham in a 1909 symposium as one of the books that had most influenced him. Balk declared that he was going to read Amiel’s Journal “for the third time,” as well as Thomas a Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ. He closed by praying, “May the Grace of God, and the Love of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the fellowship of the Holy Ghost be with you always.” Markham wrote Balk a five page letter in reply, discussing his own literary views, but this is the last recorded letter exchanged between the two men.

During this time Balk, now labeling himself the Assistant Director of Education for an organization called the English Language Bureau, made a practice of sending letters not only to Edwin Markham but to the New York Times and the Saturday Review, confidently if not always entirely coherently addressing an array of subjects, including divorce, the provenance of great men, the declining quality of American stage plays and Einstein’s theory of relativity, in an apparent effort to flex his intellect before a wider audience. In his letter on great men, entitled “The Hero’s Birthplace,” Balk expressed bemusement for the public fascination with learning all about the humble birthplaces of great men—a telling sentiment from one who had carefully cloaked his own modest origins. (He also made certain to drop the name of his poet friend into the letter: “….as Edwin Markham said to me….”)

Notably ironic are Balk’s letter on stage drama, in which, sounding like a commentator on FOX News, the career criminal–who in my view bore the hallmarks of a classic sociopath–complains that “[n]ow, it seems, psychology, pseudo-philosophy, the hideous, the horrible—and worse—must be the basis of nearly everything put on,” and–given his treatment of his wife (see below)–his letter on divorce, in which he allowed that “[o]ne should honestly be sorry for [married] individuals who are unhappy,” yet urged nevertheless that marriages should be maintained intact, as marriage constituted “the very foundation both of personal morality and social stability.”

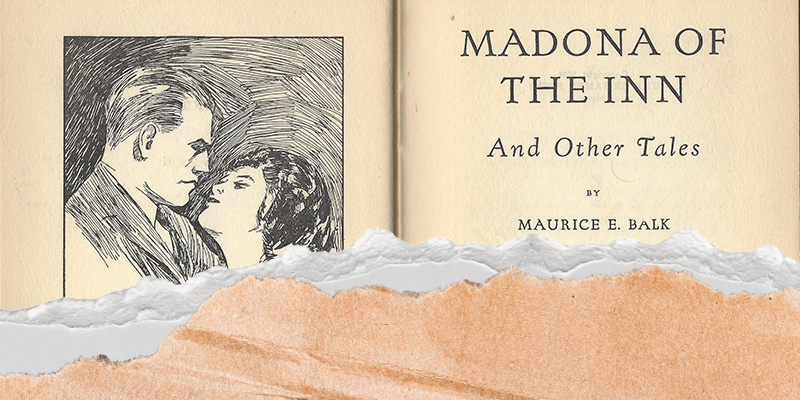

In 1924 Maurice and Teresa Balk moved to Chicago, where Teresa gave birth to the couple’s son, Gerald Langston, on June 6, 1924. That year Maurice also published with Britamer, a Chicago press that suspiciously shared its name with Maurice Balk’s former film production company, what was apparently Britamer’s sole publication: Madonna of the Inn, and Other Tales, a slim collection of six cloyingly lachrymose short stories, including two about loyal pets, one of them whose faithfulness extends into the afterlife, answering the age old question of whether dogs go to Heaven. Another tale is set, unrewardingly, in Nova Scotia, outside Tusket.

Balk dedicated the book “To Teresa Louisa,” including with the dedication a well-known verse from proverbs about the subject of wifely devotion, which begins: “The heart of her husband doth safely trust in her….” Unhappily, Teresa’s heart did not safely trust in Maurice. Nine months after Gerald’s birth, Teresa, deserted by her husband, returned with her son to Meaderville, Montana, where she obtained a divorce from Maurice in 1926. After four years of making her own living in New York, she married bond salesman Louis Martin Fabian, son of a Hungarian immigrant who had risen from miner to businessman and county commissioner.

Maurice Balk had abandoned his wife and son in Chicago in 1925 for fertile felonious fields Caspar, Wyoming, where he talked his way into a position with the Daily Tribune as a book review columnist. At this time Balk was claiming to have been a former employee of the London Times as well as a Great War veteran who served with T. E. Lawrence in General Allenby’s epochal Palestine campaign (although in truth he was sixteen at the time and incurring his first encounter with legal authorities). In August the fabulist contributed to the paper a poem entitled “Mean Desires,” which certainly seems, assuming it is really his own work, to have an autobiographical aspect:

I’ll go, said I, to the woods and hills

In a park of doves I’ll make my fires

And I’ll fare like the badger and the fox, I said

And be done with mean desires.

Never a lift of the hand I’ll give

Again in the world to the bidders and buyers;

I’ll live with the snakes in the hedge, I said

And be done with mean desires.

