Oregon is a land for the white man, and refusing the toleration of negroes in our midst as slaves, we rightly and for a yet stronger reason, prohibit them from coming to us as free negro vagabonds.

—“ALL HAIL! THE STATE OF OREGON,”

Oregon Weekly Times, Portland, Oregon, November 14, 1857

The road is muddy. Puddles swell and shimmer. The crying jag left me hollow as a shell casing. Max navigates roads I can’t see save for rain scattering like shattered crystal, humming with his hat pulled low. Finally, he into a side street littered with broken bottles and cracked bricks. A featureless door confronts us, as does the happy stink of fry grease.

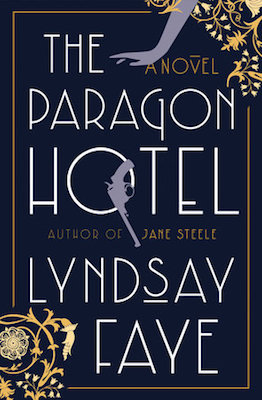

“Miss James, welcome to the Paragon Hotel.” Max pushes his way through.

We’re in a clean, spacious kitchen with a white‑and‑black tiled floor and copper pots hanging from the ceiling. An extraordinarily thin colored woman with biceps like braided rope and a red kerchief tied ’round her hair marvels at us.

“Maximilian Burton, who do you got there, and what are you doing in my kitchen with her?” she demands.

“Miss Christina.” Max makes a little bow without letting go of me. “Don’t you look swell this morning? I’d stay and chat, but I needs to get Miss James here to a room.”

Thunking a spoon against the pot she tends, Miss Christina crosses her arms over her chest, hunching as if to see me better. She must be well over thirty, but her small size lends her a youthful quality. She’s lean jawed and plain but very lively—the sort who make out spectacularly as flappers, with a few spangles and an artful smear of lipstick—and she appears to suppose I’m some kind of cheap floozy when really I’m an awfully expensive thug.

The fried fish I smell sits on a wire rack, a staff meal for the maids and the doormen. It’s so familiar, it’s heartbreaking—I’ve lived in hotels for my entire life, I know how they operate just before dawn. Bread rises in the oven and beans bubble in the pot with some sort of pork oozing into them. I wonder when I last ate and can’t recall.

“Oh, she needs a room, does she?” Miss Christina’s face screws up. “And whoever done heard of a stray cat, not to mention a white one, following you home, Max?”

“There’s this type of situation known as an emergency,” he hisses. “Oh, you figure?”

“Yeah, I figure.”

“Your emergency, is it, personally?”

“How many crises you suppose you’ve handled without a direct stake, Miss Christina?”

“My share. But you ain’t right in the head if you figure we can take her in, things bad as they are. She’s unlucky.”

“So’s a white girl’s corpse in one of my sleeper cars. What’s your opinion on broken mirrors?”

Her eyes widen. She shouts out the kitchen door for help.

Rainbow spots dart to and fro across my vision. Before I can be so bold as to request a chair, a sturdy blue‑black matron charges in with a prim, pretty maid and a pair of half‑dressed bellhops who gape at me with varying levels of astonishment.

Then every eye flies to the older woman. As if she’s a high priestess or a queen, possibly both.

“Max, child, there had better be an explanation forthcoming, and I mean at this very moment,” the woman drawls with a peach‑dripping Georgia accent.

“I done found her in Chicago and was with her on the Denver leg, barely able to move from her bunk. She’s from Harlem. We can’t let her die alone on a train platform,” Max bites out. “Someone hurt her, bad. I can’t tell if it’s lady troubles or—”

A storm of activity interrupts him. People call out instructions, feet vibrating through the tiles of the kitchen floor. I can feel this with marvelous accuracy because I’m on the kitchen floor. The back of my head is cold. There isn’t one place that hurts any longer, there are only vibrating waves of please stop, and I’ve lost the reason this is happening to me.

Probably for the best.

When the bellhops get back and a flat half‑assembled cot is wedged under my back, I do finally scream. And figure I’ll keep at it even though the matron is trying to hush me.

Next thing I know, I am indeed in a hotel room.

The chandelier is thick with metal leaves, the walls neatly papered. Petite cobalt flowers on a grey trellis. Squinting, I see a basin and pitcher, a desk, a sapphire chintz bench with a cushioned armrest, carved posts at the end of my bed.

My coat is gone, shoes missing, and my dress half shrugged off me. A man’s unsteady hands are setting the coverlet over my lower half.

Then they’re lifting my chemise and I push them away.

“No!” I snarl.

If you ever must see a doctor in an emergency, you see one in our pay, or who knows how fast you would be in the Hudson, my dear young lady, a well‑remembered voice that can’t protect me anymore says in my head.

