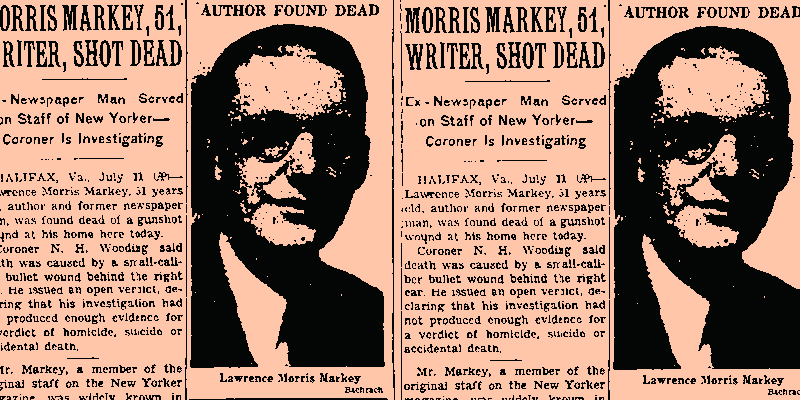

In 1950, when former New Yorker writer Morris Markey was found in the hallway of his Virginia, home, a bullet hole behind his right ear and a rifle nearby, his mother insisted it was an accident. As did his old colleague James Thurber. Markey’s wife told the police it was an accident. The next day, she confessed to family friend James M. Cain that her husband had committed suicide, making it look like an accident for insurance purposes.

Cain put his opinion into a letter to Lawrence Stallings, calling it a tale that “Tennessee Williams collaborating with Spillane could hardly have thought up.”

It was a sad end for one of the first reporters hired by Harold Ross to write for the New Yorker, a man E.B. White once called the “greatest living writer.” Given his fondness for drink and dinners at Luchow’s, few of Markey’s friends would have been shocked by a heart attack—or cirrhosis, from which he suffered. But a bullet through the back of the head suggested a range of scenarios so messy no one wanted to speculate further. Better to bury the man and leave it be.

The year he died, Markey tossed off a piece for Esquire on a cold case of a man found shot in his home. “Was it suicide—or murder?” Markey wondered. The same can be asked about his death. Some clues as to how a life ends can be found in how it begins. Lawrence Morris Markey was born in the last year of the 19th century in Alexandria, Virginia, the youngest of three in a family that had worked its way into the middle class. He left high school in junior year, trying a variety of things, ranging from working in a soap factory to leading a scout troop. War must have seemed just the thing for big, bright, restless young man. Markey joined the Red Cross in 1918. A photo of him in France shows an uncommonly tall, fair-haired boy. In his passport, he is slim and bespectacled in suit and tie, the image of a future New Yorker writer. Later in life, he grew heavier, the face fuller, more ruddy.

When he returned from the war, he started his career as a newspaper man, joining the Atlanta Journal. His big break came in 1920 when he became the subject of his own story by getting himself stabbed by a berserk lawyer. He married and moved to New York where he worked the tabloids as reporter and rewrite man before landing at The World. There he met Cain; the two became good friends, in part because Markey reminded Cain of his younger brother. “Morris was a very special case with me—for my brother was killed in a needless plane crash…that he took without being ordered to the last day of his service, as a lieutenant of the Marines. It was exactly the kind of flight that Morris would have taken.”

“What he meant to me was peculiar, an inner ethos framed with the worst brawling exterior anyone ever had.”

In 1925, Markey did a thing many thought folly: he joined The New Yorker. As the first “Reporter at Large,” his chief subject was the city itself. Gangsters, evangelists, street corner revolutionaries, boxers, and baseball players filled his columns. He took readers to Wall Street, the Tombs, and a Board of Estimates meeting in the days of Jimmy Walker.

