It was Mardi Gras night, and I was waiting in the wings of a glitzy hotel ballroom, dressed in a white gown and gloves, when I realized two things in rapid succession: first, it was probably too late to get out of this whole debutante thing; and second, I had to write a book about this.

The metaphors had already been presenting themselves like hors d’oeuvres on silver platters: a few hours before, when I was zipping into my gorgeous, corseted ball gown, I took a deep breath to steel myself…and part of the zipper popped off, flying across the room. No room for extra oxygen, then. Later, at the hotel, at least two different people congratulated me on my wedding. Nevermind that I was a twenty-year-old student, single, and clearly horrified at the implication—from my getup, I could understand the confusion.

New Orleans debutante culture, like the city itself, is wild, unique, and full of contradictions. It’s glamorous, beautiful, and a little silly, but it’s also stained with a dark history that pervades the atmosphere as thoroughly as the Louisiana humidity.

I never wanted to be a debutante. Growing up in New Orleans, I had always known that it was a tradition on my dad’s side of my family, but I also knew that the history of debutante balls—a way for the social “elites” to introduce their daughters to the marriage market—made me deeply uncomfortable. Still, when my junior year of college rolled around and I was reminded how important the tradition was to my family, I caved. These are people I love, I reasoned, to whom I owe so much of my success and happiness—why not put on a pretty dress and promenade around a ballroom if it will make them proud?

Of course, there’s much more to it than I’d realized. For one thing, making my debut was not a one-night commitment. It entailed a full “season,” complete with luncheons, elaborate parties, and presentations at multiple balls. Added to that is the Mardi Gras element: balls are hosted by different “Krewes,” social clubs that also run parades and other Carnival festivities, some of which are highly exclusive and even secretive. Not all balls are identical, but in my experience, debutante presentations tended to consist of a “royal court,” featuring debutante “Maids” and a “Queen”—young women, usually juniors or seniors in college—and occasionally a “King,” a middle-aged to elderly man from the Krewe. Despite this uncomfortable age gap dynamic, there were colorful costumes, masks, live music, dancing, and—because it’s New Orleans—plenty of liquor flowing.

On the surface, these balls are a rollicking good time, a perfect embodiment of the laissez les bons temps rouler attitude of the city. But beneath the glitter and the champagne, there’s a more sinister history lurking.

The Mardi Gras debutante tradition as we know it dates back to the 19th century, when the first Krewes were officially founded in the city. These included what are now recognized as the “old-line” Krewes—groups historically made up only of white, wealthy men of an approved “pedigree”—as well as social aid and pleasure clubs, which are rooted in the Black community.

While this sort of racial division was commonplace at the time, many are surprised to learn that it wasn’t until 1991 that the city made any move to change Krewes’ restrictive membership policies. That year, Dorothy Mae Taylor—the first Black woman to serve on the New Orleans city council—spearheaded an ordinance that would deny Mardi Gras parade licenses to any Krewes that discriminated on the basis of race, gender, or religion. While most groups complied, some of the “old-line” organizations refused to integrate; as a result, those groups had to forfeit their parades. Some of them still don’t parade to this day, hosting only private balls instead.

When I first heard this story, I was horrified—not only to learn that I was being presented by one such “old-line” group, but because of how it was framed to me. In their telling, this wasn’t an example of racism and prejudice pervading, but of a group determined to keep the city government from meddling in their private affairs. And maybe that’s true, at least to some extent, but take a look at any of these old-line balls today and it’s clear: nearly all of the debutantes—almost every face in the room, even—are white. Further complicating this dynamic is the anonymity of Krewe membership: while debutantes are presented openly, male Krewe members typically wear masks and costumes to hide their identity. In some cases, the Kings’ identities are never revealed, while their Queens’ are publicized.

Of course, all of this begs the question: why participate at all? Even after I learned about this ugly bit of history, I still made my debut. For one thing, I was twenty and terrified of disappointing my family—but putting my naivete aside, I also remember looking around at these gilded rooms and thinking, how harmful can this really be, if it’s all so ridiculous?

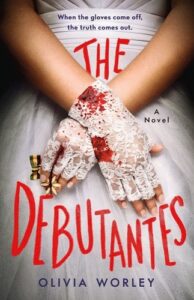

True, some things were said and done to me during my debut that haunt me to this day—like, for example, when the other debutantes and I were herded onto a stage while a room full of masked men shook cowbells at us (a detail that may or may not have made it into The Debutantes.) But when you boil it down, these debutante balls seemed to me like nothing more than wealthy people playing dress-up: they don sparkly costumes, masks, and crowns, dubbing themselves royalty as everyone toasts to the city’s favorite holiday. No one actually believes the illusion.

Do they?

When I finally sat down to write The Debutantes nearly four years later, this question was at the front of my mind. Of course, while the book is inspired by my own experiences, it’s also a work of fiction: the Krewe at its center is my own invention, and the story follows a high school debutante ball instead of a college one. Unlike the book’s protagonists, I never encountered any murderous underground cults (I promise!)

The Debutantes is, first and foremost, a fun, fast-paced YA thriller with plenty of glitz, glamour, and drama. But it also wrestles with the very real questions I was struggling with then, and even now: what do these organizations really represent, and why do people feel so tied to them, despite their increasing archaism? What does it mean to grow up and understand that the communities that raised us can be deeply flawed—and what does it mean to love them anyway?

There’s one more metaphor in The Debutantes that practically writes itself: New Orleans is sinking. Literally—as the characters in the book like to note, the city is below sea level and therefore under constant threat of flooding. We can’t even bury bodies underground, or else they might float back up. (Like, come on—I had to write a thriller set in New Orleans!)

Toward the end of the book, one of the main characters, April, revisits this idea, asking herself, “How do you love a home that’s sinking?” She comes up with her own answer, but I think I’m still writing my own. If there’s one thing I know, though, it’s this: understanding that a place is flawed doesn’t mean you stop loving it. It only means you see it more completely—the joy and the magic, yes, but also the darkness behind the dazzle, the truth beneath the mask. And from there, you can fight—and write—for the parts you believe in. Because while the debutante gown may be collecting dust in my closet, I have a feeling I’m not done writing this story just yet.

***