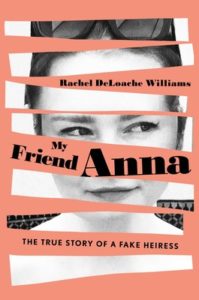

In October 2017, the con artist, fake heiress, and Instagram influencer Anna Sorokin, who called herself Anna Delvey, was arrested for swindling approximately $275,000 from various high-end entities. Known as the Soho Grifter, she scammed $62,000 from Rachel DeLoache Williams, a young Vanity Fair employee she befriended.

____________________________________________

I was six years into my job at Vanity Fair when she appeared. From the get-go, there was something about her that demanded attention, an enigmatic otherness that was captivating. I met her one night when I was out with friends. It’s funny in hindsight to consider the impact of such an otherwise unremarkable evening. Although Anna struck me as a bit odd, meeting her would have been forgettable had it not set into motion a chain of events that would alter both of our lives forever.

It was a Wednesday in February 2016, a few weeks after my twenty-eighth birthday. I had just recovered from a nasty cold, which had kept me cooped up for several days watching The Great British Bake Off, a television series I had recently discovered and had become obsessed with. Vanity Fair’s annual Hollywood issue was on newsstands, its cover featuring thirteen women, including Jennifer Lawrence, Cate Blanchett, Jane Fonda, and Viola Davis.

As usual, I went to work at Vanity Fair’s headquarters, now located on the forty-first floor of One World Trade Center, the tallest building in the United States, into which Condé Nast had moved two years prior. I spent the morning catching up on my expenses: tracking down receipts for charges that had been made on my credit card before and during photo shoots. I taped down each receipt, carefully entered its details into an online portal, and then typed in the assignment code that tied each charge to its corresponding project. I finished the report after lunch, scanned in the receipts, and clicked Submit. Within a few weeks, Condé Nast would approve the line items and disburse payment directly to American Express. The rest of the workday was slower, mostly emails back and forth pertaining to upcoming shoot dates. By 5:30 p.m., I was antsy from a day of paperwork and in the mood to socialize. I sent an email to my colleague Cate, to ask if perhaps she wanted to have dinner together. She had plans already but suggested we grab a quick glass of wine. We went to P. J. Clarke’s in Brookfield Place, close to our office. She had to leave after forty-five minutes, but I settled in to order food.

Maybe it was that glass of wine or the slowness of the workweek. Maybe I was on a high after my sickness or especially liked the outfit I had on. Whatever the reason, on that particular evening I was full of energy and eager for some fun. As Cate left, I scrolled through my phone to plan my next move.

I sent a text to my friend Ashley, an upbeat blonde with good lipstick sense and a kind heart, whom I’d known since the first summer after I moved to the city. Back then, she was working at Interview magazine with one of my best friends from college. Ashley had since found her way through the fashion editorial scene to become a freelance writer. She would travel to parties, events, and fashion shows and then write about them for publications such as Vogue, AnOther Magazine, W, and V. She was always fun to be around, and it was Fashion Week, so there was a chance she would already be out and game for an adventure.

Hi!! I just finished my last show! she quickly replied. Want to grab a drink maybe?

That was exactly what I wanted. We made a plan: I would finish my dinner, she would wrap up some of her Fashion Week coverage, and then, at eight p.m., we would meet at Black Market, a cocktail bar in Alphabet City.

She arrived on schedule and got us a table. Because of a pit stop in my apartment (to drop off my workbag and change into boots with more of a heel), I walked in fifteen minutes late, full of apologies. The two of us were cheerful as we caught up over cocktails. In a few days’ time, Ashley would travel to London Fashion Week and then to Havana before another week of fashion shows in Paris.

Once our drinks were finished and we had caught up on each other’s news, we decided to join forces with some of Ashley’s fashion friends who were also out that night. We walked twenty minutes to meet them at a place called Happy Ending, a trendy spot on the Lower East Side with a restaurant on the ground floor and a popular nightclub past the bouncer one flight down.

