Part 1: The Playboy

Detective fiction of the Golden Age (roughly 1920 to 1940) is known for the glimpses it affords readers of the rarefied world of leisured wealth. Yet the clever scribblers who produced those charming tales of classical detection during the years between the two world wars typically drew inspiration more from their vivid imaginations than from real life. For most writers of the period (not to mention most readers), the old moneyed and sophisticated coterie of Peter Wimsey and Philo Vance, who with sublime self-confidence exquisitely swanked their well-bred ways though the gilded pages of Golden Age mysteries, were winsome figments of romantic fantasy. William Willoughby Sharp, however, was an author of Golden Age detective fiction who actually lived the sort of life that Dorothy L. Sayers, S. S. Van Dine and many others wrote about in their books. (So did S. S. Van Dine, for a time, on the backs of his bestselling mysteries.) Moreover, like the privileged gentleman amateur sleuths of fiction, Sharp would encounter a mysterious murder—in this case the murder of his “golden boy” publisher, Claude Kendall. In contrast with fictional Golden Age mysteries, however, what might be termed The Claude Kendall Murder Case would remain unsolved.

Although Willoughby Sharp was born in New York City, at the time of his birth on June 13, 1900 his ancestors had been prominent in the city of Norfolk, Virginia, for a century. His grandfather was a United States Naval Academy graduate who commanded the Confederate gunboats Beaufort and Neuse during the Civil War and headed the Confederate Naval Ordnance Department, while his great-grandfather was a Norfolk attorney and the president of the city’s Exchange Bank. In the 1890s Willoughby Sharp’s father, William Willoughby Sharp, Sr., relocated from Norfolk to New York City, where he worked as a clerk in the office of famed financier J. P. Morgan. Starting his own firm on the strength of a loan from the Great Man himself, the senior Sharp became a wealthy and, rarer yet, highly respected stockbroker, joined the Calumet Club and was listed on the Social Register. He married Dora Adams Hopkins, a beautiful young widow of distinguished antecedents originally from Atlanta, and the couple had three children, Willoughby and two daughters. In the Twenties the family was served at home by five live-in servants: a cook, laundress and three maids. When in 1926 the elder Sharp, who had had held his seat on the Stock Exchange for three decades, was hit and killed by a taxicab as he crossed West Eleventh Street, Greenwich Village, he was returning to one of those elegant brownstone row houses that served as sites of fiendish slayings in Philo Vance’s murder cases.

Like the privileged gentleman amateur sleuths of fiction, Sharp would encounter a mysterious murder—in this case the murder of his “golden boy” publisher, Claude Kendall.Indicating the social standing of Willoughby Sharp, Sr. in New York, one daughter married Gilbert Eliott, a stockbroker and heir presumptive to a baronetcy, while another wed Russell Grace D’Oench, the son of Albert Frederic D’Oench and Alice Grace, a daughter of William Russell Grace, the fabulously wealthy former New York mayor and founder of the great chemical conglomerate W. R. Grace and Company. Russell “Derry” D’Oench, scion of the Sharp-D’Oench union, wed Ellen “Puffin” Gates, a Vassar College classmate of Jacqueline Bouvier. Their impending nuptials inspired the future spouse of John F. Kennedy and First Lady of the nation to compose a poem in tribute to her friend, the first lines of which run: “Puffin and Derry in wedded bliss soon will be/Vassar will miss her and so will we.”

Derry’s uncle, the younger William Willoughby Sharp, in New Hampshire attended the elite St. Paul’s School, where he played football and served as assistant editor on the school magazine, Horae Scholasticae. Already displaying a literary bent, Sharp during 1917-18 contributed to Horae Scholasticae poetry of a higher order than that which Jacqueline Bouvier later penned in praise of lovebirds Puffin and Derry. Lines from Sharp’s “Changing Colors” suggest his early interest in the maritime world and foreshadow the setting of his first detective novel, Murder in Bermuda: “Rosy coral and black rock shells/Lay where the gleaming sun-fish glide/’Mid crimson sea-flowers and violet stones/Where carmine conchs and blue crabs hide/In the depths of the tossing sea.”

With the entry of the United States into the Great War, however, martial images predictably came to fore in the young man’s poetry. The teenager put his words into action not long after his eighteenth birthday on June 13, enlisting in the United States Marine Corps, although prosaically he spent the war not in the vicinity of Paris, France, but rather at the Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina.

Upon his release from the army in 1919, Sharp matriculated at Harvard, where for a couple of years he studied English literature. During this time he also wrote some crime stories for the pulps. One of Sharp’s stories, “Dead Men Tell No Tales: A Story of Circumstantial Evidence,” which originally appeared in Munsey’s Magazine in June 1921, is a dramatic tale of the trial of a pathetic clerk for the murder of his employer. It dared to suggest to Munsey’s readers that lady justice can be a capricious creature. Had time already blunted the youthful naive idealism to which Sharp had given voice in his prep school poetry?

