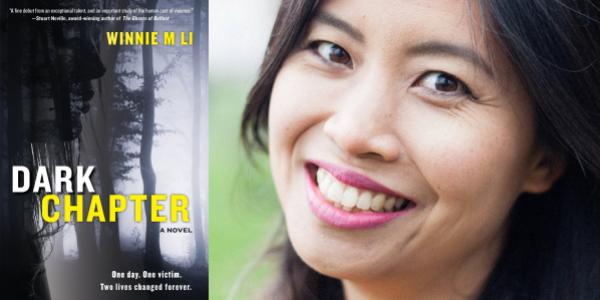

The haunting experience of reading Winnie M. Li’s debut Dark Chapter derives in large part from the knowledge that the author’s real-life rape provided the inspiration for this work of fiction. “They say events like this change your life forever,” Li writes, preparing us for the story that unfolds: a woman walking through a park in Belfast comes across a stranger who asks for directions. Against her wishes, he continues to follow her, finally ambushing her on a deserted hiking trail. We can guess what happens next. But unlike many of the crime procedurals we’re accustomed to watching on television, the scene does not cut away.

While the incident itself may be relatively straightforward, the individuals and the circumstances that lead them to this moment prove more complicated to parse out, particularly for the Irish news media covering the attack. The novel intertwines the two narratives of both rape victim and rapist: in this case, they are 29-year-old Vivian, a Taiwanese-American professional living in London, and 15-year-old Johnny, an Irish Traveller temporarily residing in a community of trailer-vans near the woods. Li illuminates the full scope of her characters’ lives: their families, upbringing, past experiences that inform their decision-making, and how their identities have shaped who they are. Her commitment to humanizing them makes for rich storytelling that goes beyond surface-level stereotypes about sexual assault.

In an era when women and men choosing to break their silence have ignited a movement, Li delivers her own contribution in the form of a crime novel that centers the survivor’s point of view. Ultimately, her work challenges not only genre conventions but also the broader conversations about rape and rape culture.

Mimi Wong: You wrote in an essay that film and TV influenced your approach to this story. In the prologue, Vivian recalls the memory as if she’s watching a movie: “I have replayed it enough times already. If I could just freeze it there—in that final moment, perched between the sunlit pasture and the plunging abyss—then everything would be fine.” Was the use of cinematic language something you deliberately wanted to play with when telling Vivian’s story, or did it come about organically?

Winnie M. Li: It wasn’t deliberate. You’re probably the first person to point that out in terms of [it being] down to the word level. It just came out organically. Maybe that’s how I think and write since I used to work in film. I mention in that essay, I think on a broader level that’s how we as 20th-century human beings think about memory and story because we’ve all grown up watching television. Movies are our go-to way of envisioning things. Right now, if you want to see a news story, you don’t read an article. You just watch a video that CNN’s put together. So visual storytelling has taken over in terms of how we perceive the world and how we think of memory.

Mimi Wong: So much of how we understand sexual assault and rape is through movies. It’s through watching Law & Order. That’s the first place our mind tends to wander. Is that also where you found your head space at?

Winnie M. Li: It would be interesting to ask anyone from 400 years ago how they perceived rape and sexual assault. But one of the reasons I do the work I do on this issue is that all the impressions and perceptions we have about rape and sexual assault do come from the media because it’s not often a topic that people speak about from firsthand experience openly. It’s either news stories or episodes of Law & Order, Cape Fear, or Game of Thrones. And that’s the problem because a lot of times that’s not being written by survivors. It’s not being written by people with a lived experience and with an understanding of the reality of it. It’s written by men, who maybe put a rape scene in there to sensationalize things. Or [they] put a rape scene in there to show that she’s a strong woman who has demons in her past. That’s really problematic. I think that’s what prompted me in my own coming to terms with my own trauma—just the realization that what I had lived through was so different from I had expected this to be like.

