Sherlock Holmes is the most famous fictional detective ever created. The supremely rational sleuth and his dependable companion, Dr Watson, will forever be associated with the gaslit streets of late nineteenth and early twentieth century London. Yet Holmes and Watson were not the only ones solving mysterious crimes and foiling the plans of villainous masterminds in the popular literature of the period. Sherlock had dozens and dozens of rivals. A few are still read today. Some of them have been justly forgotten. Many others deserve rescuing from near oblivion.

Sherlock Holmes became so startlingly popular that writers looking to create rival detectives faced an immediate difficulty. How could they differentiate their creations from Holmes? Some didn’t really bother. Many Holmes clones can be found lurking among the back numbers of late Victorian and Edwardian periodicals. Some openly advertised their resemblance to the great detective. Some were rapidly categorized as Holmes lookalikes at the time they were first published. Sexton Blake, for instance, the creation of a prolific writer of stories for boys’ papers named Harry Blyth, was soon dubbed “the office boys’ Sherlock Holmes.”

Other writers chose a different strategy. Instead of trying to make their characters even stranger and more intellectual than Holmes, they chose to emphasize their ordinariness. By far the most common technique writers used in competing with Holmes, however, and one that is still employed today, was to give their characters a Unique Selling Point which was emphasized in every story. Provide your detective with a particular characteristic or give him or her the kind of career and lifestyle that no other detective had and (you hoped) you were several steps on the path towards success.

The rivals of Sherlock Holmes therefore ranged from blind detectives to gypsy detectives, from Canadian woodsmen to wise old Hindus, and from unassuming priests to proto-feminists. Here are eight of my favorites:

Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen

Could there be a more cerebral detective than the great Sherlock Holmes? One more committed to the power of cold, unemotional reasoning to solve crimes? Step forward the magnificently named Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, otherwise known as “The Thinking Machine.” Van Dusen was the creation of Jacques Futrelle, an American writer. In 1912, Futrelle had been visiting England and booked passage on a liner back to New York. Unfortunately, it was the Titanic. When ship met iceberg, he was amongst nearly 1500 who drowned. However, his detective—arrogant, cantankerous and eccentric—lives on, solving apparently insoluble mysteries in dozens of short stories.

Carnacki the Ghost Finder

A house is haunted by a ghostly horse. An ancient dagger takes on a life of its own and attempts murder. A giant human hand appears in a room where, many years ago, a grisly killing took place. These are just some of the mysteries investigated by Carnacki the Ghost Finder. The Edwardian era was a golden age for the kind of supernatural Sherlocks who looked into crimes that were not necessarily of this earth. The greatest of these occult detectives and the most obviously Sherlockian was Thomas Carnacki who appeared in a series of short stories by William Hope Hodgson, author of pioneering horror novels such as The House on the Borderland and The Ghost Pirates.

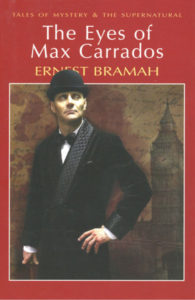

Max Carrados

A blind man might seem to be at a significant disadvantage as a detective but not one whose other senses are as preternaturally acute as those of Ernest Bramah’s Max Carrados. Some of Carrados’s abilities verge on the supernatural. He can read fine print by touch alone and shoot accurately at targets he cannot see but, in other ways, he is a sympathetic and down-to-earth character. The Carrados stories, the first of which were published in 1914, are all well written and remain worth reading. Bramah was a popular writer in his day. His 1907 science fiction novel, What Might Have Been, a work of alternate history, was later reviewed by George Orwell and some critics have claimed it as an influence on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Lady Molly of Scotland Yard

Nearly a decade before women in real life were able to join the Metropolitan Police in London, Baroness Emma Orczy had created a brilliant fictional policewoman in Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. As narrated by her adoring sidekick, Mary Granard, Lady Molly’s adventures are very much of their time but are still great fun to read. Baroness Orczy’s most famous character is the Scarlet Pimpernel, the daring and mysterious savior of French aristocrats from the revolutionary guillotine. She also created two memorable detectives in Lady Molly and, in another series of short stories, “The Old Man in the Corner” who solves baffling crimes whilst barely stirring from his seat in a London teashop.

Madelyn Mack

In 1914, a writer named Hugh Cosgo Weir introduced a fascinating female Sherlock in Madelyn Mack, a young American woman with a genius for criminology. Like Holmes, Madelyn attracts much admiring attention for her startling deductive abilities. Also like Holmes she has her own Watson (in the journalist Nora Noraker) and her own eccentricities – she carries a locket around her neck in which she stores cola berries to keep her awake for days at a stretch when she is on a particularly demanding case. Weir worked for a time in the film industry and, thanks to his contacts in Hollywood, several of the Madelyn Mack stories were made into short films starring Alice Joyce, a popular actress who appeared in more than 200 movies in the silent era.

Martin Hewitt

Of all the rivals of Sherlock Holmes who sprang up in the years immediately following Conan Doyle’s startling success with his detective, the most consistently admired was Arthur Morrison’s Martin Hewitt. Like Holmes, Hewitt is profoundly knowledgeable in all sorts of arcane subjects and possesses a ruthlessly logical mind. Like the stories of the sage of Baker Street, Hewitt’s adventures mostly appeared in the pages of The Strand Magazine and were illustrated by Sydney Paget. In other ways, though, Hewitt is Holmes’s antithesis. A lawyer’s clerk turned private detective, with offices on the Strand, he is not a flamboyant eccentric but a “stoutish, clean-shaven man, of middle height, and of a cheerful, round countenance.” In total, Martin Hewitt appeared in twenty-five short stories which were collected in four volumes between 1894 and 1903.

Addington Peace

Unlike the majority of Sherlock’s rivals, Addington Peace is not a private detective but an astute police inspector. He appears in a 1905 volume of short stories, narrated by Peace’s Watson, an aspiring artist named Phillips. Their author was Bertram Fletcher Robinson, a writer justly celebrated by Sherlockians for his role in the creation of The Hound of the Baskervilles. A friend of Conan Doyle, he told him of the legends of ghostly hounds. The Hound of the Baskervilles is dedicated to Robinson who died in 1907, aged only 36. Wild conspiracy theorists have claimed not only that Doyle stole ideas from Robinson but that he was involved in poisoning him. This seems, to say the least, unlikely.

Miss Lois Cayley

Some female rivals of Sherlock were actually created by male writers. Lois Cayley, who first appeared in a series of stories published in The Strand, is a Cambridge-educated “New Woman” of the 1890s. Traveling Europe in search of adventure and a means of earning money, Miss Cayley becomes involved in mysteries which require all her wit and intelligence to solve. Her creator was Grant Allen, a popular and versatile writer whose feminist sympathies are clearly in evidence in the stories. Hilda Wade, an episodic novel with another intrepid and intellectually adventurous heroine, was finished, after Allen’s death, by his friend Arthur Conan Doyle.

__________________________________