***

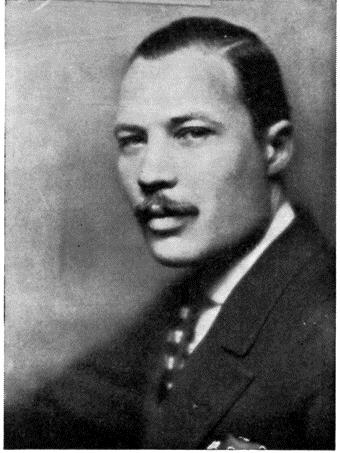

After taking leave of Harvard, the handsome veteran returned to New York, where he became a fixture in café society. For much of the Roaring Twenties, a decade which apotheosized on film the sex appeal of such magnetic “Latin lovers” as Rudolf Valentino and Ramon Navarro, Sharp, with his tall, lean, muscular frame, sculpted, darkly handsome face and suave mustache lived like the elegant young man-about-town of detective fiction fame. Giving us a glimpse of his life at this time is a 1922 altercation in which he was involved at the fashionable Club du Montmartre, which made the pages of the New York Times. The Montmartre was a late-night supper restaurant, located at Broadway and Fiftieth Street, that F. Scott Fitzgerald in “My Lost City” later recalled as the “the smart place to dance” in Twenties New York. The popular club, which earlier that year had been fruitlessly raided by Federal Prohibition agents, was evocatively portrayed in this wryly cynical 1923 article in The Smart Set, the quintessential Jazz Age literary magazine, by modernist painter Charles Green Shaw, titled “11: 30 to 3:00 (A Textbook for Students of Insomnia)”:

“Broadway, Fifth Avenue, Wall Street, the upper West Side, Hollywood and Princeton are all represented [at the Club du Montmartre]; there is a touch of the stage, of society, of sport. One sees oil magnates and sopranos, dowagers and chorus girls, debutantes and press agents. One sees ex-husbands and ex-wives, in the arms of more sympathetic partners, buffeting each other on the dance floor. One sees sexagenarians supping flappers in their teens, and across the room, their sophisticated sons making merry with more matronly damsels.”

Accompanied by friends John Magee “Jack” Boissevain, a former classmate from St. Paul’s and son of the president of Hilliard Hotel Company, and Louis Frederick Bertschmann, son of one of the co-founders of the Bertschmann & Maloy insurance brokerage firm, Sharp at around three in the morning left a dance at the Hotel Vanderbilt (part of the Hilliard Hotel chain), in order to join a supper party being given at the Montmartre by their pal Henry Rau, son of a Staten Island wood pulp importer. “A lot of nice people were there, including Prince Engalitcheff,” Sharp confided to the New York Times reporter who came to interview him at his parents’ brownstone to get his side of the story, name-dropping a prominent White Russian fellow broker and a drinking buddy of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. (“We came to New York and rented a house when we were tight,” Zelda reminisced to Scott in a rambling stream-of-consciousness 1930 letter. “There was Val Engelicheff [sic] and Ted Paramour and dinner with Bunny [Edmund Wilson] in Washington Square and pills and Doctor Lackin and we had a violent quarrel on the train going back, I don’t remember why.”)

Unfortunately for young Sharp and his two chums, who were just looking to have a happy time, the Montmartre doorman truculently denied them admittance, claiming that the club had closed, though in fact Rau and his gang were still partying. When the doorman tried to shut the door in their faces, Jack Boissevain inserted his cane between the door and its frame, allowing the fun seeking trio to push through the portal into the entrance hall. The doorman, according to Sharp, responded by punching Boissevain and then punching Sharp, “very hard.” “Naturally,” Sharp loftily declared to the Times reporter, “we were not looking for any such treatment in a place that caters to ladies and gentlemen, so that we were taken by surprise.”

Sharp went down on the floor, where he was held by the two Montmartre elevator operators while the doorman continued to punch him, giving him a black eye and a bloody nose. Extricating themselves from the affray, the three young men alerted the police, but by the time a sergeant and four policemen had arrived at the scene of the late battle, the doorman, scenting which way the wind blew, had fled from the premises. “Propped up in bed…with a piece of gauze covering his injured nose but failing to conceal his black eye,” Sharp explained that he had been moved to speak out publicly about the incident “not on my own account, but because of the example, and because this is not the first time the same kind of thing has happened there [at the Montmartre].”

