Whether we like to admit it or not, we’re all fascinated by psychopaths. We always have been, even back when we didn’t have a name for them. Look at Iago, in Shakespeare’s Othello. I was an English literature student back in the ‘80s and I remember the acres of analysis once devoted to what Samuel Taylor Coleridge famously called Iago’s ‘motiveless malignancy’. 19th and early 20th-century critics just couldn’t get their heads round the fact that there was no rationale for his actions, no explanation that made any sense. He was purely and innately evil, ‘a being next to Devil’, as Coleridge puts it. None of the critics I read ever used the word psychopath to describe Iago, and the word itself wasn’t coined until 1885, long after Coleridge, but anyone reading or seeing the play now is left in no doubt.

In the context of this post, it’s interesting to note that Coleridge uses the phrase ‘motiveless malignancy’ when he’s discussing the (at best flimsy) reasons Iago himself gives for his behaviour. Coleridge doesn’t buy any of it and nor do we, but later psychopaths have been more articulate in this regard, and more adeptly self-serving. The gold standard here is clearly Patrick Bateman, in American Psycho, but we’ve also had Frederick Clegg, in John Fowles’ The Collector, Frank Cauldhame, in Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory, and TV’s Joe Goldberg (You) and Dexter Morgan, among many others.

Most of these characters are men (with a nod to exceptions like Amy Dunne in Gone Girl) and they tend to share many of the same traits – intelligence, self-deprecation, a certain world-weary knowingness, an ability to charm which dazzles the reader/viewer outside just as effectively it does their own hapless victims inside. And yes, they’re undoubtedly self-aware, or at least up to a point. But what about beyond that point: what about what really drives them? Do they feel remorse? How do they justify what they do? Do they see themselves as ‘beings next to Devil’, or (like another famous Shakespearean character) more sinned against than sinning?

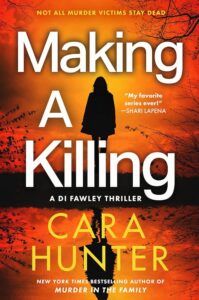

And why am I even asking these questions? Because the central protagonist in Making a Killing is a psychopath. Without giving too much away, one of the challenges I faced in writing the novel was to allow the reader inside the mind and motivations of that character, both past and present. And there was an additional technical issue (getting very writerly here!): the book already had a strong first-person narrator in the shape of my police officer, Adam Fawley, so his bête noire was going to need a vehicle that felt, sounded, and ideally looked completely different.

And that’s when I got lucky. And thank heavens for Instagram, too, because that’s where I came across an advert for The Shadow Work Journal, by Keila Shaheen. The book became a bestseller but there are (as I soon discovered) many other books and websites that offer something very similar, all based on the psychological theories of Carl Jung. Jung believed there is a ‘shadow’ in the psyche, which we either repress or deny, and it is only by confronting this dark side and reintegrating it into our Self that we can achieve a whole and healthy mind. ‘Shadow work’ is a structured approach designed to help people do exactly that.

And there it was – the answer I was looking for. What crime writer wouldn’t want their psychopath to psychoanalyse themselves, in full view of the reader?

So as the story progresses we have not only a standard third-person narrative, and Adam speaking in his own voice, we also have a parallel thread in which my character works their way through an online shadow-work app (faked up by me), confronting their demons, justifying their past decisions, and confessing their darkest thoughts and actions. We get the explanation Iago famously refused to give, saying at the end of the play ‘Demand me nothing: what you know, you know:/From this time forth I never will speak word.’ My character’s shadow-work app also promises silence and discretion, insisting that this is ‘a safe and private space for healing and self-empowerment’; no-one else will ever read it, no-one else will ever know. And in any case, they have it on a secure app, on a secret burner phone they never let out of their sight. What could possibly go wrong…

***