It has been a long copyright freeze—21 years to be exact—but the thaw is finally upon us. This year marks the single greatest arrival of works into the public domain since before the start of the digital age. Without getting too stuck in either the snow of copyright law or the winter storm metaphors, the essence is this: as of January 1, 2019, works published in the year of 1923 have now been freed from the shackles of copyright. They were due to be released into the public domain in 1999, but Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, aka the Sonny Bono Act, aka the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, which extended the copyright terms for another two decades (thanks Disney). But at long last, 2019 has arrived and the rights to hundreds of books, movies, and art have lifted, meaning all that was once under legal lock and key can now be read, watched, and re-imagined a little more freely. For crime fiction and classic mysteries, the implications are notable to say the least. 1923 was the dawn of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction—the heyday of Conan Doyle, Christie, and other favorites. To help you sort through the trove of newly public works (in the U.S.), we’ve highlighted a few standouts from the world of crime and mystery in 1923. In a way, they belonged to us already; now it’s legal.

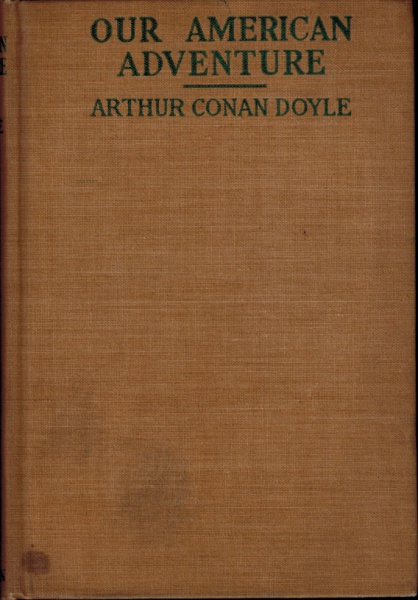

Our American Adventure by Arthur Conan Doyle

Toward the end of his life, Arthur Conan Doyle chronicled his journey to America and Canada, where he was giving lectures about spiritualism, in serialized publications in the UK’s Lloyd’s Sunday News. His North American observations during this evangelist time were later published in book form.

“The Real Story of a Bootlegger,” by Anonymous (early true crime sensation)

A waiter falls on hard times when prohibition is passed. This early account of true crime tells the tale of an “honest” bootlegger who supplied liquor to New York. “I have never run across a man in my life who refused to take a drink because it was against the law, and I have never met a man who thought I was a crook, just because I am a bootlegger and proud of it.”

Whose Body? (the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel), by Dorothy L. Sayers

A man wearing nothing but a pair of pince-nez is discovered dead in a bathtub. Iconic British gentleman detective Lord Peter Wimsey, new to criminal investigation as a pastime, begins investigating, noting (as the publisher made Sayers understate) that the dead man’s genitals reveal the suspect to be a goy since “the man in the bath is no more Sir Reuben Levy than Adolf Beck, poor devil, was John Smith.”

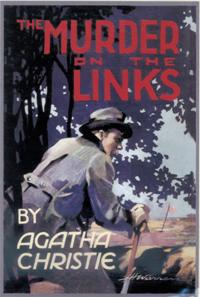

The Murder on the Links, by Agatha Christie

Poirot, whose tactics were approvingly compared to Sherlock Holmes in his earliest appearances, gets an urgent call summoning him to France. Upon arrival, he discovers two dead bodies face down on a golf course.

“The Chocolate Box,” “The Adventure of the Western Star,” “The Affair at the Victory Ball” short stories by Agatha Christie

In these Agatha Christie short stories, Poirot gets to the bottom of the provenance of a diamond jewel, investigates a framed drug overdose at a costumed ball, and tells of his failure to solve a crime back in Brussels.

Sherlock Holmes: Adventure of the Creeping Man, by Arthur Conan Doyle

Another short story, first published in The Strand in 1923, explores a scientific discovery, suggesting something more fantastical than Holmes’ usual criminal analysis. A renowned professor is engaged to marry a much younger woman, but a marked change in his behavior suggests something more troubling.

“The Oracle of the Dog” (Father Brown story) by G.K. Chesterton

Published first in the Pall Mall Magazine in December of 1923, this story follows amateur clerical detective Father Brown and a dog as they work in tandem to solve a murder case. It appears in The Incredulity of Father Brown, an eight-story collection that will enter public domain in 2020—stay tuned.