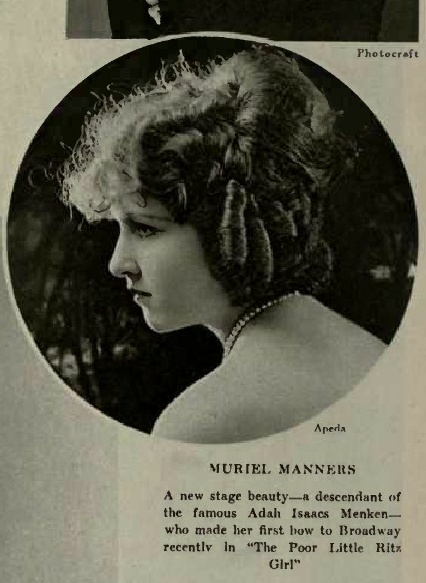

Willoughby Sharp garnered public sympathy over what a mystery writer might have called The Mysterious Affair at the Club du Montmartre, but he scandalized his mother and sisters when in 1930 he married his twenty-four-year-old companion, Muriel Manners, a divorced former Ziegfeld Follies chorus girl from Jackson Heights, Queens. The daughter of a Broadway producer, Muriel Manners claimed lineal descent, through her mother, from the mid-nineteenth-century actress, poet and essayist Adah Isaacs Menken (1835-1868), who was of mixed race parentage. Menken, who was probably originally named Adah Bertha Theodore, was a celebrated Victorian-era actress who had come to know many of the literary luminaries of her age, including Charles Dickens, Charles Swinburne, Alexandre Dumas and Walt Whitman, and shortly before her death had published a book of poetry, Infelicia, which she dedicated to Dickens. Menken’s sons having died in infancy, however, possibly Muriel Manners, whose mother was Janet (Menken) MacMahon Manners, was instead descended from the family of Alexander Isaac Menken, a Jewish musician who had been Adah’s first husband. In any event, there doubtless was much of which to disapprove about Muriel Manners for a WASPish Social Register family like the Sharps, whatever skeletons their own closets might have held.

Despite opposition from his kinswomen, Sharp’s union with Muriel Manners was a decidedly happy merger of kindred souls, eventually producing four children, a son and three daughters. Already Sharp had ceased dabbling in pulp fiction and in 1925 had become a member of the New York Stock Exchange, courtesy of his father, who a year before his death had gifted his fortunate son with a seat on the Exchange on the occasion of his twenty-fifth birthday. In 1928 Sharp with Dudley Harde and Dudley Brown Harde established the rather Dickensian-sounding brokerage firm of Harde & Sharp. The Sharps resided at a Park Avenue apartment with a bar that, most conveniently in the era of prohibition, could be folded in and out of a wall. Painted with lions and tigers (though no bears, naturally), it was dubbed the Circus Bar. Here the couple kept what their son, the late avant-garde artist Willoughby Sharp, described as “a kind of open house,” entertaining “their friends and friends of friends and friends of friends of friends.”

***

Of course the great party was destined to come to a halt with the stock market crash. Sharp’s son recalled that his father mordantly told him concerning this period in history that upon leaving his office at One Wall Street he always would look “up over his shoulder…in fear of being hit by people who jumped to their death from the building.” In 1931 Sharp, not liking the outlook on Wall Street, sold his seat on the Stock Exchange and moved with Muriel to the island of Bermuda, a popular vacation destination during the Thirties for Eastern Seaboard socialites. There the couple lived off the sale of costly pieces of jewelry which Sharp had bought Muriel back in their champagne days. After a couple of years in Bermuda, Sharp felt inspired to compose his first detective novel, in which he imagined foul play taking place on the fair island. Predictably enough, he titled the novel Murder in Bermuda (1933). Sharp completed his second mystery, Murder of the Honest Broker (1934), in Bermuda as well, but he edited the proofs over the summer of 1934 while staying at New York’s Calumet Club. After the publication of Murder of the Honest Broker in August, he and Muriel returned to New York to stay.

Published in the United States, England and Germany, Sharp’s pair of detective novels proved excellent sellers—although a financial hitch occurred in Germany, when authorities in the lately installed government of Adolf Hitler, following the Nazi policy of autarky (i.e., economic self-sufficiency), refused to export to the U. S. monies due on the first three printings of Murder in Bermuda. Finally the parties agreed that the book’s German publishers would remit payment “in kind—kind in this instance being 100 cases of the finest Rhine wines.” At the end of the year, Sharp entered into a publishing partnership with a fellow New Yorker, Claude Henry Kendall, the man who had produced his two detective novels in the United States. Perhaps the new partners, unaware that one of them would be dead in under three years, celebrated the occasion with a bottle of fine Rhine wine.

