You don’t notice her at first, but when you do, she’s peering over the garden hedge or through the lace curtains of a tea shop. She’s just another nosy old lady, absent-minded and a gossip, in hats and gloves when she goes out into the village, clutching her purse to her chest, ready to pester the police with a vaguely crackpot question or warning. When you think of the spinster sleuths of the Golden Age, who comes to mind? Christie’s Jane Marple, of course, followed by Patricia Wentworth’s Maud Silver, a retired governess turned private detective, and Dorothy Sayers’s Miss Climpson, who runs an employment agency funded by Lord Peter Wimsey as a cover for a crew of women secretaries cum investigators.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, when Anna Katherine Green introduced Miss Amelia Butterworth of Grammercy Park in That Affair Next Door with the inimitable phrase, “I am not an inquisitive woman,” spinster sleuths have played a significant role in mystery fiction. The spinster and her widowed sisters of text and film, Gladys Mitchell’s Mrs. Bradley and Jessica Fletcher in Murder, She Wrote, were usually north of sixty-five; her wrinkles, glasses, and white hair made her invisible (she was invariably white, which helped place her socially as a harmless old biddy). Her invisibility, in fact, enhanced her powers of observation and psychological astuteness. In Murder in the Vicarage Christie has Miss Marple modestly boast, “There is no detective in England equal to a spinster lady of uncertain age with plenty of time of her hands.”

Although she was straight, her status as an elderly female in society was ambiguous and her friendships usually female. In the 1970s she was often replaced by a private eye or cop, still unmarried but sexually adventurous and usually young. Miss Marple tottering around St. Mary Mead became Cordelia Gray who had an unsuitable job for a woman. Miss Amelie Butterworth, hesitant to walk down a New York alley without an escort, was transformed into V.I. Warshawski, prowling the mean streets of Chicago. Out with the knitting and in with the bolt cutters and skeleton keys. Even if the modern detective was an amateur, she often had ties to the world of the police and the courts, often through a father or boyfriend.

How did the lesbian sleuth who appeared in the 1980s fit into this new model? Like her straight sisters, she was young, she was fit, and she had an active erotic life. Unless she was an amateur, she carried a handgun, and she sometimes drank too much. In theory she was a spinster, since queer people couldn’t legally marry, though she often had erotic entanglements and sometimes long-term relationships with women. (Sandra Scoppetone’s New York PI Lauren Laurano was one of few lesbian detectives to have a happy partnership). In other ways she rarely fit the model of spinster sleuth developed by Agatha Christie and Patricia Wentworth: “a little old lady who nobody noticed, but who noticed everything.” Detectives such as Mickey Knight in New Orleans, Jane Lawless in Minneapolis, Kate Delafield in Los Angeles, and Emma Victor in San Francisco, to name some of the more prominent sleuths, private eyes, and cops, were actively involved in their queer communities. Although many of the cases they investigated involved the usual suspects (horrible men who wreaked mayhem on women and children), these sleuths brought a distinctly LGBTQ sensibility to their detecting work, tinged with feminist idealism and gay pride. Black lesbian mystery writer Penny Micklebury made her Washington D.C. detective, Lt. Gianna Maglione, head of the Hate Crimes Unit; her partner in crime-solving is Mimi Patterson, an African-American reporter. Nikki Baker’s Virginia Kelly was another Black lesbian sleuth, a businesswoman. Baker, who debuted in 1991, was one of the first to explore the intersectionality of race and gender in an entertaining mystery.

What lesbian detectives had in common with heterosexual women detectives in the many mystery series that proliferated from the 1980s onward, were that they rarely aged. Gay or straight, most of them started out in their thirties, perhaps crept into their early forties, and then stayed there, year after year, still jumping out of buildings, running down urban streets, and flirting in their spare time with available romantic partners, also no older than forty-five.

To some degree, this convention has to do with the reality of a detective’s life and work; some things you just can’t do as well when you’ve had joint replacements. The choice may also have to do with readership. Above a certain age, a woman can’t use her sexy voice or other feminine wiles to interest and entrap a suspect; it’s too creepy. Readership issues have influenced the lesbian writer as well. At a time when YA literature about queer adolescents proliferates and when the lesbian romance and/or erotica genre usually features younger women, a lesbian mystery writer might well hesitate to age her series detective or to create a sleuth older than fifty. In the popular imagination, lesbians are most acceptable when they’re young and attractive.

What’s often missing in contemporary lesbian genre writing are nuanced portraits of mature queer women, women who are powerful and wise, but also physically weaker and sometimes relatively poor after a lifetime of lesser wages or jobs in the nonprofit world. One well-known lesbian mystery writer who did take the radical step of allowing her series character to age is Katherine V. Forrest. Forrest’s series about the LAPD homicide detective Kate Delafield began in 1984 with Amateur City when Kate was in her thirties. Kate is and remains something of a spinster though she has loved deeply and at times lived with a lover. Her relationship in the later books with paralegal Aimee Grant is rarely smooth, in part due to Kate’s struggles with the emotional demands of her job and her reliance on the bottle to dull the pain. In Hancock Park (2004) she seems to be in her fifties, while in High Desert (2013), set in 2008, she’s over sixty. She’s recently retired, but retirement isn’t good for her. Instead, accumulated trauma from all she’s seen in her line of work is making life unbearable. Once again, she’s alone, Aimee having left her because of her alcoholism. Her trauma isn’t glossed over in High Desert, but explored sensitively as a form of unbearable PTSD, and her efforts at recovery aren’t minimized either, as Kate takes on one last case and acknowledges both her own strengths and her vulnerabilities.

