I wish I was the kind of person who could live happily in all kinds of places. Don’t get me wrong; I love to travel, and I’ve lived in most regions of the country at one time or another, from Washington, DC to the Central Coast of California, to Missouri and northern Michigan. There were things I liked about each of the cities and small towns I briefly called home, but I couldn’t see myself settling permanently in any of them, and after a while I figured out why: I’m a Southerner.

This is partly background, partly temperament. My father’s family settled in Virginia in the mid-nineteenth century, and I feel in a way that’s hard to put into words that the Blue Ridge Mountains are in my DNA, woven into the essential fabric of my being. I don’t think there’s anything more beautiful in the world than the line of those mountains on the horizon. As far as my Southern bona fides go, I also make my own jam and a pretty decent chess pie, wear pearls, know where to get moonshine, say y’all, and listen to country music (not always ironically). I like it here, and I’m planning on staying for the duration.

Still, a Southerner is not always a comfortable thing to be. Politically, my home state seems to be in a permanent pattern of two steps forward, one step back. In the small-town South, the pressure to conform can be stultifying, and as the mother of a special needs child and the stepmother of a non-gender-conforming child, I worry that a place where I feel accepted may feel exclusionary and oppressive to others.

I wanted to unpack some of these tensions in my debut thriller, The Good Ones, where the main character Nicola moves back to her small Virginia hometown after the death of her mother. Sixteen years earlier, Nicola’s friend Lauren Ballard disappeared suddenly, leaving her husband and young daughter behind. At first Nicola resists the idea of settling back into old patterns and renewing old friendships, not just because of the trauma of Lauren’s disappearance, but also because her identity as a queer woman makes her feel like a permanent outsider in her own home.

What I love most about Southern crime fiction is the way it explores what it means to love a place that may not always love you back. Here are seven great novels that celebrate the beauty and the magic of this region, while also acknowledging it’s not always an easy place to call home.

Ace Atkins, The Ranger

When I find a series I like, I binge it like it’s the new season of a reality show, and that’s exactly what I did with Atkins’s Quinn Colson novels. In this first novel, Colson returns to Tibbehah County, Mississippi after leaving the Army and gets sucked into the atmosphere of lawlessness and disorder that he thought he’d left behind. In later novels, he settles into his role as county sheriff, but I especially love his uncertainty in this first book, when he’s discovering how bad things really are but hasn’t yet figured out what to do about it. I’ve learned so much from Atkins about writing action scenes, and his writing is full of evocative detail that brings the landscape of north Mississippi alive on the page. He also writes great women: Quinn’s friend and righthand woman Lillie Virgil and his sister Caddy are complicated and fully realized characters who develop from book to book.

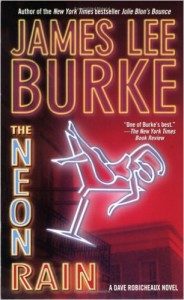

James Lee Burke, The Neon Rain

I’ve read every one of the Dave Robicheaux novels, but in my opinion they don’t get any better than the first in the series, The Neon Rain. Just listen to this opening: “The evening sky was streaked with purple, the color of torn plums, and a light rain had started to fall when I came to the end of the blacktop road that cut through twenty miles of thick, almost impenetrable scrub oak and pine and stopped at the front gate of Angola penitentiary.” Burke’s writing is masterful, and the action doesn’t let up from the moment that Dave is given a mysterious warning by the convict he’s gone to visit until the (surprisingly upbeat) ending. Though this novel is set in New Orleans, the rest of the series takes place mostly in Cajun country, where Burke chronicles the environmental devastation of the Louisiana Gulf Coast as the backdrop to Dave’s crime-solving. The twenty-fourth in the series, Clete Purcel, is due out next year, and I can’t wait.