****

Part II: The Publisher

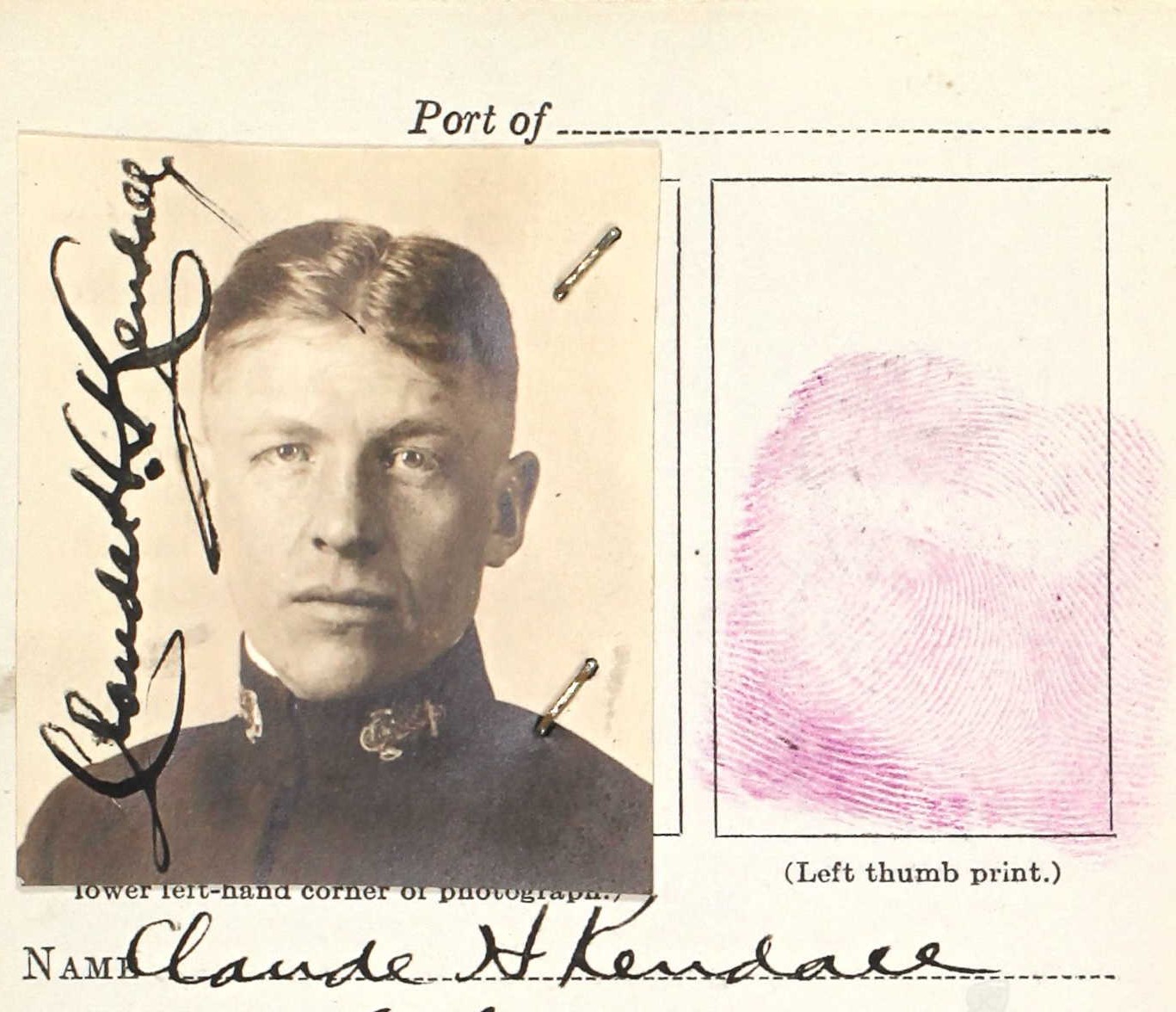

Although largely forgotten today, the publishing firm of Claude Kendall was a notable business venture that sprang up and managed to thrive for a time amid the ravages of the Great Depression. Older than Sharp by a decade, Claude Kendall, the eponymous individual behind the company, was born in 1890 in the small city of Watertown, located in northwestern New York, near Lake Ontario. He was one of four sons (including his twin brother Fred) of Martin Kendall, a son of German immigrants who served as assistant superintendent at H. H. Babcock Company, one of the largest carriage manufacturers in the United States, and his wife Clara Ingalls, a farmer’s daughter. In Watertown young Claude was considered quite the live spark, working as a “carrier boy” (i.e., paperboy) from the age of ten and serving on the student council at the local high school. At the age of sixteen he was awarded the gold medal in an oratory contest sponsored by the New York chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Two years later, at his high school graduation ceremony, he was chosen to recite before the assembled audience of Watertown family and friends Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Claude Kendall began life in modest circumstances in an out-of-the-way corner of the world, but he soon moved on to bigger things in life. His ticket out of Watertown came when, after briefly working as a stenographer in a hardware company, he landed an administrative position at the Mount Washington Hotel, one of great turn-of-the-century grand resort hotels, located in the White Mountains at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. (The hotel would serve as the site of the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which established the International Monetary Fund.) There Kendall–short, blonde, blue-eyed and highly presentable in dress clothes–met investment banker M. H. Rice, who promptly hired Kendall as his personal secretary and took the young man with him to Europe for four months. After the pair returned to the United States, Kendall settled in New York City, where he was employed by Charles R. White & Co., an investment banking firm, and for two years attended New York University.

