Growing up, there wasn’t much to do in my hometown other than lap the mall and raid the local video store so, like many American teenagers, my first taste of freedom came the day I passed my driving test.

That first summer behind the wheel of my parents’ ancient Chevy Lumina, I spent countless hours driving nowhere in particular, soaking up my newfound independence. I would blast Ani DiFranco over the stereo and dream about the wider world that was suddenly within my reach, and all the roads I had yet to drive.

I was also, if I’m being honest, scared half to death.

Out in the suburbs, there’s a certain pernicious sense of hidden danger lying beneath the manicured surface. Anyone who grew up watching Unsolved Mysteries is all-too familiar with the fact that there were dark dangers tucked in the woods behind in the well-lit houses, perverts lurking in the lilac bushes, cold-blooded killers waiting to strike.

Hunched over the wheel, eyes fixed on the two spots of light the headlights cast on the otherwise-dark road, I would work myself up into an almighty terror. At any minute, it seemed to me, some red-eyed lunatic would jump in front of my car, or slash my tires, or appear in the rearview mirror, murder in his eyes.

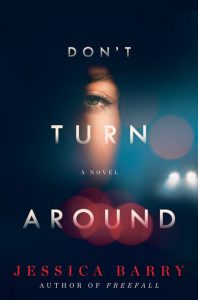

It’s this particular terror that inspired my new novel, Don’t Turn Around. In it, two women drive through the night across the New Mexican desert. When a pair of headlights emerges from the dark and begins relentlessly pursuing them, they find themselves hurtling down the highway in the fight of their lives.

Books and film have long capitalized on the fear of the chase. Think of the sickening fear induced by the filthy, faceless, grunting tank truck in Steven Spielberg’s 1971 classic, Duel. The premise is simple—man passes truck on deserted highway, truck goes berserk—but its terror is absolute, and as we watch the truck in relentless pursuit of the hapless salesman, we can easily imagine ourselves behind the wheel.

There are few chase scenes as relentless as Chigurh’s pursuit of the hapless Llewelyn Moss in Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. He is patient, methodical, unremitting to the point of tedium. And yet it’s this slow, deliberate pace that holds the reader so tight. Chigurh seems less like a man and more like a bullet traveling on a slow, steady trajectory aimed squarely at Llewelyn’s heart. We don’t know when it will hit its target, but we have no doubt that it will, and that when it does, that the shot will prove fatal.

Another brilliant slow-burn is Dorothy L Hughes’ 1962 noir masterpiece, An Expendable Man. In it, a young doctor is driving from his home in Los Angeles to a family wedding in Phoenix, Arizona. A woman flags down his Cadillac on a stretch of dusty highway and, despite misgivings, he agrees to give her a lift. His initial instincts prove correct as the hitchhiker inveigles her way into the doctor’s life in sinister, life-altering ways. This is a novel that’s heavy with dread, and the famous final twist is both shocking and illuminating, casting new light on the risk the doctor took by letting strange woman into his car.

To my mind, one of the greatest car chase scenes ever committed to the page comes from Austin Wright’s novel Tony and Susan, which became the basis for the Tom Ford-directed film Nocturnal Animals. The scene opens with a family traveling on the interstate in the middle of the night. The road is close to empty; there’s a road rage incident, followed by an accident. The father, Tony, insists on stopping, even though his wife and teenage daughter beg him not to. But Tony feels compelled to do the decent thing, so he pulls over. This, of course, proves to be a fateful mistake, and changes the course of his life forever.

I’ve read that scene a half-dozen times, and its effect has never lessened. The desolation of the road, the terror of headlights bearing down, the helplessness of the family alone in their car, and sudden shock of horrific violence. The scene only lasts a few pages, but it stays with the reader long after, because the fear he conjures up is so real. He makes it all-too-easy for us to imagine making the same choices that Tony makes, and—God forbid—watching our own lives spin out of control.

I’m back behind the wheel these days, after fifteen car-free years in London. Every time I turn the key in the ignition and feel the engine rumble to life, I get that same spark of excitement that I did as a teenager. But I’m also a more cautious driver than I was back then, more inclined to assume the worst in other drivers. That’s the thing they don’t tell you about hitting the open road: the more you see of the world, the more you know to fear it.