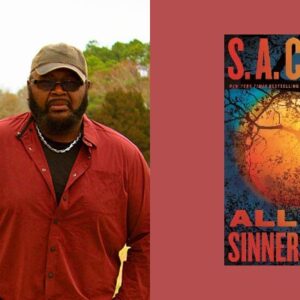

S.A. Cosby, Blacktop Wasteland

I’m not sure this is my favorite of Cosby’s novels (seriously, how do you choose?), but it’s the one that first made me fall in love with his work, in the killer opening scene where Beauregard (Bug) Montage smokes the competition at an illegal drag race, gets shaken down by dirty cops, finds he’s been double-crossed, and then wreaks his own revenge. As a child I spent a lot of time in the part of southern Virginia, known as Southside, where this novel is set, and Cosby writes in such a way that I could smell the honeysuckle and red dirt coming off the page. I’ll never drive through Newport News again without thinking about the scene where Bug jumps an overpass on Interstate 64 and then calmly drives away. Pure magic.

Amy Greene, Long Man

I don’t think anybody writes Appalachia better than Amy Greene. When I was thinking about this list, it was a toss-up for me whether to include Long Man or her debut, Bloodroot, but I had to go with Long Man because the story at its center—the disappearance of a three-year-old girl from a town about to be flooded by a government-built dam—is so compelling and so terrifying. I’ve always been fascinated by the real-life stories of the towns flooded by the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930’s, and Greene makes powerful use of that history of betrayal and longing. This is one of those novels that I remember with such clarity that I feel like I lived through them, and I can’t wait for Greene’s next book.

Attica Locke, Bluebird, Bluebird

I don’t know Locke’s East Texas the way I know the settings of some of the other novels on this list, but her writing is so vivid and immersive that I feel like I’ve been there. Bluebird, Bluebird is the story of Darren Matthews, a Black Texas Ranger investigating two murders in the small town of Lark. Locke captures the ambivalence of feeling tied to a place known mostly in the outside world for a tragic history of violence, as in this scene when Darren remembers his law school classmates talking about the lynching of James Byrd: “he felt a hot rage at the students and professors around him, most of them white northerners, clucking their tongues and whispering Texas in a way that suggested both pity and disdain for a land that Darren loved, a state that had made him a gentleman and a fighter in equal measure.” Locke asks crucial questions about who gets to claim a Southern identity, and what that identity might mean in a more equitable future.

James McLaughlin, Bearskin

I’ve been told that McLaughlin spends part of the year living a few towns over from me, and I’ve had to resist the urge to show up on his doorstep just to tell him how much I love this book. Rice Moore is working as a caretaker on protected land in the Virginia wilderness, but he’s also hiding out from the Mexican cartels that want to kill him. McLaughlin has a way of using the details of country life to create an atmosphere of incipient violence, as in an early scene when Rice is attacked by bees while trying to fix up his cabin. Later, after finding that someone has been hunting bears illegally in the preserve, he makes his own ghillie suit as he lies in wait for the culprit. This novel is a page-turner for sure, but high stakes and high tension aren’t all it has to offer—it’s also a deeply-felt evocation of the strange and eerie beauty of the Southern Appalachians.

Donna Tartt, The Little Friend

If I thought I could get away with it, I’d probably include The Secret History on this list, though I know a novel set in Vermont with a main character from California would be an odd fit for a roundup of Southern crime novels. Still, anyone who has listened to the audiobook, narrated by Tartt herself, would have to admit that the novel has an unmistakable Southern vibe.

The Little Friend is the only of Tartt’s novels to be set in her native Mississippi, and it’s rich with the nightmare details of Southern gothic, in which the beautiful seamlessly metamorphoses into the uncanny. I first read it when it came out in 2002 and found some aspects of the plot frustrating, but I’ve returned to it in recent years, and I’ve come to think that the frustration might be part of the point. What we read for in crime fiction, after all, isn’t always the resolution of a mystery; it’s also to understand what it’s like to construct a life in the aftermath of trauma and tragedy. In a region where the past is never past, these novels teach us something about what it’s like to pick up the pieces and keep going.

***