When the United States entered the Great War, Kendall enlisted in the navy and was commissioned an ensign. After the war he joined the United States Shipping Board as a supercargo officer, in which capacity he traveled to both Europe and East Asia. He then was hired by Standard Oil Company and spent five months representing the company’s interests in Tampico, Mexico. After this latest foray into foreign fields he was hired as a staff correspondent by the United Press and assigned to South America. Finally returning to New York in the late 1920s, Kendall charted an entirely new career course, founding his own publishing firm in 1929.

***

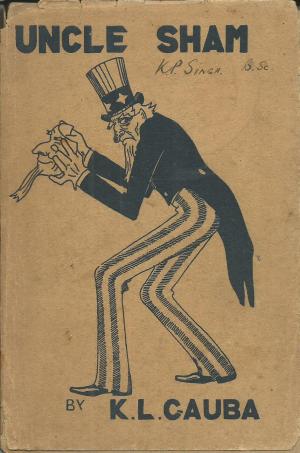

The first publication of Claude Kendall was Uncle Sham, a controversial critique of American culture by an Indian national, K. L. Gauba, who had been greatly incensed over the publication a couple of years earlier of Mother India, a book by an American author, Katherine Mayo, which was scathingly critical of India’s culture, particularly on account of the treatment of Indian women. The nettled Gauba responded in kind about the United States, often in frank and indelicate language, provoking the United States Customs Service to confiscate review copies of the book that had been sent from India to the United States, on the grounds that the writing was obscene. Having a keen nose for controversy, Kendall successfully published the book in the United States, putting his nascent company on the publishing map with a fine flush of notoriety. Uncle Sham’s dust jacket blurb boasted that Gauba’s book revealed the “pools of nastiness, obscenity and vice” underlying “the smug morality of the United States.” Curious readers—many of whom likely had never even stuck their toes in the water, so to speak—wanted at least to glimpse these teeming pools.

Uncle Sham sold well, quickly going through several printings. Claude Kendall quickly followed Uncle Sham with a second opportunistic publication of a work scoring off a notorious book of the moment: a second edition of Henry von Rhau’s The Hell of Loneliness, an “impudent and delightfully scampish” parody of Radclyffe Hall’s intensely serious landmark 1928 lesbian novel (then banned in England), The Well of Loneliness. “Henry von Rhau” was none other than Henry Rau, the man whose private party at the Club du Montmarte Willoughby Sharp and his friends had been excluded from entering by an overzealous doorman back in 1922. Like Claude Kendall, Rau, or “von Rhau” as he was now more loftily known, had worked in the oil business in Latin America after the war. Kendall’s edition of The Hell of Loneliness included illustrations by gay playwright John Colton, a friend of both von Rhau and Willoughby Sharp. (At von Rhau’s wedding Colton and Sharp had served as ushers.) In the Twenties and Thirties Colton achieved fame as the author of the sexually frank Far East dramas Rain (based on Somerset Maugham’s celebrated short story “Miss Thompson”) and The Shanghai Gesture as well as Nine Pine Street, a dramatization of the Lizzie Borden murder case that starred Lillian Gish.

Encouraged by his initial successful splash into book publishing, Claude Kendall over the next seven years produced a succession of what often were termed “spicy” or risqué books, attractively bound, printed and, frequently, illustrated. “[T]hough widely different in subject and scope, all [of Claude Kendall’s books] bear the definite stamp of the publisher’s individual taste,” wrote Madison, Wisconsin Capital Times reviewer Adelin Hohlfeld in a laudatory 1931 piece about the man and his product. “There is a touch of madness in all of them, combined with a verve and beauty and unusualness which make them wholly unlike most popular modern fiction….”

The most notorious and successful of the Claude Kendall books were four novels authored by Tiffany Ellsworth Thayer, aka “Tiffany Thayer.” With several hundred thousand copies sold during the early 1930s, the Tiffany Thayer novels, particularly Thirteen Men and Thirteen Women, earned Claude Kendall a great deal of publicity. Other controversial books from the early 1930s that bore the Kendall name include: the first American edition of Octave Mirbeau’s Torture Garden, a primary text of the Decadent Movement originally published in France in 1899, of which pulp writer Jack Woodford expressed his amazement that Claude Kendall had been able to publish its “splendid” edition (“I don’t see how it would be possible to write a more ‘dangerous’ book [from the standpoint of the censor] yet it was published.”); Mademoiselle de Maupin, an American edition of Théophile Gautier’s gender-bending 1835 novel about a real-life French cross-dresser; G. Sheila Donisthorpe’s Loveliest of Friends, a novel dealing with lesbianism; Cecil De Lenoir’s seedy The Hundredth Man: Confessions of a Drug Addict; Beth Brown’s Man and Wife, about prostitution and the divorce racket; Lionel Houser’s Lake of Fire, described as a “bizarre tale of identity theft, mutilation, lust and murder, provocatively illustrated with strikingly explicit woodcuts”; R. T. M. Scott’s, The Mad Monk, purportedly about the early life of Rasputin; Lo! and Wild Talents, two of Charles Fort’s bizarre collections of “anomalous phenomena”; and, last but not least, Frank Walford’s Twisted Clay, a lurid tale, recently reprinted, about a psychopathic, patricidal bisexual female serial killer that was banned by government authorities in both Canada and Australia. (“She loved…and killed…both men and women,” promised Twisted Clay’s salacious jacket blurb.)