Ross told Markey, “Be honest at whatever cost.” Much of what Markey wrote was honest and accurate—but not all of it. He was the bane of the fact-checking department, even getting into a famous fist fight with editor St. Clair McKelway at the New Yorker’s 10th anniversary party. Ross was hard on Markey and Markey was hard on Ross. The two men were scrapping as early as 1927, when Ross wrote, “I wasn’t tired of your stuff. I was tired only of your never doing a thing until the last minute, of your rushing in breathlessly on a Friday or Saturday with something that could have been written in the past six months.”

In Markey’s defense, he kept the pages of the magazine filled at a time when few writers wanted to commit to Ross’s project. And when he was good, he was very good. His provocatively breezy take on such moral hazards as gangs (“There was a terrific melee; everybody swinging at everybody else’s head, and everybody getting hurt at least a little bit, just for the honor of the thing.”) and bathtub orgies (“If you missed following this trial as it unfolded…you missed one of the most thoroughly delightful entertainments which have been vouchsafed, on Broadway or off in late days.”) fit the mood of the hedonistic 20s.

But in the 30s, things seemed to go wrong. Markey might insist that “the only thing I had a talent for was looking at a thing and trying to tell people exactly what I saw.” But it wasn’t always clear if he’d seen something or just heard about it. Thurber affectionately recalled to White, “Remember how Markey wrote an intimate account of Baltimore without ever going there?” As much as Cain admired “exquisite, precisionist style,” he also said he “would sacrifice a fact for a phrase any time.”

“His real trouble,” Cain would later write Stallings, “was booze.” Markey wasn’t alone in that affliction; both Cain and Thurber suffered. But unlike Markey, Cain and Thurber were moving beyond the magazine world. Cain broke out with The Postman Always Rings Twice. (Markey was delighted: “It is a very fine work of art and if you ain’t in the money now I am just plain crazy.”) Thurber had a huge success with “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.”

That success would please Markey less. As he wrote to Cain, Thurber “has stolen my ideas and he knows it…. His famous Mitty story—pukkyty-pukkyty—was straight from my Harper’s story called, ‘The Strange Noise of Dr. Beldoon.’”

There is a sharp whiff of burned bridge in the latter part of Markey’s life. He left The New Yorker and started writing for a dizzying array of magazines, from Liberty to The Atlantic to McCall’s. He ventured out to Hollywood, which he called “unproductive.” He wrote one of his more famous pieces on a new organization called Alcoholics Anonymous. One wonders if some caring editor assigned it, hoping he might take the hint. His sources of income increase in number, but one suspects that’s because the paychecks were smaller. At any rate, they were insufficient to the family’s needs, which included giving his daughter Sue something his wife had, but he did not: a college education.

“He became obsessed that Sue must have what he didn’t have, a college education,” wrote Cain. “[U]unquestionably [he and Helen] were strapped to the point of desperation, apparently to carry the Vassar project to completion. Then at last it was done, and they moved to Virginia, he writing me occasionally about it.”

Markey not only wrote, he repeatedly invited Cain to visit. “By God, guy, you come on down here. I need somebody to talk to, and to listen to. And you’ve got to admit that with all my gabbiness I always found it easy to listen.” Cain never went. Still Markey is grateful for the letters. “I don’t need to write a big scene to tell you how I appreciate the way you’ve been writing to me. I’ll just say it and you know I mean it.”

Then in the summer of 1950, Helen Markey called Cain with the news that Markey was dead. “[He] had been shot, with some question as to how.”

To Thurber, there was no question about it. “He was probably killed, certainly accidentally, by the very Remington rifle he once brought to Sandy Hook.… He was reckless with firearms and with automobiles, but he denied this with all his vehemence.” Helen Markey told investigators a similar story. Markey “was alone in a downstairs hall while other members were planning to retire when they heard the shot.” In her view, he fell and “the jar knocked down the rifle which had been against the wall, causing it to discharge.” But after the funeral, she told Cain a different tale. Markey had told her that when he died, she wouldn’t have to worry: it “would be an accident and she’d collect.” He had been so despondent—and so clear in his intentions—the family had hidden the rifle.

