Hercule Poirot famously said, “I do not approve of murder.” And with good reason. A murder is a bomb that blows up the delicate matchstick house we call “civilization,” driving shrapnel into everyone and everything it touches. A murderer kills more than a person; he destroys the social contract founded on the most important commandment: Thou Shalt Not Kill. A murder is a tear in the social contract, but it’s also a gash in the landscape in which the body is found—because a murder is inextricable from the landscape it’s committed in.

Detective fiction is a highly structured, satisfyingly codified means of exposing the depths of human darkness. The killer and the detective form two legs of a crime novel’s essential tripod, the other being, of course, the victim, who is dead, and whose body is the fact around which killer and investigator do their riveting, seductive, dangerous pas de deux. We stay with them in lockstep until the truth is uncovered—the aha! moment of total surprise that is the payoff of the story. It’s a classic formula. It never gets old.

Over decades of reading hundreds of detective novels, I’ve always gravitated to three places that are uniquely conducive to a murder-mystery series: Scandinavia, England, and the desert of the American Southwest, most often southern California. For different reasons, with apologies to New Jersey (Janet Evanovich), Chicago (Sara Paretsky), Scotland (Ann Cleves) and Miami (Carl Hiaasen), these three locales consistently host some of the best crime-fiction series around. Of course, all murder-lit fans have their favorites—mine are Nesbø and Mankell in Scandinavia; Christie, Sayers, and Francis in England; and Chandler and Grafton in Southern California.

Each place has a different kind of detective, a different flavor of killing. Harry Hole and Kurt Wallender, the detectives of the series by Jo Nesbø and Henning Mankell, might be loose cannons with idiosyncratic methods, but they’re also solidly embedded in their respective police forces as citizens of socialist, tolerant countries. They’re outsiders and loners by nature, not by trade. They work methodically, gloomily, doggedly going wherever the clues take them, driving silent miles through twilit winter gloom to remote farmhouses where bodies lie shattered, drenched in blood. Scandinavian crime fiction is like no other country’s, and its geography is a large part of what makes it so thrillingly dark and twisted.

Of these three locales, Nordic noir is the grisliest, the most appallingly (wonderfully) grim, which befits the windswept, dark, snow-driven expanses of Sweden and Norway, the deep, rocky fjords and the cold, wild seas: Baltic, Norwegian, and North. Maybe because the landscape is so desolate and bleak, the Scandinavian folk-soul seems to have an insatiable appetite for very fucked-up murders–the old stories of the Nordic gods are equally violent, incestuous, irrational. And there’s a weary resignation in Scandinavian detectives, a tacit acknowledgment that violence and the past are always with us.

The great British whodunnit series of Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Dick Francis are, by contrast, distinguished by plots that are cerebral and clever, with detectives who are intellectual, genteel, and preternaturally observant. A murder in the U.K. is, first and foremost, a shocking affront to society, and British detectives are traditionally securely attached to the green, small island they inhabit, its tightly knit milieus of universities, vicarages, small country villages, universities, and horse racing. They operate in small, enclosed spaces, formidable brains alight. They’re all understandably nonplused by murder, and they find themselves embroiled in detective work by circumstance, not chosen profession.

Sayers’s Lord Peter Whimsey, Christie’s Miss Marple, and Francis’s intelligent, well-intentioned jockeys are all upstanding members of their microcosms: they’re notably not outsiders, not loners. In well-tended lanes lined with clipped hedgerows, formal drawing rooms redolent of lavender, servant-filled kitchens where cooks brandish rolling pins and ladles, Marple and Whimsey and Francis’s various lean, hungry jockeys avidly pursue the person who so outrageously defied the strictly codified conventions of British life by committing something as gauche and outrageous as a murder. They approach crime solving with pragmatic determination, butlers going around with brooms and dustpans, cleaning up the unsightly, unseemly mess of a dead body. They find the killer through deduction, social cues, and many cups of tea. A British murder is skin to a cryptic crossword puzzle. If the solver keeps at it, working out the clues, it all becomes clear.

California desert noir is saturated with a sun-drenched, glamorous overlay, but there’s a dark, seamy, neon-streaked underbelly, and we never forget it. These books are all about style: a murderer has a signature method; a detective has attitude, grit, and a laconic, sardonic way with words; the victim is often someone dramatically, colorfully complicated. And the setting is the flat, seemingly open world of beach and desert, wide palm-lined streets, unhappy rich people in Spanish-style villas up winding canyon roads.

Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlow and Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone are arguably descendants of the outlaw, that great American romantic figure, as much as they are of the Wild West sheriffs who pursued them. Out west, it’s always been hard to tell the difference between law and outlaw.

Desert-rat private eyes run their own agencies in rented offices. They’re not cops, they’re subversive renegades who relish stakeouts, break-ins, snooping in locked filing cabinets in dark offices, safe cracking. They swashbuckle around the gray areas of the law, driving the dark back roads alone, whipping out their guns in shadowy alleyways, eschewing the weakness of human warmth. Above all other techniques, beyond their grit and moxie and stubborn, nosy determination, they solve their murders by thinking like the criminal they’re chasing. Southwestern detectives are aligned with killers in a deep, subterranean way.

One of the primary reasons these three great traditions are so consistently popular is that they’re rooted in and distinguished by their place and setting. A murder in Scandinavia is different from a murder in California or England. It means something different, it feels different, and its solutions are different. I read (and love) these series as much for culture and place as plot.

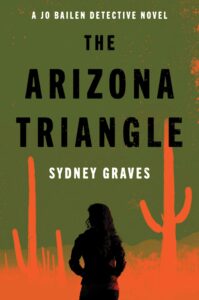

This month, I’m publishing my own detective novel, the first in what I hope will be a series. Set in and around Tucson, The Arizona Triangle owes a debt to all the great desert noir that preceded and inspired it. As I wrote, I found myself sliding easily into a warm, well-worn tradition: sun-splashed desert, hot and bright, in which everything wants to kill you; a hardboiled voice that masks a vulnerable soul; a murderer whose methods have a signature style, a triangle etched onto the victims’ forearms. I used the familiar but strange landscape and atmosphere of Arizona, where I grew up, as a detailed canvas, a painted screen, on which the drama played out.

Arizona has a peculiar quality: the tacky temporariness of Anglo culture is clumsily stuck onto the ancient history of the indigenous tribes for whom the rocks and plants were sacred, alive. What, I asked myself as I wrote the book, is the import of a murder of a white person in such a place, where most of the indigenous people were slaughtered and displaced? What does murder mean here?

A murder mystery is a question, above all, of location. Why, how, when, and who are found by understanding where.

***