Ever eager where controversy was concerned, Kendall also unsuccessfully attempted to secure the American publication rights for James Joyce’s Ulysses, which had been banned in the United States on obscenity grounds since 1920. Sylvia Beach, the publisher in France of Ulysses, demanded from Kendall $25,000 for the novel’s American publication rights, a figure that Kendall termed “absurd.” Kendall doubted he could recoup the cost of both a $25,000 payment to Beach and the inevitable litigation over the novel in American courts. Certainly Kendall had to reckon with the reality of potential legal action: Thirteen Men, Twisted Clay and Loveliest of Friends, for example, all had been banned in Canada, a trifecta of casualties to conventional moral outrage.

***

Like its star author Tiffany Thayer, whose books F. Scott Fitzgerald—no Puritan he—disparaged as “slime…in the drug-store libraries,” the firm of Claude Kendall clearly has developed something of a reputation. Newspaper notices that Claude Kendall books received in the 1930s often emphasized what was deemed decidedly racy subject matter. Middle American reviewers seem to have been especially scandalized. One such individual in Greensburg, Indiana deemed Thayer’s Thirteen Men “morbid” and complained that “not even the Russians could pack more unhappiness in a single volume.” In Salt Lake City, a reviewer for the Deseret News observed sardonically that Roswell Williams’ The Loves of Lo Foh “will never be discussed at a ladies literary tea” and was “hardly suitable for the entertainment or education of budding youth.” An especially incensed Midwestern reviewer for the Lawrence, Kansas Journal-World huffed that Tiffany Thayer’s An American Girl was “an obscene novel without any merit whatever” and that Beth Brown’s Man and Wife was “a worthless novel without any point or reason.”

Like its star author Tiffany Thayer, whose books F. Scott Fitzgerald—no Puritan he—disparaged as “slime…in the drug-store libraries,” the firm of Claude Kendall clearly has developed something of a reputation.For his part, Walter Stanley Campbell—a University of Oklahoma English professor who was Oklahoma’s first Rhodes scholar and, under the pseudonym Stanley Vestal, a prolific author of books and articles on the Old West (he even published a mystery, The Wine Room Murder, in 1935)—in the Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman wrote sourly of Alan Lampe’s A Torch to Burn that it was “another of the spicy novels for which the firm [Claude Kendall] is known….of course the adventures are sad, gay and mad. Those who find night-clubs exciting will probably like this book.” Similarly, Kenneth C. Kaufman—editor of the literary page of the Daily Oklahoman, a professor in the University of Oklahoma foreign languages department and mentor of closeted gay Choctaw detective novelist Todd Downing—primly noted that the protagonist of Frank Walford’s Twisted Clay was “a young girl, a homosexual, who…indulges in all sorts of sexual experiments, of which the less said the better….it just happens that I am not interested in sexual abnormalities.”

On the other hand, some reviewers savored the spice in Claude Kendall books. A reviewer for the Providence Journal deemed Thirteen Men “a masterpiece of our time.” Adelin Hohlfeld found the illustrations in pacifist Arthur Wragg’s Psalms of Modern Life, a book which ironically juxtaposed stately biblical verse with depictions of discordant twentieth life, “fascinating and terrifying” and the text of Sheila Donisthorpe’s Loveliest of Friends a “delicate and exotically sophisticated” evocation of a lesbian relationship. In California’s Sausalito News Edwin T. Gandy pronounced Wilson Collison’s slick courtroom melodrama The Second Mrs. Lynton “engaging,” adding that “murder, dramatic situations and witty dialogue are among the attractions in this tale already scheduled for talkie production.”

With justification the successful, attention grabbing publisher employed this bluntly boastful advertising motto:

Claude Kendall

Books That Sell

Verily, money is its own reward, and as the cash collected in his coffers Claude Kendall remained cheerfully sanguine about the stones which hostile critics cast at the books his firm published. Of the Kendall novel Tangled Wives (written by divorced journalist Peggy Shane), for example, Kendall bluntly pronounced: “It is not the great American novel; it is, however, swell entertainment.” In those rental libraries dotting America that F. Scott Fitzgerald so witheringly disparaged, people crowded in the aisles to borrow Claude Kendall books. The rapidly prospering publisher established digs in a luxurious Manhattan penthouse apartment—one formerly occupied, newspapers were wont to note, by famed actress Ethel Barrymore.