“Miss James, I think is your name?” a gravelly rasp inquires. “Or so Max tells us. I don’t really give a damn what your name is, but I am a physician and must adjust your underthings.”

Blinking, I try to understand what sort of fellow I’m looking at. It’s not exactly duck soup. His face is pale mulatto and as blanketed in freckles as New York summers are populated with mosquitoes. His irises are green, peering from behind what some would call spectacles and I’d call a set of awfully sturdy beer steins. Wirebrush grey hair bristles from his pate. I smell cheap whiskey, a sweet‑sour cloud, which may or may not be emanating from him. Since he wears only a robe and pajamas, he either resides at the hotel or else doesn’t plan on running for public office.

“All right, I’m Miss James, then.”

“Dr. Doddridge B. Pendleton. Whether or not you are in fact Miss James—as I said, I don’t give a damn.”

“I’m awfully sorry to be so much trouble.”

“Trouble is the nature of my profession.”

“Where’s Max?”

“Sugar, this ain’t the time for a wide audience, agreed?” The matron sits on the end of the bed. Her thick hair is braided in proud hulking coils, upswept, and streaked with pewter. An upside‑down tornado. “I calculate you’re wary of strangers, but so are we, and I can vouch for the doctor’s character. Now. Is it lady trouble?”

A pause. Recalling I’m going to die, I lift my chemise myself. “It’s twenty‑five‑caliber trouble.”

The twin wounds have turned monstrous. Fire‑breathing dragons guarding a horde.

The twin wounds have turned monstrous. Fire‑breathing dragons guarding a horde.Dr. Pendleton slides his glasses up and down his nose like a trombone. He exchanges a grim look with the matron, who shakes her head.

Tension spreads in spider‑silk patterns, fans weblike throughout the room. The vote against my being here seems unanimous so far, saving only Max. I’m not brainless enough to think we’re in Harlem, but from their faces, this is the moss‑draped heart of Jim Crow Missouri with a right jolly banjo strumming in the distance. Not a Northern port city.

“Miss James, was this done by accident?”

Animal fear parches my throat at the slightest reference to Nicolo Benenati.

“Of course it was an accident,” I grate. “This is what happens when a silly girl takes up with a real rat, and I’m paying the piper now. He was drunk, he’s always drunk, God, and he’d spilled me enough times before that I hated the thought of visiting the carpet again. So I ran, and I think he meant to scare me. He always says he loves me when it’s over, but after this—can’t you see? I could have died.”

That’s an old story, and a good one.

Dr. Pendleton blows air past his lips, and yes, the liquor per‑ fume is definitely his brand. “Is this man likely to follow you here? Truthfully, now.”

I force a laugh. “Not in his state—he passed out cold as an ice‑box. Missed me playing Red Cross, me packing, the whole onion. Doc, I never meant to get Max in hot water. He rescued me, and I didn’t have a vote. He seems dreadfully headstrong.”

“Does he now?” the matron drawls. The woman owns about as much gravitas as a mountain, and is roughly the same shape.

“Yes. I think his friends should watch out for that tendency in his character. Now, are you going to toss me street side, or patch the old girl up? When he said I was dying, I’m . . . pretty sure he had the right idea.”

This evaluation is made through the last of my exhausted tears.

Dr. Pendleton whisks his glasses off. “Oh, I was always going to patch you up. It doesn’t matter whether I like a patient or not, or what race they are—I’ve taken a sacred oath. Which is lucky for you, since I don’t like you being here at all.”

“Um . . . thank you?”

He produces a vial and pours a smidge of liquid into a kerchief. “Miss James, I aim to close these apertures. Your blood has been severely poisoned, but you are not yet fully in the grip of sepsis. It’s my belief that you cannot stay still for such a painful procedure. If I give you this chloroform, I admit there is a minor chance you may not wake up—but if you do not allow me to treat you, you certainly will not survive. It would be unethical for me not to mention it.”

My lips part as I absorb this.

But there’s only the ceiling above me and a chandelier to address. I’d say goodbye to the hotel room, but it’s unfamiliar. I’d say goodbye to Max, but he’s done enough already, so much that it lodges in my throat like a sweet thorn.

I’ d say goodbye to myself, but we lost touch a very long time ago.

“When you put it like that,” I reply, and reach up to pull his handkerchief down to my nose.

At first, there is only afternoon light gilding my blond lashes.

It’s pleasant. I take care not to stir.

Calm. Stay calm.

Something chemical is happening, something familiar. It’s not laudanum, I’m fairly certain. If it were heroin, I wouldn’t recognize it. The hurt radiating from my side feels like it’s locked in a display case. Not gone, not even hidden, just trapped. Therefore, probably morphine.

__________________________________