I’ll leave—and I left—my own true love

O faithful heart that never tires!

I will return, tho I’ll not return

To perish of mean desires.

But the snake, the fox, the badger, said I

Are one in blood, like sons and sires

And as far from home as kingdom come

I follow my mean desires.

Not long afterward Balk left Caspar for Manitou Springs, Colorado (near the larger locality of Colorado Springs), where he started his own newspaper under the posh cognomen “M. E. Sackville Balke.” (Surely the name “Sackville” was inspired by his family’s home address on Sackville Road in Bexhill.) Characteristically his latest business venture seemed to consist of the confidence trickster separating other people from their money in order to line his own pockets. He served a term in the county jail for passing a bad check and was sued for wages by his angry employees, who, according to an article in the Typographical Journal, “had been unpaid in most cases since the paper was started.” Figuratively bloodied but unbowed, Balk in 1927 next turned up at the small Central California city of Lodi, where he held a series of revival meetings and divine healings at the burg’s Tokay Theater. In one of his sermons Balk, who doubtlessly was an expert on domestic disharmony, contrasted “present [day] home life with that which existed at the time of Christ.”

Later that year Balk’s colorful New World adventures were abruptly brought to an end when the conman was ingloriously deported from New York back to Great Britain, US authorities having decided that they had had enough of the incorrigible offender. As a deportee aboard the R. M. S. Berengaria Balk ignominiously set foot in Southampton on September 7, 1927. His occupation was listed as “preacher” and his proposed address in the United Kingdom his mother’s house on Seven Sisters Road. although in fact his mother had died four years earlier.

By the next year Balk had started, in league with a colleague, Arthur Evan Clarke, a small press named “Evanearle,” whose first venture was to be, it was reported in trade journals, “an outline of Jewish history.” Like a moth attracted to a fair, fatal flame, however, Balk seemingly could not keep his mind off the beckoning lands across the pond, with their fields so fertile to fraudulent schemes. Less than a year after his compelled return to England, on March 10, 1928, Balk set out on the Minnesdosa from Greenock, Scotland for Canada, giving as his last address in the United Kingdom his brother Philip’s domicile at 160 (or 166) Oxford Street, Glasgow and his occupation as “publisher.” Balk’s ultimate destination was Toronto, where he had found employment (allegedly) with Robinson & Heath, a firm of customs brokers and freight forwarders. This time his stay was short; less than six months later, on August 3, 1928, he was deported from Canada on board the Melita. His occupation was listed as “medical student” and his proposed address once again his brother’s home on Oxford Street in Glasgow. Back in the UK–and with both the United States and Canada now warded against him—Balk, settled in London, turned first to his father’s field, photography, then went back, after another stint in prison, to publishing. Along with two other “well-dressed” men, Balk, whose occupation was given as “photographer,” in a 1929 court appearance pled guilty to several charges of obtaining, by means of bad checks, goods (including a camera and film projector) from West End salesmen and was sentenced to a year at hard labor. Had Balk had been contemplating taking up film production again?

The next year, on March 27, 1930, Balk was again convicted on charges of larceny and sentenced consecutively to terms of two and six months’ imprisonment. In November of that year the fraudster, who was described as nearly 5’8” with a fresh complexion, brown hair and eyes and a scar on his upper lip, featured in the UK’s Police Gazette under the heading “Expert and Travelling Criminals,” where he was bluntly termed “[a]n unscrupulous fraud.” By this time the Balk’s list of aliases had become formidable indeed, something which American politician and fellow fabulist George Santos might well have envied. Aside from Maurice Earle Balk, he had used, at various points in his criminal career, M. M. Blumenthal (borrowed from his uncle), M. E. Sackville Balke, Reverend E. Balke, William E. Bennett, Reverend Elliott, V. T. Taylor, Albert Caver and Reverend E. E. Langston. Being “well educated,” the Police Gazette warned, Balk found he could convincingly assume “the role of a clergyman,” experiencing “little difficulty…in impressing his victims.” For example, on one occasion, Balk, having called on a clergyman for a friendly theological chat and been briefly left alone by the duped parson in his study, took the opportunity to abstract a blank check from the clergyman’s checkbook, which he later used at a bookseller’s shop to pay for a valuable first edition tome. It should come as no surprise that Balk read (and plagiarized) detective fiction, as in life he behaved like a rogue in an Agatha Christie or Edgar Wallace crime thriller.

Once out of prison again, Balk started a new venture under yet another false name, Philip Earle. In 1931 he established another book publishing press, named Philip Earle after his new identity, at 39 Jermyn Street in London. Although short-lived, “Philip Earle” had rather more substance than Britamer, his 1924 effort, in that the press actually published something more than books written by–or plagiarized by–Balk. Volumes issued by Philip Earle in 1931 include Margaret Hunter Ironside’s Young Diana, Elsa Lingstrom’s Jeddith Keep, two respectfully reviewed contemporary novels, Jane Austen’s epistolary tale Lady Susan (adapted to film in 2016 under the title Love & Friendship) and American journalist Ben Hecht’s controversial novel A Jew in Love—a book proverbially banned in Boston, not to mention Canada, yet which quickly sold 50,000 copies and made the bestseller lists in the US.