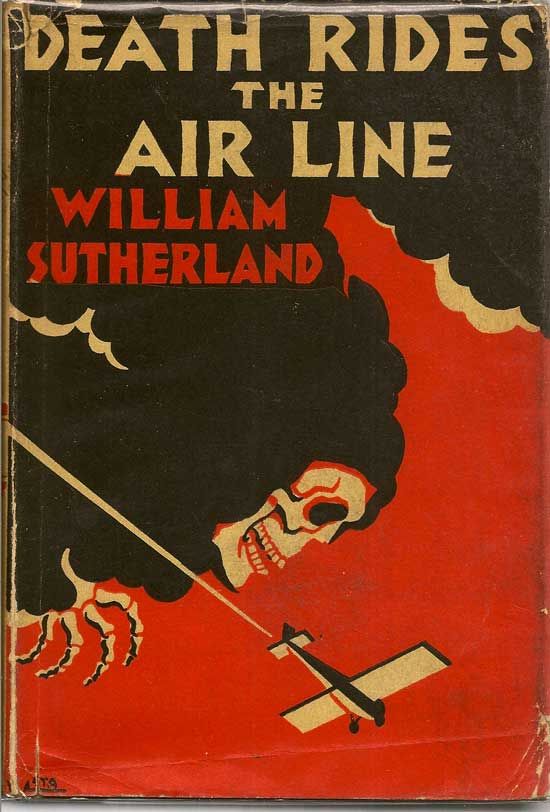

In comparison with Claude Kendall’s more risqué and attention-grabbing mainstream books, the detective and mystery fiction that the firm published offered subtler attractions. Besides the detective novels of Willoughby Sharp, books on the Claude Kendall mystery list included Andrew Soutar’s Secret Ways, J. R. Wilmot’s Death in the Theater, David Whitelaw’s Murder Calling and William Sutherland’s Death Rides the Air Line. All these titles seem originally to have appeared in England and were published by Claude Kendall in the fall and winter of 1934. All are competent pieces of mystery fiction, though only the Sutherland novel, with its unique plot structure and somewhat unsavory subject matter, departs from traditional Golden Age mystery norms.

Willoughby Sharp did not formally enter into Claude Kendall & Willoughby Sharp, Inc., his publishing partnership with Claude Kendall, until November 1934, yet he likely influenced Kendall’s selection of mystery titles during the latter half of that year. Additionally, Sharp was scheduled to publish with Kendall & Sharp a third detective novel, The Mystery of the Multiplying Mules, in 1935. However, this novel never appeared, nor does Kendall & Sharp seem to have published any additional true mysteries over the scant sixteen months of its existence, despite the company’s intriguing announcement in March 1936 that it was planning, presumably under Sharp’s supervision, a monthly series of detective novels, to be released under a new imprint, the Clue Chasers Club (clearly inspired by Doubleday, Doran’s highly successful Crime Club). It seemed there was always more money to be made out of mysteries.

In point of fact, Sharp with unknown motivation sundered his relationship with Kendall & Sharp mere weeks after the March 1936 announcement about the formation of the Clue Chasers Club. Possibly Kendall, with his grand ambitions and gross excesses (which likely included worsening alcohol addiction), had perilously overextended his firm, all the while having failed to duplicate his initial successes. Without Sharp’s financial backing, the company, briefly renamed Claude Kendall, Inc., went bankrupt before the end of the year. Clearly Kendall had suffered a powerful blow to his fortunes, but he stayed on his feet and accepted a position as assistant editor with the publishing firm James T. White & Co. Tragically, however, the now formerly independent publisher was not long destined to survive his defunct creation.

***

Part III: The Murder

By 1937 Claude Kendall had vacated the Manhattan penthouse apartment once occupied by Ethel Barrymore and moved into a $7-a-week room (about $125 today) on the eighth floor of the Madison Hotel, located at 21 East Twenty-Seventh Street, just off Madison Avenue. Around 11:00 a.m. on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1937, a hotel maid entering the Kendall’s small, yellow-walled room found the fully clothed forty-seven-year-old bachelor dead on the floor, with a bed sheet loosely wrapped around his neck. Inspector Michael McDermott, who earlier that year had been in charge of the investigation into the mysterious stabbing of Municipal Court Justice John F. O’Neil, initially opined that Kendall’s death was accidental, there being no signs of robbery or violence–other than the damage to Kendall’s face, of course, which McDermott suggested might have been due simply to the dead man’s having drunkenly fallen out of bed.

This convenient theory soon was dashed, however, by New York’s Deputy Chief Medical Examiner, Thomas A. Gonzalez (co-author of Legal Medicine and Toxicology, a landmark twentieth-century American text on forensic medicine), who concluded that far from being accidental, Kendall’s death had resulted from a brutal “homicidal assault.” The dead man, Gonzalez reported, had been “beaten and kicked so savagely [that] he suffered multiple hemorrhages of the head, resulting is asphyxiation.” Kendall’s physical injuries included “one black eye, a laceration on the inside of the lip and a swollen jaw,” along with “hemorrhages of the right cheek” and lacerations below the knees—not the sort of injuries one would expect to have received from merely banging one’s head against the floor or a piece of furniture. Once the police understood that they were dealing with murder and accordingly traced Kendall’s movements on his last evening of life, they quickly espied a likely culprit and declared themselves, with sadly misplaced optimism, “confident…of an early arrest.”