I wrote it because I wanted to do justice to the survivor’s experience in its totality as much as I could in a single book, and also show that the survivor is capable of telling the story herself.Often times we never see things from the perspective of the survivor. So that’s why the book needed to be written from the survivor’s perspective. Basically, I wrote it because I wanted to do justice to the survivor’s experience in its totality as much as I could in a single book, and also show that the survivor is capable of telling the story herself. There’s a subjectivity that is valuable, which is [Vivian’s] subjectivity. And I also wanted to intertwine that with the perpetrator’s because that’s where the story really starts, is with the person who [commits] the crime.

Mimi Wong: What was the experience of exploring both sides like for you?

Winnie M. Li: I don’t think I ever wanted to write a book where it was just Vivian. There are already a lot of books out there that are good memoirs like After Silence by Nancy Venable Raine and Lucky by Alice Sebold. There’s a really good book called I Will Find You by Joanna Connors, which came out two years ago. There are some really good rape memoirs out there, which are very much about the survivor’s experience and her aftermath of the path toward recovery. I didn’t really want to write something that was in that vein.

Writing the book from Johnny’s perspective was an extension of me coming to terms with what had happened and trying to make sense of it. The only way I could make sense of it was to try and make sense of his character. I admit that a) I’m not trying to represent the real-life individual, but then b) it’s a complete active imagination to try and imagine what his life was like. I think that act of seeing another person as a human being is probably something that we should do more in our lives anyway because there’s a tendency to only think about people who come from our side of the tracks, or our world, as being other human beings. But it is important to imagine what the life of a totally different person would be like. That was the more interesting, creative thrust to the novel was imagining his life.

Mimi Wong: You’ve said that you also had to do some research into the Irish Travellers’ society that Johnny comes from, which is not necessarily well known, especially to American readers.

Winnie M. Li: Yeah, it’s a quite closed off society. It’s not a society you can infiltrate. There’s a Travellers’ rights organization in London, Dublin, and Belfast. So I met with them and had different conversations with them. And then I went to a few horse fairs in London, in the UK, where Travellers get together. They’re called horse fairs (traditionally, that’s when they traded horses), but it’s more like a gathering of different Traveller families. Now it also attracts tourists, so there’s this whole weird sense of the Other.

In some ways, I was trying to imagine what it was like to be in that marginalized group and be very aware of the fact that other people view [them] in this way. Travellers are very aware of the fact that they’re outside of mainstream society. And they’re quite proud of their heritage. But there’s always a sense that the rest of society doesn’t understand [them]. For me, to understand that mentality was the key to unlocking Johnny’s character. Frankly, if he wasn’t from that marginalized group, I might not have written the story.

Mimi Wong: In the novel, you do this work of negotiating between two characters who are marginalized in different ways. Vivian is a woman of color. As an Asian American woman abroad, she deals with different kinds of microaggressions and racism. Meanwhile, Johnny comes from a poor family. He’s abused. He lacks education. You seem very careful to show that discrepancy between the two of them.

Winnie M. Li: Even though Vivian is a woman of color and her parents are immigrants, she has much more privilege than Johnny. She was raised with a big emphasis on education, and she goes to Harvard, and there’s so much privilege that comes with that. They are rape victim and rapist, but the characters themselves are maybe slightly different from your stereotypical image of what a rape victim looks like, what a rapist looks like. That comes from reality. There are always going to be pairings of victim and perpetrator that fall into different socioeconomic and demographic groups. I think it’s important to see how an individual’s sense of identity and journey through life is impacted by things like race, class, and education, but then how that suddenly gets challenged when an act of violence like this occurs.

Mimi Wong: I read the novel not just as a #MeToo story but as an Asian American #MeToo story. I feel like Vivian’s awareness of her otherness, of her race, as she’s traveling is so relatable. And I was noticing how, as Vivian is moving through these spaces, she’s constantly aware of how she’s being perceived. Even to the degree that after her rape, she can’t just be a rape victim. When she goes to the hospital and requests that her friend accompanies her, the receptionist asks if it’s because she needs a translator. Even in that moment, she can’t just exist without being reminded of her race.

