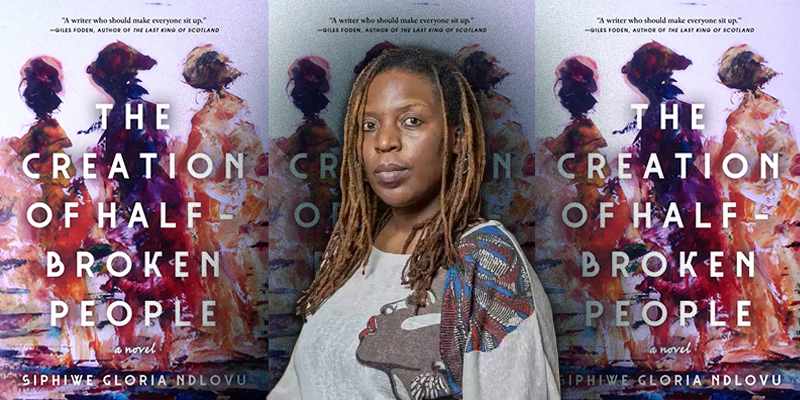

At the highly impressionable age of eleven, I moved with my mother from the smallholding that had shaped my young life and nascent imagination to a wonderful bungalow in the suburbs of Bulawayo. All the houses looked the same—modest single-story abodes tucked away on acres of land and bordered by bougainvillea or hibiscus hedges. All houses that is, save one. The house that broke the uniformity was not a house at all but a castle—a seemingly abandoned, crumbling ruin hidden behind a fortress of never-green savannah vegetation—situated two houses down from where I lived. The entire place was shrouded in mystery for me. Who had built it and why? And, perhaps, more importantly, why had they abandoned it and left it to decay? While I had much curiosity and strong powers of invention, I must not have possessed even a modicum of courage for I never ventured onto the property to steal my way into its cavernous interior, scurry along its secret passages, creep up its decrepit stairwells, encounter its undoubtedly many ghosts and find myself trapped in one of its ancient chambers. However, it was a place that undoubtedly haunted me throughout my life’s journey for it will probably not surprise you to learn, Dear Reader, that after such an auspicious beginning, I have written an African Gothic novel, The Creation of Half-Broken People.

At least, I think that is what I have done. If you type ‘African Gothic’ into your favorite browser chances are that the search will not yield many results that seem pertinent to what you are looking for. You will be encouraged by certain results only to be disappointed when you realize that they point to canonical texts of African Literature onto which literary critics have read ‘elements’ of the Gothic.

Surely African writers have intentionally written works that they themselves would define as Gothic. However, after spending some time searching for ‘African Gothic’ literature on your favorite browser you may very well start to feel that you are navigating your way through a series of dark and winding tunnels, candelabra in hand, dread growing stronger with every step as you begin to suspect that there is no door to enlightenment at the end of the tunnel. And then, as often happens when you are deep in the catacombs, a sudden gust of wind extinguishes the candles.

Before you can fully comprehend the horror, there is a glimmer in the distance. You rush towards it and, breathless, discover ‘Afro Gothic’ art and literature—a genre that uses Gothic tropes, motifs, and aesthetics to speak the violence of colonial slavery in the Americas and the Caribbean, the terror of its quotidian ubiquity, and the traumas it visited upon the black body. These traumas are stored, metabolized, remembered, passed down, and inherited generation after generation, creating a genealogy in African Diaspora literature that can be traced from the slave narratives of Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglas to the works of Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler. Surely, there must be a similar genealogy that speaks of the violence and traumas of slavery and colonialism on the African continent.

Suddenly there is another glimmer in the distance. You rush towards it and, breathless, discover ‘South African Gothic’ art and literature—a genre that uses Gothic tropes, motifs and aesthetics to speak the anxieties over history, place, space, culture and power that colonial Europeans travelled with and transplanted onto new landscapes where the natives were always imagined as the barbarians at the gate and the white body imagined as the one under constant threat of violence. Just as the perception of the German Goths as uncivilized, uncultured, and unenlightened people created a fear and a fascination with the medieval architecture that bore their name and that allowed Horace Walpole and other eighteenth-century writers to explore the darker recesses of the human heart, so, too, did the perception of the colonized native people as uncivilized, uncultured, and unenlightened create a fear and fascination in settler colonial writers that allowed them to explore the darker recesses of the human heart. The horror! The horror!

A core fiction of the colonizing mission was that it was a civilizing mission and, therefore, the horror of the heart of darkness could not reside comfortably within the white body because to have it do so would be to acknowledge the violence of the civilizing mission. As a result, there was much ambivalence and ambiguity—an unsettledness, if you will—in the creative production of settlers.

This could explain why, given this inheritance, there is a reluctance to use this initially Eurocentric genre and its othering gaze to define some aspects of the postcolonial and post-apartheid writing coming out of Africa.

Another reason why your favorite browser may not yield many results when you type in ‘African Gothic’ is because, as Shubnum Khani reminds us, hauntings, ghosts, damsels in distress, malevolent spirits, things that go bump in the night, supernatural goings on, stories that fill us with terror, are not just the purview of the European storytelling tradition, all storytelling traditions contain these elements so who is to say that an African novel that has some of these tropes and motifs is borrowing from the Gothic tradition and not from a more local/non-European tradition.

Does it matter? Should it matter? When I wrote The Creation of Half-Broken People I definitely wanted the Gothic to matter. My first introduction to the genre was when I read Jane Eyre in high school in my A-Level English class. Having been primed by most of the literature that I had consumed till that point to sympathize with the often-white protagonist of the story, my encounter with Bertha Mason turned out to be a revelation. My superb teacher, Mrs. Joan Madonko, made me realize that Bertha Mason in all her wretchedness was not something to fear as Jane did and Mr. Rochester encouraged, but was instead someone that I, a black girl living in a former British colony, should understand and feel an affinity towards. It then occurred to me that literature, the very thing that I had always used to expand my imagination, had trapped me in some way because my non-white, female body was something so inconvenient and feared that it had to be lied about, locked away, rendered dangerous, and defined as mad. I needed to find a way out. I needed to escape. The only way out I could find was through writing.

When I made my first real attempt to write a novel, the first character who came to me was Elizabeth Chalmers, a mixed-race woman who sees visions that tell her she needs to fulfill an ancient prophecy.

While she is on her quest she encounters the colonial system which immediately reads her as schizophrenic and places her in an asylum. The story had many false starts… until I decided to deliberately write it as a Gothic novel—as a story that is in conversation with Jane Eyre. Just as Horace Walpole and his eighteenth-century contemporaries had looked to the Middle Ages and the ruins that that era had left behind to illuminate the anxieties and tensions of their seemingly more enlightened historical moment, so too could I, as a postcolonial writer, look to the colonial era and the ruins it has left behind to illuminate the anxieties and tensions of my seemingly more enlightened historical moment. Finding the setting for my story was easy, I had, after all, grown up two houses down from a castle.

i Decolonizing the Gothic.

***