Two friends of Kendall’s, John South, a resident of the hotel, and J. B. Reilly, had been drinking with Kendall the prior evening at a Thanksgiving eve party held on another floor of the hotel. Around midnight they had put the inebriated Kendall to bed, removing only his shoes, Kendall all the while inarticulately protesting that he wanted one more drink. At about 1:30 in the morning on Thanksgiving Day, Kendall had determinedly got up from bed and left the hotel, drunkenly declaring yet again that he wanted one more drink. He returned about two hours later, around 3:30 a.m., bringing with him an individual later described as a “slightly built youthful white man,” whom he took up to his room. Around 4:00 or 4:30 a.m., Richard Barry, a novelist and pulp fiction writer of adventure serials in Argosy who with his wife resided in the room directly above Kendall, began at short intervals hearing loud “thumping noises,” which he believed emanated from Kendall’s room. Ominously, these noises, which Barry had attributed to a heating pipe, continued for over half an hour.

Half a century after Stonewall, we are giving voice again to forgotten men like Claude Kendall, who through heinous crimes of hate suffered not only cruelly battered and broken bodies but, more unforgivably yet, the final indignity of exceptional lives effaced.The “slightly built youthful white man” was not observed leaving the premises by either the elevator operator or the hotel desk clerk, leaving the impression that, like a character in an impossible crime story, he had vanished into thin air after having methodically punched and kicked Kendall to death. One newspaper account referred to the mysterious young man as a “phantom-like slugger.” Another asserted that the youth was a “familiar figure in the Madison Square district where Kendall lived.” Today, of course, it is not hard to read between the circumspect lines of Thirties print media, where homosexuality was still the love that dared not speak its name, and surmise that the youthful habitué of Madison Square—the “slim man,” if you will—was a homicidally violent hustler. Yet despite having this clearly marked trail to follow, the New York police, after questioning over one hundred people in the area apparently lost the slim man’s scent, leaving him to slip unmolested into the void of time. Perhaps there was not much enthusiasm on the part of the police or of Kendall’s family—his surviving brothers and his seventy-eight-year-old widowed mother Clara—in pursuing an investigation which likely would have brought intense shame to the good people of Watertown, New York by revealing the unpardonable queerness of their prominent native son’s lifestyle.

In the stereotypical 1930s detective novel, where everything is ever-so-neatly and reassuringly explained at the end, Kendall’s murder would have been solved–though not by some invariably bumbling police inspector like, say, Michael McDermott, who proclaims obvious murder an accident, but rather by the murder victim’s dapper, sophisticated and oh-so wealthy dilettante friend, Willoughby Sharp. (The man even came supplied with a simply smashin’ amateur gentleman detective moniker, don’t you know.) And, to be sure, when he was interviewed about the grim affair by the press, Sharp did not hesitate to proffer advice to investigators. The detective novelist opined that the murder “undoubtedly” was the result of a robbery committed by the slim man who accompanied Kendall back to his hotel room; and he suggested that to find this elusive individual the police should make “a close check of the bars Claude frequented.” Like the newspapers deliberately leaving the truth between the lines, perhaps, Sharp explained that his ex-partner “was a gregarious person, liked to talk, and he was friendly and could make acquaintances easily.” In the end it was the newspapers that were left with the final word on the matter, summing up the whole case, tritely but perhaps inevitably, given the murdered man’s occupation, as being “as sinister a mystery as he [Claude Kendall] produced in book form.” When Willoughby Sharp passed away nearly two decades later at the age of fifty-five, the Claude Kendall mystery remained officially unsolved, as it still does today.

Onetime golden boy Claude Kendall, a publisher who seemingly had been endowed with the Midas touch, was left not just murdered and unavenged but ignominiously forgotten until 2013, when my blog posts at The Passing Tramp revived his name and Willoughby Sharp’s detective novels were reprinted by Coachwhip. A reprint by Salt Publishing of Claude Kendall’s single most controversial property, Twisted Clay, followed the next year. Five years after that, Kendall’s tragic demise, apparently an instance of one of history’s many fatal gay-bashings, was afforded two slim paragraphs in James Polchin’s Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice before Stonewall (2019), which powerfully chronicles the appalling history of twentieth-century violence against gay men in the United States. Today, half a century after Stonewall, we are giving voice again to forgotten men like Claude Kendall, who through heinous crimes of hate suffered not only cruelly battered and broken bodies but, more unforgivably yet, the final indignity of exceptional lives effaced.