The author of Double Indemnity did not suspect Helen Markey of shooting her husband. But he seems to have wondered if she wasn’t protecting someone else: her daughter.The author of Double Indemnity did not suspect Helen Markey of shooting her husband. But he seems to have wondered if she wasn’t protecting someone else: her daughter. According to Markey’s older brother, Marvin, the “real trouble was Sue.” After Sue graduated, the family moved to Halifax. Sue got engaged. Her father did not approve. In his letter to Stallings, Cain wrote, “After he’d spent all that money sending her to college and all, he thought she owed herself, as well as her education, not to marry the first country boy who asked her for a date. (I told you there was a Tennessee Williams angle to it.)”

“Sue drove out one morning on some errand at a store and saw four little puppies out on the side of the road, where someone had dropped them… So she stopped, gathered the puppies up and took them home.” Then Cain reports, “she went in to get the rifle, the .22 they had, to shoot them—and did.’” In brother Marvin’s telling, Sue Markey left the rifle in the hallway when she went to bury the puppies. Her father found it and made good on his promise, possibly standing the rifle upright and leaning down to fix it behind his ear.

It is difficult to get past the image of Sue Markey shooting puppies—an act that makes even professional tough guy James M. Cain “retchy.” It colors our understanding of her “accidental” placement of the rifle where her father could get it. In Helen Markey’s telling, the death occurred at night. In Marvin’s, it almost certainly took place during the day, given Sue’s trip into town. Strangely, two times of death are noted in the death certificate: 11:30 AM and 11:30 PM. Cain’s scenario of Sue shooting her father only makes sense if death occurred at 11:30 AM. If the time of death is 11:30 PM, then Helen Markey’s claim that her husband had stayed up late drinking, knocked the rifle over, causing it to fire makes more sense. As does her claim of suicide. When asked to check Accident, Suicide, or Homicide, the coroner wrote Unknown.

Was Cain correct? Did Sue Markey either shoot her father or intentionally leave the rifle out? Did her mother lie to protect her? She does not seem to have had a happy life. In 1965, she was in Jacksonville FL., more than 500 miles from her home, when she died at the age of 36. On her death certificate, her name is listed as Sue Markey Bennett (alias). Typed beneath that is the name Sue Markey Caldwell. The official cause of death was bronchopneumonia and cerebral edema due to chronic alcoholism. But if Sue or her husband did kill her father, it’s strange that they did not leave town. They lived in South Boston, close to where he died. Perhaps we should believe Helen Markey’s version: that he committed suicide, over the pain of cirrhosis and the mental anguish of a lost career.

Let’s go back to that short story he accused Thurber of stealing: “The Strange Noise of Dr. Beldoon.” In the story, first published in 1939, a doctor sits down to write an angry letter to a patient who has not paid his bills when he hears a “low hissing sound just behind his right ear.” Unnerved, he decides to put off writing the letter. The next morning, he finds the payment on his secretary’s desk. The hissing comes again when he is about to operate on a child; the scalpel has not been sterilized. “How fortunate, he thought, to be blessed with this remarkable insurance against error.” Then one day a friend is in a car accident. His leg is crushed; Dr. Beldoon knows he should amputate. But he doesn’t want to make his friend a cripple. He begins by setting the bones—and hears the hiss. Miserable, he obeys and amputates the leg. He falls into a depression. One night, he decides to destroy the noise. He knows where it is hiding. He shoots himself behind the right ear, the exact spot the bullet entered Markey’s skull eleven years later.

Thurber wrote “I mourn the untimely passing of a great friend, a highly talented writer, and a vivid and vital human being.” Cain’s eulogy is sadder. He concludes his account to Stallings, “So that’s about all I can tell you—at least what I feel I could write…. Morris had developed a mania for lousing things up…. like most real life things, my story has no point, climax, or beauty. However, you asked for it, so such as it is, you have it.”

***