We found our group finishing dinner, tucked into a booth in the back. Mariella was there, an Australian with short brown hair and a natural sassiness that was endearingly exaggerated by her accent. I’d met her recently through Ashley. She worked in PR for luxury brands. There were a couple of other girls there, too, whom I didn’t know that well: a fashion associate from a Hearst magazine and a publicist who worked in-house for a fashion label.

Tagging along with this crowd made me feel like I was on the inside of something special. Their knowledge of fashion and a certain slice of who’s-who trivia exceeded my own, but I knew the language and got the jokes.Tagging along with this crowd made me feel like I was on the inside of something special. Their knowledge of fashion and a certain slice of who’s-who trivia exceeded my own, but I knew the language and got the jokes. They were friends with publicists, models, musicians, and designers. Wherever we went, they knew the guy at the door—the one who decides if you’re tall enough, rich enough, or attractive enough to enter; who might, if he’s in the right mood and you know the right person, say the right thing, or wear the right shoes, let you pass. Select patrons only—it’s a funny idea. Why is exclusivity appealing? We all want to be included. We crave validation, from friends and from strangers. If you’d said that to me then, I’d have been defensive. I might have said, “Oh, sure, the door is silly, but inside you’ll have more fun than you would in some other random bar,” and I’d have been right. On this night in particular, I wish the door policy had been even more discerning.

Tommy came by the table as the dinner plates were cleared. “Tommy” was a name I’d heard mentioned many times. In his early to mid-forties, from Germany by way of Paris, he worked with businesses on the creative direction of their branding, marketing, and events. I knew him as someone who threw exclusive parties for Fashion Week types—in an assortment of popular venues (from hot-spot hotels like the Surf Lodge, in Montauk, to buzzy nightclubs like the once fun, now defunct Le Baron in Chinatown). If you were looking for him in a crowd, you could ask any stranger. “Oh, Tommy? He was just here a minute ago” would be a likely response. He always—and I mean always—wore a hat.

It was thanks to him that we had a reservation in the more exclusive lounge downstairs. We walked in as the space was kicking into gear, not empty but not crowded. Young men and women made laps through machine-pumped fog, scouting for action and a place to settle in, as they sipped their vodka soda through black plastic straws. We made our way to the right and back, where the fog and people were denser and the music was louder. We spilled onto the banquette and small stools flanking a low, round, red-topped table.

After scrolling through her posts—pictures of travel, art, and a few doe-eyed selfies—I assumed that she was a socialite.I can’t remember what arrived first: the expected bucket of ice with a bottle of Grey Goose and stack of glasses or “Anna Delvey.” She was a stranger, and yet not entirely unknown to me. I’d noticed her for the first time one month earlier, tagged in Instagram photos with Ashley and other girls whom I had recognized. Curious about the unfamiliar face, I’d clicked the tag over her image and discovered that @annadelvey (since changed to @theannadelvey) had more than 40,000 followers. After scrolling through her posts—pictures of travel, art, and a few doe-eyed selfies—I assumed that she was a socialite. She smiled and made herself at home in our company, a relaxed, new member of the crew. I was looking forward to meeting her.

Anna, in a clingy black dress and flat black Gucci t-strap sandals with gold bamboo-inspired accents around the ankle, slid into the banquette on the other side of Mariella, who was sitting to my left. She methodically smoothed her long auburn hair, arranging it over her shoulders, as Mariella introduced us. Anna had a cherubic face with oversize blue eyes and pouty lips. She greeted me in an ambiguously accented voice that was unexpectedly high-pitched.

Pleasantries led to a discussion of how Anna first came into our group of friends. She had interned for Purple magazine in Paris and become friends with Tommy back when he was living there, too. It was the quintessential nice-to-meet-you-in-New-York conversation: hellos, exchange of niceties, how do you know X, what do you do for work?

“I work at Vanity Fair,” I told her. The usual dialogue ensued: “In the photo department,” “Yes, I love it,” “I’ve been there for six years.” Anna was attentive, engaged, and generous, ordering another bottle of Grey Goose and picking up the tab. I could tell that she liked me, and I was happy to have found a new friend.

