Whether it’s the language, the tradecraft or the folk legends of American Mafia life, The Godfather reads like a voyage through the underworld with Mario Puzo acting as our Virgil.

The Godfather also functions as a classic of another genre: the immigrant story. Vito is the new arrival who works around the clock to establish himself in his new land, getting his hands dirty, while his more privileged and better-educated son longs to succeed like a native. Michael Corleone’s dreams are of assimilation. He marries a willowy WASP beauty, her family rooted in the New England of the Mayflower. He wears the uniform of the US Army. He is adamant that ‘his children would grow in a different world. They would be doctors, artists, scientists. Governors. Presidents. Anything at all.’

Naturally, these aspirations collide with the insistence on tradition that animates the founding generation. Don Corleone, his wife and their peers live in America but they are not of it. They still regard themselves as Italian. To see their children become absorbed by the new country brings pangs of loss for the old. Because they are a crime family, this nostalgia and respect for custom express themselves in unconventional ways. Witness Peter Clemenza, who trains Sonny in combat. ‘Sonny had no taste for the Italian rope, he was too Americanized. He preferred the simple, direct, impersonal Anglo-Saxon gun, which saddened Clemenza.’ There speaks the universal voice of the immigrant generation, worried that the old ways will be forgotten.

And yet that is far from the only twist on the conventional immigrant story. In American popular culture especially, the role of the immigrant is to love and revel in his new country, to embrace its values eagerly, to place his hand over his heart and grow moist-eyed at the sight of the flag to which he gratefully pledges his allegiance. Don Corleone refuses to follow that script.

On the contrary, he has no respect for America and actively disdains it. In one striking passage, Puzo tells us that Corleone profited from the war against Hitler as a black marketeer, that he helped young men dodge the draft by taking drugs before their army medical examinations, ensuring they would be deemed unfit for service, and that he was both astonished and furious to learn that men under his protective wing were volunteering to serve their country in uniform. ‘“This country has been good to me,”’ one of them tells his caporegime. The Don is appalled: ‘“I have been good to him,”’ is his response.

It must have taken a certain courage for Puzo, himself the son of Italian immigrants, to show his community in such a light, so far removed from the archetype of the grateful arrival, crossing his heart at the sight of the Statue of Liberty. True, the sins of the father are perhaps atoned for by the son, for Michael joins the war effort just as Puzo did. You can also make a case for the Corleones as the embodiment of American values, if not the American dream: they make a fortune through hard work, determination and industry, and they always put family first.

Still, none of this conceals the fact that Corleone Senior has no desire to fit in with America or be accepted by it, even though his youngest son seeks both those things. If anything, Vito Corleone believes he represents a superior moral order. Raised in a Sicily where the police are associated with the cruel, arbitrary power of ‘the landowning barons and the princes of the Catholic Church,’ he develops ‘contempt for authority and legal government’. As Michael explains to Kay of his father, ‘“He doesn’t accept the rules of society we live in because those rules would have condemned him to a life not suitable to a man like himself, a man of extraordinary force and character… In the meantime he operates on a code of ethics he considers far superior to the legal structures of society.”’

Puzo’s achievement is that we not only understand this of Vito Corleone, we come to agree with it. We sympathize with Bonasera the undertaker in his impotent fury when the courts allow the two youths who battered his daughter to walk free, and we cheer when Don Corleone metes out the justice which the system had denied. We feel the same impulse when Michael quietly makes his brother-in-law Carlo Rizzi pay for his own cruelty and weakness.

Over time, we find ourselves nodding at Michael’s insistence that his father is not the ‘“crazy machine-gunning mobster”’ that Kay (and the reader) had imagined, but someone with his own, even admirable ‘code of ethics’. The foundation is laid when we learn of Vito’s early career, as a kind of tenement Robin Hood, protecting the poor and vulnerable from vindictive landlords and thuggish hoods, piling up ‘good deeds as a banker piles up securities’. But there are other hints throughout. We learn that no one had ever seen the Don ‘in an uncontrollable rage’ or issuing a blind threat. He never hit his children. In a small but effective touch, we discover early on that he never formally adopted Tom Hagen, even though the Irishman grew up in the Corleone house, because, says Michael, ‘“my father said it would be disrespectful for Tom to change his name. Disrespectful to his own parents.”’

It’s this which helps make The Godfather such an unusual and accomplished novel. The reader comes to believe in a moral realm in which a Mafia boss who has taken many lives is simultaneously a highly moral man. That tension ensures The Godfather is much more than a page-turning blockbuster, though it has many of that genre’s virtues. It is a novel of unexpected nuance, a classic fable of twentieth-century America, of fathers and sons, of lust, riches and ambition, that will be read for as long as people are fascinated by family and power. Which is to say, forever.

___________________________________

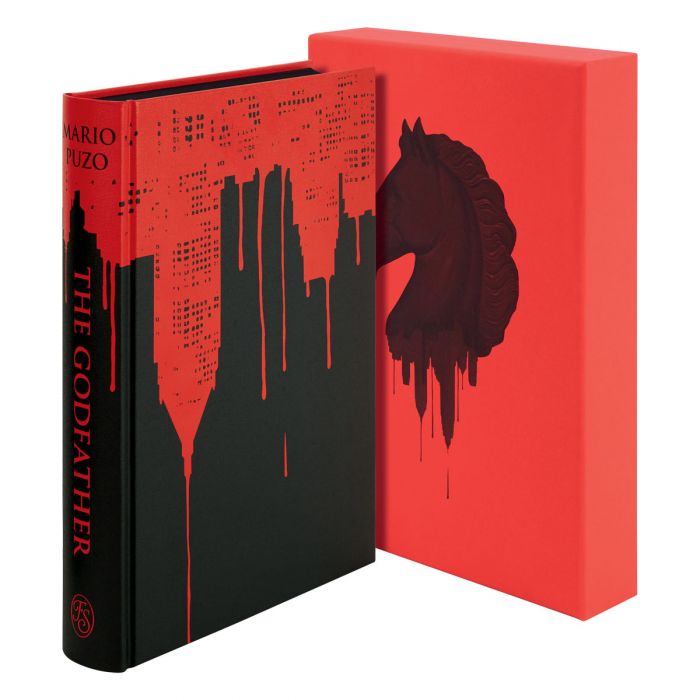

From Jonathan Freedland’s introduction to The Folio Society edition of Mario Puzo’s The Godfather illustrated by Robert Carter. Exclusively available from foliosociety.com/