Why do people crave crime fiction? Some theorize that we seek justice and order, and when we don’t find it in our lives, we can always find it in the pages. The detective or sheriff or reluctant investigator will always get her man. Truth will prevail. That’s one theory.

Here’s another. The crime is a clearly defined inciting event (writer speak for that moment when you know what the book is about) and as such, the protagonist’s want is well established. As our protagonist sets off on her quest to fulfill this want, we are desperate to find out if she succeeds. We find fulfillment vicariously, as we root for the protagonist to finish her quest. We’re also drawn to the genre because its stakes are most often life and death. And it’s these highest of high stakes that fuel my interest in a novel—be it crime fiction or any other type of fiction. It’s that thing, that elusive thing, that sticks to my ribs and holds my interest for the hours I spend reading a novel—or the two to three years I spend writing one.

This is a part of the writing process I think little about, as if in thinking about it, I’ll scare it off. It’s bigger than the laws that are broken by the criminals in my novels. Bigger than the religions my characters might practice or the politics they might hold. Bigger, really, than the life or death struggle that crime fiction delivers. It is moral struggle in and of itself that motivates my work. I found it in the last lawful public hanging that took place in the United States in Owensboro, Kentucky. I found it in a boys’ reform school that allowed the abuse of children for over 100 years. And most recently, I found it in comments made by the president of the United States in the wake of the Charlottesville tragedy that took place in August 2017.

I’ve written here on CrimeReads before about one of the first rules of writing I learned and one I continue to follow today: write the book you want to read. I want to read books that deliver smartly drawn plots, but that also mine the greater moral issues that make us all part of the story. Below, I’ve summarized a few crime novels I believe do just that.

Unnatural Death (1927) by Dorothy Sayers

Dorothy Sayers was unique in her time in many ways. As a child, she was educated by her father and with boys, both unusual during the early 1900s. Additionally, she went on to study at Oxford during a time when women had to be chaperoned by men and was one of the first women to earn a Master of Arts from the institution. Just as she broke with norms in her real life, she similarly broke with them in her fiction. In Unnatural Death, Sayers protagonist, Lord Peter Wimsey, becomes suspicious when an elderly, wealthy woman, having been given only a few months to live, dies much earlier than expected. In the course of this novel, Sayers introduces Alexandra Katherine Climpson to work alongside Lord Wimsey. Miss Climpson proves herself to be a natural investigator and ultimately oversees a detective agency that is staffed fully by women and masquerades as a typing bureau. In addition to challenging these cultural norms of the time, Sayers challenges the moral norms of the time by also introducing several characters in the novel who, though Sayers never specifically articulates it, we are to conclude are gay.

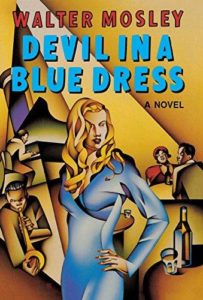

Devil in a Blue Dress (1990) by Walter Mosley

The author of more than 40 books, fiction and non-fiction, Walter Mosley began his writing career following a job as a computer programmer. In his debut novel, Devil in a Blue Dress, which was nominated for an Edgar Award for Best First Novel, Mosley introduces his protagonist, Easy Rawlins. After serving in WWII, Rawlins returns to Los Angeles where he takes a job in a factory, buys a house and settles into a routine. But his plan for a simple life is interrupted when, while working at the factory, a place Rawlins describes as a plantation, he stands up to his white supervisor and is fired for having done so. In order to pay the bills and retain his independence, Rawlings reluctantly accept a job investigating a woman who has gone missing in Watts. Writing against the backdrop of Watts in the post WWII era, Mosley, as he has done through the 14 books in the series and his many other works, tackles racial discrimination, violence in America and an unjust justice system.

The Long Goodbye (1953) by Raymond Chandler

When my second novel was close to coming out, a friend emailed me a link to an article about a research study. In the study, three people, via a computer game, threw a digital ball back and forth. At a certain point, one person was excluded for no apparent reason. Upon studying the physical response of the excluded person, researches found that the need to belong is so strong in human beings that when excluded, they experience a physical pain such that it can be treated with Tylenol. Raymond Chandler, who became a writer after losing his job during the Great Depression, is widely credited with being the founder of the hardboiled crime novel. But I include him here today for his examination of this desperate need to belong, a need most certainly tied to our very survival. Specifically, the need for acceptance and the crushing loneliness when we are denied it is at the heart of The Long Goodbye, the sixth of his seven novels.

The Black Echo (1992) by Michael Connelly

Michael Connelly is the author of thirty-three novels, most of which feature Harry Bosch. Connelly published his first novel, The Black Echo, which won the Edgar Allen Poe Award for Best First Novel, in 1992. And in all the Bosch books that have come after, Harry Bosch’s personal motto has driven the narrative. Everybody counts or nobody counts. In those few words, Bosch’s moral code, greater even than his professional code of ethics, drives his choices and actions, both of which give insight into the greater failings of society, such as inequities in the justice system and the ongoing class wars. Because I have a fondness for reading an author’s first work, I’m highlighting The Black Echo here. In our first meeting with Harry Bosch, he is investigating a crime scene where a dead body is being pulled from a drainpipe. Though others in the investigation want to declare the death an overdose in order to dispose of the case quickly, Harry presses on, and when the body is ultimately pulled from the pipe, he recognizes the man as someone he served with in Vietnam.

Them by Joyce Carol Oates

When, several years ago, I was in the early stages of writing a book set in Detroit, I read Them by Joyce Carol Oates. Because it has been so long since I read the book, I couldn’t recall the specifics of the plot without refreshing my memory with a few summaries, but I do clearly remember that upon finishing the book, I began to observe people more closely. As I went about my daily life, I took note of the details I noticed about someone. I found myself dissecting what I assumed, based on my observations, about these strangers and why. I found myself wondering what they assumed about me. Them did for me what great fiction can do for all of us. More than any other form of storytelling, a great novel lets us walk in the shoes of another person and allows us to see the world through his or her eyes. It builds understanding and empathy. In the case of Them, we see the world through the eyes of a family living in the slums of Detroit during the years leading up the riots of the late sixties. Oates is one of our most prolific writer, crime or otherwise, and Them is only one example of her work that tackles moral issues beyond the crimes that drive the plot.