Not long after that evening, I was invited by Mariella to join her and Anna for an evening at Harry’s, a downtown steak house not far from my office. It was the first time Mariella had reached out to me directly, and I was pleased. Until then, we’d only seen each other when I was out with Ashley, whom I knew best out of the group.

The vibe at Harry’s was masculine and upscale, with leather seating and wood-paneled walls. Anna was there when I arrived, and Mariella came a few minutes later, impeccably dressed, having rushed from a work event. We were shown to our table and we settled in, removing our jackets and setting our bags to the side. These girls are pretty cool, I thought to myself, slightly nervous and aching for a cocktail. Anna was testing out an app for a friend, she told us. She had used it to make our dinner reservation and would also use it to pay. I wasn’t hungry—we’d had pizza that afternoon in the office—but Anna ordered appetizers, entrées, several side dishes, and a round of espresso martinis for the table.

Conversation rolled along just fine, as did the cocktails. The evening had a distinct New York glamour to it—martinis in a steak house, chatting about our workday.

Mariella went first, filling us in on the successful PR event she’d finished just before dinner. Then I told her and Anna about my day, which was unexceptional by comparison. Last up, our focus turned to Anna. She had spent the day in meetings with lawyers, she said.

“For what?” I asked.

Anna’s ambitions, in particular, were remarkable—her plans were grand in scale and promising in theory—but what was just as fascinating, if not more so, was her hypnotizing manner.Anna’s face lit up. She was hard at work on her foundation—a visual-arts center dedicated to contemporary art, she explained, referring vaguely to a family trust. She planned to lease the historic Church Missions House, a building at Park Avenue South and Twenty-Second Street, to house a lounge, bar, art galleries, studio space, restaurants, and a members-only club. She was meeting every day with lawyers and bankers in an effort to finalize the lease. I was impressed. Anna and Mariella embodied a level of professional empowerment that I respected and wanted to emulate. Anna’s ambitions, in particular, were remarkable—her plans were grand in scale and promising in theory—but what was just as fascinating, if not more so, was her hypnotizing manner. She was endearingly kooky, not polished or prim. Her hair was wispy, her face was naked, and she was constantly fidgeting with her hands. She was a zillion miles away from the cotillion-trained debutantes I’d known in my youth, and I liked her more because of it.

The evening went on, more food arrived, and finally it came time for the bill. Anna offered her phone to the waiter, who obligingly studied its screen.

“I don’t think it’s working,” he said.

“Are you sure?” Anna asked. “Can you try it again?”

The waiter took the phone to a computer across the room and typed in the numbers manually before coming back to us a minute later.

“I’m sorry, there’s still an error,” he said, returning Anna’s cell phone. Mariella and I assuaged Anna’s obvious frustration with the offer of our credit cards. It had been a nice evening with new friends, and even though I hadn’t eaten more than a few oysters, I was happy to take on a third of the check, less for the food and more for the pleasure of the company. I thought nothing more of it.

I got together with Ashley, Anna, and Mariella every few weekends. Our friendship was filled with late nights in SoHo and occasional after-work events. We once went to one of Mariella’s functions—a book launch at the Oscar de la Renta flagship store on the Upper East Side—where we crossed paths with real estate developer Aby Rosen, whose company, RFR Realty, owned the building Anna was working to lease. When Anna spotted him, she walked over excitedly to say hello. I watched from across the room, marveling to see an assertive young woman holding her own in conversation with such a prominent businessman.

Nights would start with Ashley and me making plans to meet for drinks. By the end of our hang time, a group would have joined us. One at a time they would arrive: Mariella, Anna, and sometimes others. We had a more-the-merrier mentality, and those New York nights had a flow: we’d start at a restaurant, stop by a bar, and end with a dance floor or two. Most of the places we frequented have since closed and their names have been forgotten. Whatever their particular theme, they were iterations of the same core concept, designed to draw the fashionable crowd of the moment.

____________________________________________