And then of course there was Balk’s own effort, in a manner of speaking: the detective novel Cat and Feather, which he published, as we have seen, under the pseudonym Don Basil. The conman had good reason for employing a pseudonym, for, again as we have seen, he had stolen Cat and Feather nearly word for word from Roger Scarlett’s The Back Bay Murders, which the previous year had appeared in the US. The Beacon Hill Murders–the first detective novel by “Roger Scarlett,” the pen name of Dorothy Blair and Evelyn Page–had been published in the UK in 1930 by Heinemann, a major British publisher, but I do not believe The Back Bay Murders had a UK edition. This of course would have made it easier for Balk to carry out his shameless theft of Blair’s and Page’s intellectual property, but the plagiarizer characteristically went a step too far in his roguery when he published Cat and Feather with Henry Holt, a reputable American firm. In the US, Balk’s blatant plagiarism was soon discovered and Henry Holt promptly withdrew the book from distribution. The publishing firm of Philip Earle thereupon succumbed to this latest Balkian brouhaha, while the publisher himself received his comeuppance three years later, albeit for another crime.

In 1934 Phillip Earle was committed, along with a purported aunt, Lucy Griffiths, to trial in London on the charge of conspiring to filch by false pretenses 3389 pounds (a tremendous amount of money, over a quarter of a million pounds, or more than 300,000 dollars today) from an elderly widow, Mrs. Kate Christie Miller of Sutton, Surrey. Before the credulous Mrs. Miller, Balk once again donned his favored guise of a pious clergyman. Dealing her a pack of patent lies, Balk had inveigled the poor woman into repeatedly making him loans which he never paid back. When the case came to trial in January 1934, Mrs. Miller plaintively declared on the stand that the defendant had “told me he had been a preacher of the Gospel in Canada, and he appeared to be a very religious man.” Balk was found guilty and sentenced to four years’ penal servitude.

Sir Ernest Wild, the senior presiding judge at the Old Bailey, who was known to have “sent many murderers to the gallows and tried to extend the use of the ‘cat’” and in 1920-21 was involved with efforts to criminalize lesbian sex, sternly lectured the prisoner: “Anything more hypocritical and wicked than your frauds is impossible to imagine. What makes this series of crimes particularly mean is the way in which you invoked the Deity in your letters [to Mrs. Miller].” Invoking a more worldly literary authority, William Shakespeare, Justice Wild with a theatrical flourish quoted from the play The Merchant of Venice to remind Balk:

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.

An evil soul producing holy witness

Is like a villain with a smiling cheek.

A goodly apple rotten at the core.

O, what a goodly outside falsehood hath.

Undeterred and presumably unashamed by this vivid judicial admonition, Balk adopted, after his early release from jail in 1937, yet another, more exotic authorial guise, Maure Balque, under which he wrote, but naturally, an inspirational book of religious verse, The Christ I Know, as well as a pamphlet on the 1937 coronation of King George VI, which were published, most conveniently, by the firm of “M. E. Balk.” By 1939, however, the incorrigible criminal was back in prison again, at His Majesty’s Prison in the midland city of Leicester, sadly still unredeemed.

At the outset of the Second World War, after he had again become a free man, Balk, now living in the posh London district of Hampstead and claiming to be a radiologist, wed a Jewish Austro-German refugee named Frieda Birnbaum. Born a decade after Balk in Vienna, Frieda, having been exempted by the British government from its wartime internment of German and Italian nationals, worked as a domestic servant, though she had been formerly employed as a secretary. How many years did it take for Frieda to wake up and smell the coffee? In 1944 her felonious husband was arrested on charges of fraudulently obtaining a line of one thousand pounds credit with the business firm of General Radiological, Ltd.–Balk was an undischarged bankrupt–and absconding with a “set of Dickens books worth L44.” At least the unmitigated rotter’s tastes remained literary!

In 1947 Balk, who had become a paid contributor to the American Methodist weekly magazine the Christian Advocate, was in court yet again, this time back in Leicester, on further charges of credit fraud as well as a charge of having committed bigamy against his now estranged wife Frieda after he in Kensington that year wed a certain lady named Gladys Rankin. Detective-Sergeant Woodward of the Yard testified that Balk, who claimed to have studied at Harvard University, had numerous previous convictions. Clearly Balk was on a downward spiral in the battle of life. Where his youthful crimes, while unquestionably wicked, had a certain scale and panache to them, his later interactions with the law seem merely squalid and pathetic.

