Long before the doors opened, a crowd gathered outside the theater. Noisily, they bustled in, country folk and urban dandies alike, to find themselves good seats. The old mansion’s walls reverberated with their footsteps on the hardwood floors, spirited greetings, idle gossip, and talk of politics.

The playhouse had once been the country home of Aaron Burr, who nearly thirty years earlier returned across the Hudson River to his Richmond Hill estate from the New Jersey palisades after his notorious duel with Alexander Hamilton. As Burr’s fortunes waned and the growing city encroached from the south and east, John Jacob Astor purchased the mansion, lifted it and rolled it a few blocks closer to the center of Manhattan, and converted it into the Richmond Hill Theatre.

Earlier the same summer a teen-aged Walt Whitman had described feeling mesmerized by the dark green curtain of a New York theater. Transfixed when it lifted, with “quick and graceful leaps, like the hopping of a rabbit,” Whitman knew that behind the drapery lay a “world of heroes and heroines, and loves, and murders, and plots, and hopes.” As the Richmond Hill’s curtain rose this September night, a cotton factory at sunrise came into view. Young women conversed as they commenced their work, beginning the night’s feature, Sarah Maria Cornell: or, The Fall River Murder.

Surely the audience erupted as Matilda Flynn entered as the title character. Playing opposite drama’s biggest male stars the previous autumn in New York, the twenty- something actress found herself now headlining a company full of amateurs and unknowns.

As Sarah Maria Cornell, she breaks into the factory-floor gossip of her co- workers:

“Good morning sisters. I have been a lazy girl; you have got ahead of me.”

“What detained you Sarah? You are not usually behind us at work.”

“I have had such a dreadful dream . . .”

As Cornell relays her premonition that she will die a violent death at the hands of another, the girls gather around, occasionally interrupting her to remind the audience that, no matter her fate, Cornell is a “good, virtuous, and industrious” woman.

And so an onstage whirlwind began, carrying the audience from a cotton mill with its “factory girls” to a farmhouse of guileless Yankees—familiar stock characters— to an isolated, wooded glade where a camp meeting and a Methodist minister evoked chaos, sex, violence, ambition, and greed, before drawing to a close at a haystack with the killing foretold in the play’s title.

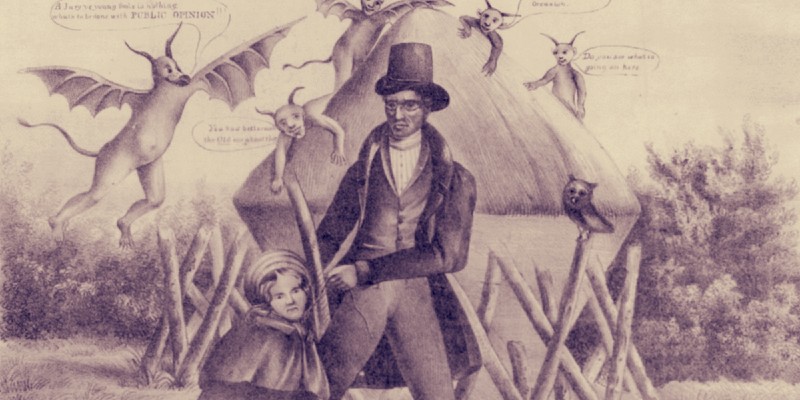

None of this surprised the Richmond Hill audience. Entering the theater, they passed enormous posters depicting in graphic detail the scene of a man strangling a woman. They had seen similar images in handbills plastered on street corners, with smaller versions adorning their playbills.

They knew the characters and the story before the curtain rose because it mirrored a real- life drama that played out in newspapers for months in 1833. By summer’s end, the factory girl and the preacher had become cultural celebrities, immortalized in at least two plays and in songs about the affair that were performed in Broadway revues for months on end.

