What I told her was this: “Read Once Upon a River.”

Let me explain.

I was at an event promoting my own new novel, Once These Hills, when a woman approached me and asked me where I got the idea to write about my main character, a fierce mountain girl, good with a bow and arrow, who roams the hills of eastern Kentucky, killing game . . . and sometimes men. “The whole idea for it, the genesis of the entire book,” I answered, “comes from Bonnie Jo Campbell’s novel, Once Upon a River.”

I think she expected me to say more. I didn’t. Not because I intended to be rude, but because that was the whole of it. I simply said, “Read Once Upon a River.”

I could go on and talk about Campbell’s many awards and distinctions—they’re impressive—but for me, it’s more important that her book touched me so profoundly that I decided to write a novel in the same spirit—or to attempt to do so, at least. There’s such a deep sadness and beauty in Campbell’s tales of rural Michigan, such a terrible truth underneath. In reading her for the first time, I realized I was in the presence of a modern master.

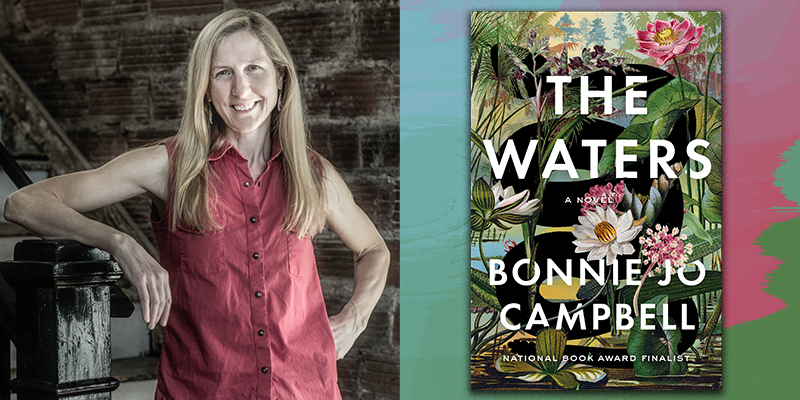

Her new novel, The Waters (2024, W.W. Norton) is again peopled with rural Michiganders: farmers, church people, and blue-collar workers. But Campbell adds something else this time, a mystical element that transforms the setting and its narrative, something that elevates the work to another level. Fans of American Salvage, Once Upon a River, Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, and Campbell’s other books will love this new novel. Yes, there are violent scenes, deviant passages, and the Campbellesque grit her fans all know and love.

So what about this new element, then?

The Waters definitely possesses something unearthly, something fierce, and at times something unsettling and eerie.

Anyway, I recently talked to her about all of this.

CM: Bonnie Jo, your excellent forthcoming novel, The Waters (W.W. Norton, 2024) signals a stylistic departure from your story collections, American Salvage and Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, and from your previous novel, Once Upon a River. The Waters is chock full of rural types familiar to most readers, like those we see in your previous work, but it also establishes a sort of mythology around characters, around a core group of women and around their simultaneous power and vulnerability. In this sense it veers into mythology, into a sort of magical realism (?) we don’t see in your other work. The Waters is a fantastic synthesis of real and unreal, or real and surreal, or whatever we’re calling it. Did you set out to write a novel like this? Did the style emerge organically?

CM: Bonnie Jo, your excellent forthcoming novel, The Waters (W.W. Norton, 2024) signals a stylistic departure from your story collections, American Salvage and Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, and from your previous novel, Once Upon a River. The Waters is chock full of rural types familiar to most readers, like those we see in your previous work, but it also establishes a sort of mythology around characters, around a core group of women and around their simultaneous power and vulnerability. In this sense it veers into mythology, into a sort of magical realism (?) we don’t see in your other work. The Waters is a fantastic synthesis of real and unreal, or real and surreal, or whatever we’re calling it. Did you set out to write a novel like this? Did the style emerge organically?

BJC: Thank you, Chris—I am thrilled that you like The Waters. You wouldn’t believe what I set out to write many moons ago: a playful romp about a teenager who loves mathematics and lives on a farm with an annoying little sister, a boozy mother, and a bitter, angry grandmother. But as I wrote that book, called Math Slut, I became haunted by the tragedy and struggle that I sensed lay behind the comedy. So I went back in time to when my protagonist, nicknamed Donkey, was eleven, and I discovered the strangeness and mystery of all the characters and especially the strangeness and mystery of the swamp itself. Swamps are bubbling cauldrons of fertility and obfuscation and a great place for trouble. As I allowed myself to depart from strict realism to embrace a more gothic sensibility, I found even my sentence structure becoming more sinewy and complex. This allowed the whole sensibility of the book to become shimmery.

CM: It’s not a spoiler to say that the novel depicts more than one violation of female characters–rape, assault, gun violence. Some of these events affect not only the characters but the narrative arc itself. Perhaps they even shape a collective consciousness amongst other characters. These are formative events in the world of the town, “sins” that govern behavior and the broader mindset of the characters . . . even if not everyone is aware of the specific transgressions. What was your objective in conceiving of crime in this respect?