Just as interesting as Kate’s own age in High Desert are the ages of women around her, some of them elders she’s known for years. Forrest avoids the stereotypes of old women as either pathetic or befuddled. Feisty they may be, but rarely unreasonably belligerent. Lesbians or not, they’re women at the end of long, richly complex lives, who still have their wits about them, if not their physical strength. One friend in particular has been in Kate’s life since the second novel, Murder at the Nightwood Bar. By aging the characters, Forrest is able to convey the sweetness and pain of years-long connection and the loss that follows a death.

Katherine Forrest’s decision to allow Kate Delafield to grow older means that Kate can look back on her life and think about her past loves, community, and working life. It allows her long-time lesbian character to feel and express what it means to be female and queer in a society that’s rapidly changing to accommodate longer lives and celebrate role models like Nancy Pelosi, Maxine Waters, and Lily Tomlin, all in their eighties. At the close of High Desert, Kate is finally coming to terms with her self-destructive habits and modeling for the reader new possibilities for the last decades of life. Her creator Katherine Forrest is soon to publish her tenth and what she says is her final mystery in the series, The Delafield Agency, which will again tackle issues of aging.

*

Printer Pam Nilsen was my age, in her early thirties, when she appeared in my first mystery, Murder in the Collective (1984), and she stayed that age for five years, through two more mysteries. When I introduced my second amateur detective, vagabond translator Cassandra Reilly, in a short story in 1988, I intentionally made her about six years older than me; she remained there as I lapped her. By The Case of the Orphaned Bassoonists (2000), she was still in her mid-forties, though mortality seemed to be an increasing preoccupation. She was played in the film Gaudi Afternoon by Judy Davis who was herself forty-five in 2000 when it was shot in Barcelona.

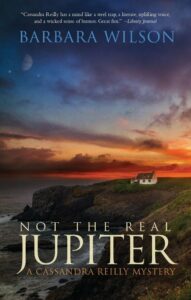

Twenty years ago I went on hiatus from crime writing, while I turned to translation and nonfiction, essays, travel writing, and more academic books published by university presses about Scandinavia and the indigenous Sámi people. But I never quite forgot about Cassandra Reilly, and one day a couple of years ago, wanting to write something more fun and without endnotes, I started up with her again. In the first book of this revived series, Not the Real Jupiter, Cassandra is around seventy, like me. Aging and her work as a freelance translator are part of the story.

Cassandra isn’t a traditional detective; the novels and short stories about her have always been as much about travel and place, translation and the publishing world as they are about crime. Her profession as a literary translator, from Spanish to English, gives her a reason to investigate some crimes set in other countries as well as in England, where she’s based. Her cohort is varied, but many of her friends are getting older too.

In many ways Cassandra is a paragon of the spinster sleuth. She is resolutely single, though not without a sex life. Translation is often invisible work, but it allows her to move, respectably unnoticed, through a variety of social situations. Jane Marple was an influence on my choice to focus on Cassandra as an older sleuth; so was Hilary Tamar, the aging, non-binary legal scholar of Sarah Caudwell’s too brief series, who pieces together complex puzzles hardly leaving her Oxford study. Mrs. Pollifax, the accidental, older spy created by Dorothy Gilman, was always another favorite of mine for her sangfroid in the midst of danger. She is as unflappable as Cassandra, in her best moments.

What I noticed as I was writing Not the Real Jupiter and my current project about Cassandra is that by making my detective older, I’m able to deal with a broad palette of memory and experience, as well as LGBTQ social life, the economics of aging, and the long tentacles of the past. In her late sixties, Cassandra still is part of the working world and yet highly conscious that many around her are retiring or changing occupations. She may stay her current age for a while, or I may explore some of her earlier cases as memories. My biggest dilemma these days is not her age, but the fact that she was created to be a constant traveler. How will that work with COVID’s lockdowns and restrictions? For now she remains precariously perched in the before-times of 2019, as I myself get older in a pandemic world.

*

In 1991, Paulina Palmer wrote an essay on lesbian thrillers for What Lesbians Do in Books, the first British anthology of critical writing about lesbians as writers and readers. The thrillers weren’t so many then: Paulina Palmer discussed my work, and that of Katherine Forrest, Mary Wings, Sarah Dreher, and Rebecca O’Rourke in terms of characters, settings, and how we dealt with race, class, and the patriarchy. Looking at this essay thirty years later I’m struck by the issues Palmer raised at the end:

The majority of lesbian thriller writers, while making some attempt to challenge racist stereotypes, make little or no effort to challenge prejudices relating to age. The fashionable age for the lesbian investigator in the selection of novels discussed in this essay is around 30. . . The propensity of writers of the lesbian detective novel and crime novel to erase or marginalise older and elderly women from their novels is, in actual fact, surprising. . .perhaps future writers will start to address the topic of age. I look forward to seeing what they produce.

For now, a variety of the series characters that first appeared in the 1980s and early 1990s aren’t aging very quickly despite all that has happened in their lives. Likewise, most contemporary lesbian crime writers have followed the path of creating protagonists in their thirties and forties who are athletic, gun-toting, and interested in sex but bad at relationships. Straight women writers do this as well: Sara Paretsky’s enduring feminist hero, V.I. Warshawski, is still mixing it up physically with the bad guys, even though by rights her bruises and broken bones should be taking longer to mend after all these years.

It makes abundant sense within the world of a series to keep a PI jogging in place. But perhaps there’s also a place for the queer old spinster sleuth, a lesbian character who can challenge stereotypes of older women, and who can reflect on aging and on memories of her LGBTQ community, who can continue to grow and to change, even as she uses her still active brain to solve the puzzles so beloved of the mystery reader.

***