Young America had little experience yet with a phenomenon that would one day be a defining feature of popular culture in the United States: sensational criminal cases that garnered the label “crime of the century”— no matter how frequently such crimes occurred. Here was the nation’s first spectacular trial, and Americans couldn’t get enough of it. Theatergoers had come that evening— and would return night after night— to experience a scandal performed in accelerated time.

When theatergoers purchased a ticket in the 1830s, they expected a smorgasbord of entertainment— Shakespeare plays, farces, a medley of popular songs, circus stunts, equestrian troupes— sometimes all on the same night. Or they might be hoping for a melodrama, a play depicting a morally polarized universe of good and evil, of innocent virtue and depraved villainy. Audiences sought out melodramas because, as Herman Melville observed, they wanted performances that offered “more reality than real life itself can show.” Yet in Cornell’s story, real life itself resounded with the unmistakable qualities of melodrama. Passion, virtue, seduction, a vulnerable young woman, a hypocritical villain, dark plotting, and irrepressible urges to speak incessantly in order to leave nothing unsaid, all were on full view in this scandalous murder case.

Still, Sarah Maria Cornell at the Richmond Hill was not a typical melodrama. It borrowed from comedies and Gothic horror, and most important, its virtuous heroine neither triumphed over nor escaped from her villainous, seducing foe. Instead, this protagonist met her demise through rape and murder.

The real-life demise of Sarah Maria Cornell and all that followed illuminate the very essence of a transformative moment in history, unveiling what anthropologists call a social drama. Such a drama begins when normal and peaceful means of redressing a crime fail to satisfy longings for more complete explanations. Social dramas prompt two questions: Why did this happen? and What does it tell us about who we are? An ensuing scandal reveals deep cleavages emanating from the struggle to come to grips with a world seeming to change before one’s very eyes. Public fascination with the crime exceeds the bounds of normal curiosity surrounding everyday gossip and news. In search for answers people look to cherished beliefs about politics, religion, and family. They turn to familiar stories and plots to make sense of human actions and their repercussions. Collectively, they participate in an enveloping drama that, in turn, transforms the world they sought to comprehend.

Audiences flocked to the theater or purchased popular reading about the factory girl and the preacher so they could take part in a scandal rich in personal meaning. In the stories of the saga’s key characters they saw the experiences of their neighbors and families, sensing keenly that issues that mattered in their own changing lives were being played out in a legal thriller. They understood that women in a new workplace called the factory had uncharted opportunities to live independent lives, but they could also be exposed to sexual threats and to rumors and gossip, threatening their livelihoods and reputations. They knew too the disparity of power brandished in sexual violence and its double standard of culpability. Long before organized movements to confront sexual harassment and sexual violence, Americans understood and explained these real dramas with their own ideas about vulnerability and coercion.

Those who were captivated by this story sensed too what was at stake when evangelical religion began to take center stage in their culture and politics. At a dizzying pace, religious beliefs and personal identities were becoming intertwined with the economic marketplace and partisan politics of a young democracy. Even if they couldn’t foresee the long history of a politics that construed personal choices and a changing society as contests over moral values, Americans knew the cultural battles exposed by such a scandalous case. They sensed especially that fast- changing new forms of communication— an explosion of new print media— mirrored the incessant movement of individuals into new communities and new professions.

If this shocking tale of a preacher and a factory girl constitutes a social drama, it is a drama with a multitude of narrators, scripts, and performers— a contest over stories and storytelling. Stories reveal what mattered most to people in the past; how they lived their lives; how they explained their own actions and the behavior of friends, neighbors, and strangers; and how they communicated their most deeply prized values. Stories expose as well how little people understood the historical transformations that shaped their personal lives, their society, and their culture.

Murder in a Mill Town is a tale in which violence and storytelling expose the personal histories of two complicated people whose lives intersected amid an ever- changing world that each of them tried to embrace but could not control. Although they lived in an exceptional time, they were not themselves exceptional human beings. Their personal histories survive as narratives of ordinary people whose experiences embodied the spirit of a new world taking shape right before their own— and our— eyes.

___________________________________