Winnie M. Li: I’m glad you were able to relate because I think it’s something that people don’t really think about. Certainly, you don’t see that experience that much in books or literature. Most of the books published by Asian American writers tend to be about identity within the immigrant experience. But there’s not that many things I’ve read that capture the experience of being Asian American traveling in Europe. If I go hiking in the Scottish Highlands, I’m probably the only person of color on the trail. And it doesn’t really occur to me. That’s the thing about being a minority of any form, I suppose. I don’t go through every moment of my life thinking, “I’m Asian, I’m Asian, I’m Asian.” I am who I am. For any of us, that’s our subjectivity as its purest. This is how we perceive the world.

But then as you grow older, you become aware of the fact that the world perceives you differently because of how you look, and that’s not something that you have that much control over. And you have some control over it maybe by being able to speak English well or having a personality that counters stereotypes of what an Asian woman’s personality is supposed to be like. But at the end of the day, I can’t get a race change, so I can’t change how people perceive me in any given situation. But it’s something you’re constantly aware of, and it’s an additional thing you have to negotiate when you’re abroad.

I certainly know that if I had been a man and had gone on that hike, I wouldn’t have been raped by that person that day. If I was a woman that wasn’t a woman of color, I don’t know. I probably could have been raped. And this is why I tried to see it from Johnny’s perspective. Did the very fact that I stood out as being something “exotic” cause him to pursue that line of behavior? I’m never going to be able to answer that in real life. Certainly, when I try to imagine it from Johnny’s perspective, Vivian being foreign or Other is the first thing he sees right away.

Mimi Wong: The #MeToo movement was started by Tarana Burke in 2006, but it was really only in October 2017 that it went viral and became part of our mainstream conversation. Your novel came out right before that. How do you see the relationship between your novel and that movement?

Winnie M. Li: Obviously, I wrote the book before the #MeToo movement became a really significant thing. I actually didn’t know about #MeToo until October 2017. But there were other hashtags like #BeenRapedNeverReported. And running throughout the book there was this commentary on the media, the way these stories are perceived and the way that we ourselves—whether we’re survivors or not—have with media portrayals of this topic. So that whole section after the rape—where Vivian is reading the news headlines about her rape, and even the end when she does the radio interview—her whole experience is very much intertwined with media portrayals of it.

Two days after my assault, like Vivian, I was googling and found all these media headlines, and I was listening to a radio chat show about my rape. And it was just really weird to hear that.It was the same with me. My own experience from the very beginning was very mediated. I was very conscious of the fact that people were writing about it and talking about it in the media. Two days after my assault, like Vivian, I was googling and found all these media headlines, and I was listening to a radio chat show about my rape. And it was just really weird to hear that. There are all these complete strangers talking about my rape and using it as a talking point about “Is Belfast a safe city?” It was kind of insulting. I did hear this woman say: “This woman’s life is ruined. This wee Chinese girl’s life is ruined.” There are all these people talking about something very personal that happened to me. It made me realize that all these people feel like they can say something, but where is the space for my own voice as the victim of that crime? If anyone has the right to share that story, that’s me because I was the person that was the victim. I have the best perspective in all of this.

In spring 2014, the Huffington Post ran a number of articles for Sexual Assault Awareness Month. I basically outed myself as a survivor. I put that on Facebook, and then a lot of people that I knew on Facebook were like, “I didn’t know.” So it was this gradual coming out process on social media for me. And that was prompted by seeing other people’s stories on social media and starting to realize that other people are sharing their stories online. This is an unprecedented platform, which we didn’t have 10 or 15 years ago. So I think my own coming out process and journey toward writing Dark Chapter are very much informed by those kinds of conversations that are happening on social media.

Mimi Wong: Do you feel like your novel is being read or received a little differently now—now that we have this knowledge and acceptable way of talking about rape and sexual assault?

Winnie M. Li: I think so. I think on an industry perspective, publishers might have been scared to publish something [like Dark Chapter]. I got comments where publishers said, “It’s very brutal and unflinching in its portrayal of sexual assault, and it might be too much for our readers.” But now publishers realize that the public is hungry for it. But I’ve always known that the public is hungry, and I’ve always known that there are people out there who want to share their experiences. Ultimately, I think art is an important way to share these experiences and maybe for people to reach a different understanding about something that isn’t spoken about so openly.