“There is nothing more dangerous than security” – Sir Francis Walsingham, spymaster to Queen Elizabeth I of England

In 1988, I read The Last Ship by William Brinkley which centers on a crew of one-hundred-and-fifty-two men and twenty-six women assigned to the U.S.S. Nathan James when nuclear Armageddon breaks loose and the ship’s captain has to find a refuge from the poisonous radiation that is rendering his men sterile and his women without any healthy sperm to start repopulating the earth. It’s a long book, more than six-hundred pages, but I’ve read it at least three more times in the intervening years. As I recall, the book offers no explanation for how or why this final war started, but that never bothered me. If the missiles ever start flying, the point is likely to be moot anyway.

My fascination with non-zombie, atomic-apocalypse “what-if” tales began for one simple reason. In 1938, in a laboratory in Berlin, three chemists changed the world forever. Before then, man, as cruel and destructive as he had proven to be in the millennia leading up to it, had never possessed the potential to end all life as we know it. But splitting the uranium atom was a Pandora’s Box—literally lighting the fuse that could blow up the world. The Manhattan Project quickly followed, as American concern over Germany’s nuclear ambitions became paramount. Those secret activities, like all military operations throughout history, proved hard to protect. Hence, Sir Francis’s remark about the danger of security.

Almost as fast as the development of the bomb itself came the first fictional accounts of how it might be the end of everything. Nevil Shute’s pioneering On the Beach was published in 1957 at the height of the Cold War when the U.S. and Soviet governments had recently graduated to the hydrogen bomb and were testing them in the open air. It is the first important novel to deal with the horror of what would happen to those of us unfortunate enough to survive the initial blasts.

Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon followed in 1959. It was the same year that Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist and one of the principal scientists on the real-life Manhattan Project, was released from prison after serving his sentence for revealing the West’s nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. He departed for East Germany shortly thereafter where he died almost thirty years later, perhaps somewhat less confident that his decision to spy for the other side had somehow made the world a safer place.

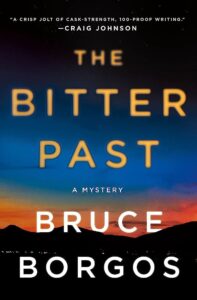

Fuchs, David Greenglass, Theodore Hall, Morris Cohen—the list goes on, all highly educated people embedded in America’s nuclear program who believed they were serving a higher purpose in serving two masters. Were they? It’s a question I take on in my new mystery The Bitter Past, a dual-timeline story in which the current sheriff of Lincoln County, Nevada, is trying to solve the grisly murder of a retired FBI agent. His jurisdiction is just downwind of where hundreds of those warheads were detonated in the 1950s and where that radiation eventually settled to the ground, poisoning everything and everyone it touched. The novel moves between the present and the past and considers two very important “what-if” scenarios: (1) what if the Soviets had sympathizers not only working in the New Mexico lab at Los Alamos but had also managed to place an intelligence asset in the Nevada Test Site, and (2) what if that spy managed to get his hands on a working bomb?

When I began outlining this book in 2019, I was already steeped in the fiction of nuclear nightmare. Not only the novels but the movies too. I was transfixed watching War Games (1983) in which a young Matthew Broderick matches wits with an AI nuclear defense computer program which has run amok (boy, isn’t that timely?) and is ready to start a full-scale nuclear exchange. Crimson Tide (1995) was another creative look at what might happen if the two senior officers aboard a nuclear submarine disagreed over their respective interpretations of launch protocols during a period of hair-trigger political tension in the world. The Day After and Testament, both released in 1983, scared me more than The Exorcist ever did.

I keep going back to what Walsingham knew five hundred years before the rest of us: there is nothing more dangerous than our efforts to make ourselves safe. We invented the bomb to make sure the Nazis didn’t get it first and used it to end World War II and eliminate the need to invade Japan, an effort that would have cost countless more Allied soldiers and sailors. Best estimates—and there is no scientific consensus on this—suggest that more than 100,000 Japanese people died as a direct result (including decades later) of those detonations. We then rationalized our development of even more powerful bombs with the belief that we needed to stay ahead of the Russians and achieve a strong nuclear deterrent. We could argue from now until we blow each other up over whether that strategy has been sound. It works until it doesn’t. It’s as simple and as deadly as that.

I grew up in the harsh sunlight of the Nevada desert not long after and not far from where the Soviet spy in The Bitter Past goes to work. In the 1950s, the prospect of nuclear Armageddon had school children hiding under their desks in Duck and Cover drills and their parents digging fallout shelters. We tested those warheads above the parched, cracked ground of sand and tumbleweeds, lighting up the sky for hundreds of miles and sending shockwaves that would shake buildings and break windows in the small but booming city of Las Vegas only 75 miles to the south. When I moved here at the age of six, testing had moved underground. Still, I remember the rattle on the window and the feeling of impending doom.

It never stopped. Now we have the war in Ukraine and a man with his finger on the button. All of us are afraid a bad day or a migraine will be enough for him to press it. I suppose that’s what ultimately drove me to tell this story, that sense of being unsafe and the danger of security. Along the way, I struggled with other notions like What makes us who we are? Is it where or when we are born? Klaus Fuchs and Julian Rosenberg would have probably said no to the former and, most likely, yes to the latter. It’s a complicated question, one that the central characters in my novel grapple with. One is nearing the end of his life while the other is halfway through his. Both have worn the uniform of their country. Both have done the bidding of others. In the end, the only important question that remains is when everything is on the line, do we have what it takes to do the right thing?

I hope you’ll come along to find out.

***