When Balk applied for a discharge of his debts in 1949 bankruptcy proceedings, he was residing at 16 Colville Mansions in Bayswater, in a neighborhood that had become “largely a slum area,” with “large houses turned into one-room tenements and small flats.” A vivid contemporary portrait of Colville Mansions is provided by the Liberal Democrat MP Shirley Williams, who in her memoirs has recalled for two-and-a-half years during the early 1950s sharing with two friends a “rickety flat” located on the top floor of a Victorian terrace called Colville Mansions, just off the Portobello Road. We had found it after a discouraging search through West London, in which we were offered flats without baths, flats with cockroaches in possession, and even flats with mirrors in the ceiling, a reminder that Bayswater had long been a favourite venue of the world’s oldest profession. Colville Mansions was at least reasonably light and airy, but the trouble was the roof. It leaked so badly we had to sleep with buckets around our beds, and eventually with a tarpaulin draped over the worst holes. This, however, was but a foretaste of what was to come. One evening, with a mild roar, the entire front cornice of the building collapsed into the street below.

However poorly the many people victimized by Maurice Balk over the years may have thought of him after the wool had been pulled from their poor deluded eyes and the cornice had come crashing down before them, there is no question that Maurice Balk was a survivor. He lived to see his eighth decade, passing away obscurely in 1981. Currently I know nothing about Maurice Balk’s later years, aside from the facts that he had the effrontery in 1958 to renew his copyright on Cat and Feather, that for a time in the Sixties he supposedly edited something called the Journal of Auxiliary Medicine and that he is said during that same decade to have composed a Memorandum on Prison Reform—this last, at least, a subject to which Balk doubtlessly brought considerable legitimately earned authority.

Postscript: The Apple Falls Far from the Tree

Readers may wonder whatever became of Maurice Balk’s son, Gerald Langston Fabian, last glimpsed as a fatherless waif in Meaderville, Montana. After their 1930 marriage in New York, his lovely and talented mother Teresa and his successful and dutiful stepfather Louis Fabian moved with young Gerald to Beverley Hills, California, where Louis worked an investment banker and later served as president of the Beverly Hills Chamber of Commerce. A graduate of the US Naval Academy and an officer in the Naval Reserve, Louis during the Second World War was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander in the Pacific theater. In this capacity he received the Navy Cross, in recognition of “extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as the Senior Squadron Beachmaster, during action against enemy Japanese forces at Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands, on 20 November 1943.”

At the beginning of 1943, eighteen-year-old Gerald Fabian, who had graduated the previous year from University High School, Los Angeles, was a freshman at UC Berkeley, where he was an assistant editor on the annual staff. (In high school he had been an assistant editor of the student newspaper.) On February 25 in San Francisco he enlisted in the US Navy. According to his obituary in the Bay Area Reporter, Gerald served in the Pacific, including “once under his stepfather who commanded [his stepson’s] ship at Iwo Jima.” After the war Gerald returned to attend classes at UC Berkeley, where he majored in Romance Languages, but he was, according to a friend, the San Francisco writer Lew Ellingham, “expelled…because he was gay.”

Despite this setback, Gerald, who according to his obituary was a “person of culture, erudition, and talent” who had become acquainted while at Berkeley with Jack Spicer and other members of the San Francisco Renaissance, over the next half-century taught language classes at the University of San Francisco and elsewhere, worked as an actor in San Francisco stage productions, published poetry and was active in gay community groups in the City by the Bay. In 2003, nine years before his death in 2012 at the age of 88, Gerald gave an interview to the Monferrini in America website about his Italian heritage, concerning which he was tremendously well-informed and justly proud. “I think it’s important to find out as much as possible about one’s background and history,” he commended at the time. Whether Gerald knew anything about his remarkable criminal birth father, however, is currently unknown to me. Gerald Fabian appears to have had some of the mental capacities of the undeniably able Maurice E. Balk, yet happily the younger man developed these capacities in pursuit of altogether more admirable aims.

Note: All five of the Roger Scarlett detective novels, including the plagiarized The Back Bay Murders, were reprinted by Coachwhip in 2017. One of the Scarlett titles, Cat’s Paw, was selected for Otto Penzler’s American Mystery Classics series in 2022. Don Basil’s Cat and Feather remains out of print, however, Maurice E. Balk’s incredible criminal career having been long forgotten until I first publicized his perfidy in 2018. That same year the book was mentioned in the LitHub article “25 of the Most Expensive Books You Can Buy on the Internet,” which noted that a copy of Cat and Feather, “plagiarized from The Back Bay Murders by Roger Scarlett,” was being offered for the tidy sum of $250, 275 by veteran bookseller Rushton H. Potts. Somewhere Maurice E. Balk must have been smiling.