“I need protection from the enemy of rock and roll…” Lucinda Williams sings near the end of “Protection,” her soulful, blues-soaked protest song surveying American culture’s collapse into cruelty.

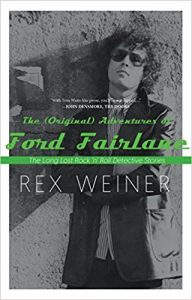

Rex Weiner created a character dedicated to protecting rock and roll, and serving the interests of justice, in 1979. Ford Fairlane, a private investigator whose clients populate the beleaguered punk rock music scene, first emerged with the aggression of a power chord in the pages of the now defunct magazine, “New York Rocker.” The lengthy, and then serialized, short story is now available, along with its sequel, in the nifty retrospective, The (Original) Adventures of Ford Fairlane.

His references to The Germs, CBGB, and Van Morrison’s lyrics might seem dated, but he arrives in the nick of time, considering that everything Fairlane was fighting—not only money-obsessed villains, but superficiality and corporate commercialism in the music industry—now reign supreme throughout American culture. If only Fairlane, and his hardboiled rock and roll ethos and attitude, could spend a few nights in contemporary New York or Los Angeles, America might return to a music scene that snapped with the excitement of rebellion, creativity, and free expression.

Weiner was a veteran of that very scene in New York, playing obscure blues covers in a band called “King Rude,” and the occasional rock original, with a title like, “I’m Pissed Off at You.” Writing in the Introduction to the recently published collection of Fairlane stories, Weiner admits that his band “couldn’t play for shit,” but that he was “intrigued” by what he observed in the loud and divey clubs. It was “a lifestyle,” he suggest, “a discordant rejection of the music industry, lots of heroin and too much alcohol, and more than a hint of violence in the air.” A juxtaposition with the pre-packaged sanitation of contemporary American culture, with gentrified city neighborhoods and bands with corporate sponsors, “New York was a dangerous place in those days.”

* * *

Acting on the inspiration of a punk sensibility that telegraphed and rejected the business cooptation of rock and roll, Weiner aspired to capture its magic with the written word. Having already written a journalistic account of Woodstock, he no longer had any interest in nonfiction, but instead hoped that he could create a literary hero, in the “classic film noir mode”—a “new wave detective” who chased down the secrets of the music industry, and rectified the injustices of young songwriters and raucous performers suffering under the corporate regime.

The first story, set in New York, has Fairlane on a scavenger hunt, at the behest of an unnamed British guitar hero, for a stolen Link Wray guitar. Moving through the music clubs, and interrogating German synthesizer players and voluptuous punk singers, soon has Fairlane dodging bullets and taking beatings. There is immense pleasure in the two Fairlane stories, each running around 50 pages, from not only the unique concept of the main character, but also Weiner’s mastery of the hardboiled vocabulary. The opening line of New York story is “The lights glimmered down Broadway like a strand of pearls slung over a black girl’s thigh.” As far as first impressions go, that is a pretty effective greeting, and Weiner’s subsequent descriptions, in the voice of Fairlane, have the ability to invigorate and amuse. Upon waking up from an unexpected assault, Fairlane says, “When I came to I was in a carnival and my head was the Ferris wheel.”

Fairlane is a less violent than most noir protagonists, and both stories demonstrate a refreshing vulnerability. He is not an untouchable superhero, and his own imperfections work in symbiosis with the values for which he struggles.

The New York investigation culminates with Fairlane uncovering and subverting a plot from the “Fourth Reich”—a neo-Nazi synthesizer band with wealthy benefactors—to destroy guitar-driven rock, and the organic artistry it represents – in favor of flawless, but soulless electronic music. The Fourth Reich not only steals all of the guitars that they can find, but they empty every the pawn shop and music store of string instruments. Fairlane, much to his horror and disgust, finds that the plan is working—all of the legendary New York clubs have booked synthesizer bands—and learns that the final solution of the musical Nazis is the broadcast of “Don’t Play Me”—a “perfect” computer song that will instantly hypnotize anyone who hears it.

Fairlane foils the fascist overthrow of music, but laments that the few rock critics who heard “Don’t Play Me,” are praising its technical mastery, and anticipating its follow up. The terminology might not have yet existed, but Weiner is prescient in his unhappy ending—a conclusion haunted by, in hindsight, the eventual dominance of digital beats, autotune, and the folding of various genres—from hip hop to country—into a repetitive hook, endlessly recycled in the perfection of a formula that guarantees monetary triumph, but also boredom, irrelevance, and frivolity.

* * *

In an interview with “Crime Spree,” Weiner asserted that the ultimate puzzle any great literary detective attempts to solve, whether it is Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, or his own Fairlane, is the “mystery of America.” Fairlane’s inquiry is seemingly how one strange civilization could unleash astounding creative energy in the morning, and then commit to killing it in the evening?

There is a rich irony in that Fairlane’s stories themselves became collateral damage in the American war of art against greed. In 1990, 20th Century Fox released the film adaptation of the Ford Fairlane character. Bringing Fairlane to the silver screen went through several phases over a period of ten years, undergoing steady dilution until fans were left with a mindless imitation of Rex Weiner’s sharp tales of crimes both personal and cultural. Weiner had little to do with the final product, the ultimate indictment of which is the “actor” who played Ford Fairlane—Andrew Dice Clay.

Clay had recently courted controversy and cash with his misogynistic comedic routine. Given that Clay’s idea of humor included vulgar versions of nursery rhymes, it isn’t surprising that his portrayal of Fairlane was little more than the imposition of his standup persona—cracking dumb lines with a delivery so corny that the entire movie becomes a test of the viewer’s ability to delay gagging and cringing.

Hollywood even failed at getting the soundtrack right. Instead of The Circle Jerks or Dead Kennedys, the music’s street cred comes from the likes of Motley Crue, Richie Sambora, and Dice Clay himself, torturing audiences with a rendition of “I Ain’t Got You,” a song originally made famous by The Blues Brothers.

Floyd Mutrux, the original screenwriter of the Fairlane movie, explains in an interview included the book that, like most parties involved with the stories and early adaptation plans, he could not bring himself to watch the eventual product, an especially bleak proposition considering that his plans were to cast Mel Gibson or Mickey Rourke in the role of a Fairlane who lives in a studio apartment in Los Angeles, and above all else, was “a real guy.”

The Ford Fairlane adventure that takes place in the LA of Rex Weiner’s invention was serialized in LA Weekly, and has the detective leading a search and rescue for an upcoming punk rock songstress. Two villains emerge during his investigation. The first is Mitch Mitchell, a manager whose specialty is “taking punk bands that are good and rough, smoothing the edges, rounding off the riffs, and turning them into mainstream pop bands that suck.” Even more hilariously, the other heel is the personal janitor to The Eagles.

To read how Fairlane succeeds in saving the life of a talented singer, and scoring a victory for the authentic spirit of rock and roll, is to experience memorable entertainment, but also to take an intoxicating, albeit melancholic, tour of a bygone America— the America when rock and roll’s lifeblood was the sweat left on the stage in an underground club, alternative weekly’s kept journalism eccentric, vibrant, and honest, and writers like Rex Weiner were identifying the real good guys, and their enemies.