BJC: Like the characters in the book, I only gradually came to know the nature of the crimes and transgressions. The difference is that many in the town are willfully ignorant, blinded by their worshipful view of certain powerful men. Even their love of firearms—also connected to a problematic view of masculinity—blinds them to the dangerous situations they create and perpetuate. Meanwhile, the most violent men in the story see the nonconforming behavior of the women on the island as sinful. In my way of seeing, nobody is innocent, but it seems those who are self-righteousness are likely to commit the worst crimes. Also, there is the natural world. Though we can’t classify the natural world as criminal, there are inherent, essential dangers there as well, and those dangers also drive the story.

CM: The Waters establishes some dichotomies, conflicts that run the course of the novel. One of them involves natural healing versus conventional Western medicine. A central character is Hermine “Herself” Zook, a healer who has inherited her skills from an ancestor, or from many ancestors, perhaps ancient ones. Her work is the province of women exclusively, and it’s shrouded in some mystery. Interestingly, the rural people of the novel put great stock in Herself’s elixirs and healing herbs. And yet, they are kept at bay from her work. In fact, they are prohibited from the swamp island on which she lives. What is it that you wanted to explore with this dichotomy, or with healing and women’s relationship to it?

BJC: Well, I really love writing a cranky old woman, an embittered farm wife, or any woman who has had to grow hard as a result of hard living. Such women can be—or seem to be—far more brutal than the men, and they’ve endured childbirth to boot! As a writer, it’s a real pleasure to express anger and bitterness through a character like Hermine who can skin a rattlesnake as easily as she can make a blueberry pie. And then there’s an additional pleasure when the plot allows us to glimpse the soft-hearted side of such characters—after all, she loves her granddaughter powerfully and would do anything for her. Personally, as I have moved through cancer and other maladies of aging, I have come to feel ambivalent about our medical model, where every remedy involves pills or knives (or occasionally radiation). Western Medicine is great if you break a bone and it’s almost certainly the best thing if you have cancer, but a whole lot of minor medical complaints would be better served by a cup of herbal tea, or even a well-administered placebo. And I do believe that a lot of what ails us—aches, pains, even some diseases—is really soul trouble, the trouble of being human in this world, and for that a swamp-witch might know more than doctor.

“It’s a real pleasure to express anger and bitterness through a character like Hermine who can skin a rattlesnake as easily as she can make a blueberry pie.” –Bonnie Jo Campbell

CM: It seems that some of the women characters in the novel are unwillingly destined to play roles, or to serve some non-traditional function. This not to say that they do not “take to” their vocations, their charge, and even thrive there. But they may not always want to serve in the capacity chosen for them. I’m thinking of a character like Dorothy, known as “Donkey.” In some respects, this young girl wants to go to school, wants to study mathematics, wants to have a normal family. But work as a healer, and as Hermine’s protégé, is thrust upon her. Can you talk about this dynamic and about the character of Dorothy? What does she represent in the world of the novel?

BJC: In the mythology of this family, as in most fairy tales, the youngest person turns out to be the wisest. I’m usually uneasy putting a kid’s point of view out front—I’m not interested in exploring innocence—but I’m interested in how her ability to be logical works as a superpower; like any superpower, she has to learn to use it judiciously. In middle class families, kids supposedly get to be carefree, but in poor families, kids have jobs to do, and in this case, she has to help her granny cure what ails the town—not doing so would put them all in danger. And of course, every kid’s side job is also to rebel against her family. Donkey’s been told her whole life that a father doesn’t matter, so she’s seeking a father in every man in town; her mother says school is a racket, and so Donkey hungers for a formal education. The rattlesnake is the one animal she is forbidden to screw around with, so naturally, that is the animal she’s obsessed with, and that ends about as well as you might expect.

CM: Can you talk about the importance of physical landscape in your work, both in The Waters and in your previous books. Flora and fauna, water, the woods, even cultivated farmland, have certain valences in your work. They change depending on the narrative and on which characters inhabit these areas. Yes, this question is intentionally broad, and there would be no way to answer in short form. Even so, can you explain what it is about physical nature that compels you to write about it as you do, so lyrically and meaningfully?

BJC: Oh, swamp, I sing your praises! The landscape gives birth to everything else in this story, and in all my work really. My first novel, Q Road, is a dry-land novel about a girl who marries a farmer in order to own his property; my second novel, Once Upon a River, is about a girl who is the physical embodiment of a Michigan river. This novel, The Waters, is the swamp, through and through, with all the stink and lushness and fertility and uncertainty—the very ground is unstable and might swallow up a hapless wanderer. The landscape—with its beauty and dangers—works as tonic on some characters, and we get to know everybody in the book by how they see and respond to this place. Some want to preserve the swamp and all that grows here; others want to fill it in, develop it, and civilize and Christianize it; a few would like to hide away here and not be found. Choosing the right landscape for any story is critical because it will determine what kind of story it is. During the writing of The Waters, I kept studying the swamp, let it bloom in my mind and in the natural world around me. I read books about swamps, fens, and bogs, and I spent time wandering through natural landscapes, trying to figure out what happens next. I can honestly say that the swamp itself helped me write this book. Helped a lot.