I was a visual artist long before I was a writer, but I was always haunted. By the ghost of my beloved childhood cat, who sometimes ran past me down the hall long after she’d passed on. By the scent of cigarettes that sometimes drifted into the house we’d inherited from my grandparents after my grandmother, a lifelong smoker, died. By the ghosts that seemed to live in my own mind, the many fears of clowns and aliens and monsters I conjured lying awake at night. I was telling stories to myself, and then I was telling my stories with paint and clay.

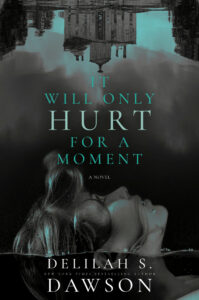

My next book, It Will Only Hurt for a Moment, is about a similarly haunted artist—one who discovers a dark secret. Sarah Carpenter is a potter who abandoned her medium for the wrong man and now seeks to escape that abusive relationship by running away to a remote artists’ retreat in the north Georgia mountains. She hopes to reconnect with her muse in a beautiful valley surrounded by likeminded artists, watched over by the sprawling old resort hotel once beloved by America’s high society. But when Sarah accidentally discovers a body while digging a pit kiln, things start to go wrong. Sarah—and her fellow artists—connect with something long dead, a voice desperate to be heard. As it turns out, artists are tuned into another frequency. We often say our ideas come from some other place, but we don’t necessarily want to know where.

That’s why artists are such a ripe community for horror stories. We open ourselves up to possibility and welcome whatever clambers inside.

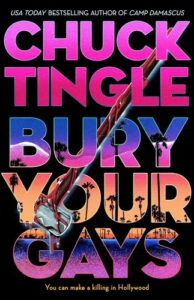

First of all, let’s remember that writers are artists, too. In Chuck Tingle’s Bury Your Gays, a successful Hollywood screenwriter is finally on the cusp of making it big at the Oscars when the studio bigwigs force him to do the most predictable and soul-killing thing: kill off his gay characters to suit the algorithm. When he refuses, horrifying monsters from his own creations begin to stalk him, breaking the line between reality and fiction. Since the protagonist is a writer and the book is in first person point of view, the reader is treated to beautiful, thoughtful moments where Misha considers the relationship between the writer and story and how past trauma always finds a way in.

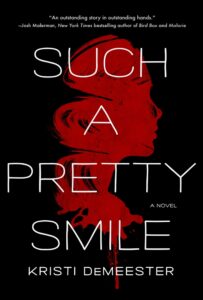

But some artists are not so self-aware. In Such a Pretty Smile by Kristi DeMeester, an artist mother and her teen daughter are both caught up in the cycle of the same serial killer, known only as the Cur because his victims are found with bite-riddled thighs. While the daughter struggles with the opposing urges to fit in and act out, her mother creates beautiful but eerie sculptures while in a trancelike state—artworks somehow related to the tragedies in her past that she can’t quite remember. Personally, as someone who has painted with my own blood, I’m always here for the admixture of female rage and art.

Speaking of female rage, I recently had the opportunity to interview Lilliam Rivera here on CrimeReads, as we both wrote books that merge fashion with horror. We discussed my recent novella, Guillotine, and Rivera’s novel. Tiny Threads, which follows a hopeful fashion executive as she moves from New Jersey to Vernon, California, to pursue her dream job with a world-renowned designer. But behind Vernon’s flashy, bougie façade lies the stink of a slaughterhouse—and years of abuse and exploitation. As Lilliam’s protagonist, Samara, tries to connect with both the bigwig design team and the reserved, ignored women who sew the garments, she’s torn between her future and the past, reality and insanity, fashion and poverty. Samara is an artist of words and the descendant of a seamstress struggling to find her own voice, and she, too, is driven mad by her own repressed darkness.

So that’s clay, screenplays, sculpture, and fashion, but there’s something to be said for actors and the fact that their art requires them to hide behind a mask. In If We Were Villains by M.L. Rio, our cast of characters is embroiled in the works of Shakespeare at a small and selective conservatory. Each character has a roll to play that fits neatly into the company: the villain, the hero, the tyrant, the temptress, the ingenue, and the two leftovers forced to play sidekicks and bit parts. But when some of the roles are switched for a Halloween rendition of Macbeth, all hell breaks loose and someone ends up dead. The mystery behind this violence is as intricate and curious as Rio’s language, which draws from the poetry of Shakespeare to immerse the reader in a haunting dark academia world akin to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. And maybe it’s just me, but I’m a sucker for a book with a skull on the cover.

In these stories, and in life, art and horror go hand in hand because… well, lots of art springs from the darker emotions. Fear, anxiety, anger, pain. Art allows us to find the order in that chaos, to create an evidence board more beautiful than a bunch of red string and pushpins and see all the available data laid bare, exposed to the light. Through art, we work through our thoughts and give them shape and depth. Through art, we find a path forward. Through art, we find the light.

But when you open a window to let in the sun, anything might crawl inside. There’s a reason Aristotle said, “There is no great genius without some madness.” Artists are ripe for horror because they are already accustomed to living in a world of imagination and story, to seeing and hearing things other people miss entirely, to existing on another plane. And because of that openness, that sixth sense, they are uniquely vulnerable to haunting, stalking, and torture.

On the page. Not literally.

Please do not torture your local artist. Honestly, we do it to ourselves.

***