As unjust as this might be, Stanley Ellin isn’t usually thought of as having contributed greatly to the 20th-century development of private-eye fiction. When he’s remembered at all nowadays, it is for his award-winning short stories, most of which debuted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (EQMM), and some of which were adapted as episodes of TV suspense series such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Ghost Story, and Tales of the Unexpected. But then, it was as a short-story writer that Ellin initially made his mark.

Born in the working-class Bath Beach district of Brooklyn, New York, in 1916, Stanley Bernard Ellin went on to graduate from Brooklyn College at age 19, try his hand at such occupations as steelworker, dairy farm manager, and teacher, and be discharged in 1945 from wartime service with the U.S. Army. Shortly after leaving college, he’d married a former classmate named Jeanne Michael, who established herself as a freelance editor (and, he said, “a brilliant, remorseless, and objective critic”). It was apparently she who convinced her literature-loving spouse to become a full-time fictionist—a decision that may have seemed rather imprudent at the outset. Indeed, Ellin’s first story, “The Specialty of the House” (about a restaurant boasting a sinister signature dish), was rejected multiple times before EQMM finally published it in 1948. However, that abbreviated yarn—now considered a crime-fiction classic—led to dozens of others, and eventually helped earn him prominence. “No short-story writer ever achieves actual perfection,” observes the blog of America’s Short Mystery Fiction Society, “but no short-story writer ever tried harder to achieve it than Stanley Ellin. And few came closer.”

Although Ellin won a couple of Edgar Allan Poe Awards from the Mystery Writers of America for his short fiction, it wasn’t solely in that field he excelled. Over the course of his 40-year career, he produced more than a dozen novels. They ranged from his 1948 revenge tale, Dreadful Summit, to 1972’s Mirror, Mirror on the Wall (a work about sex, macho self-hatred, and violence that British author H.R.F. Keating included in his 1987 list of the 100 best crime and mystery books), to 1985’s Very Old Money, focusing on out-of-work schoolteachers who join the servant staff of an affluent family that can’t seem to dust the skeletons from its closets.

In addition, Ellin concocted four gumshoe narratives, each impressive in its own way, and at least the first two of them meriting mention among the last century’s most distinctive such works.

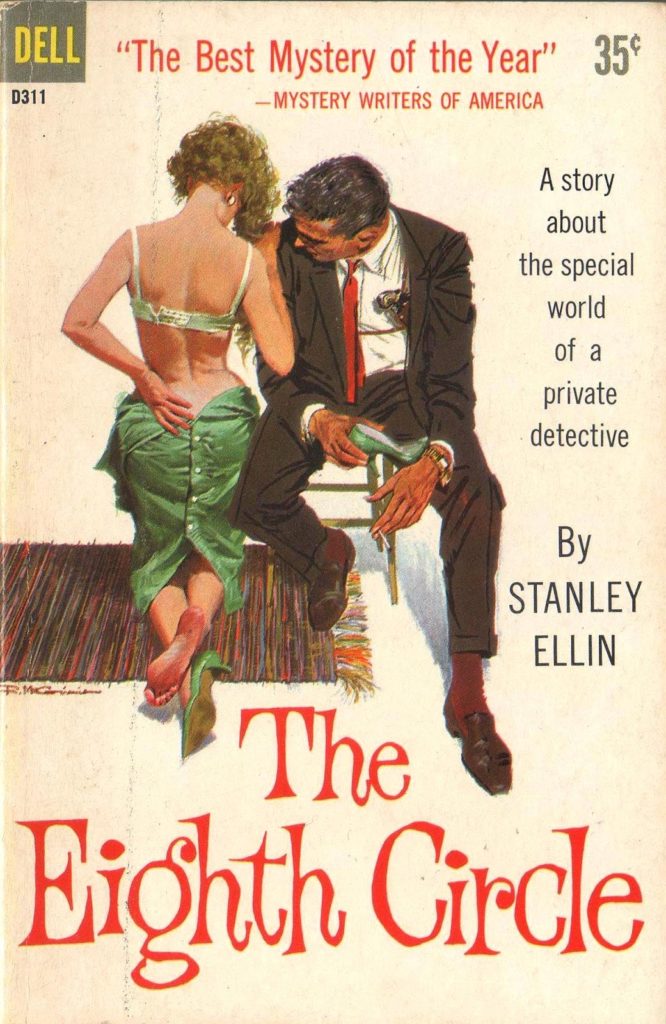

The Eighth Circle (1958)

Being a perfectionist, Stanley Ellin didn’t embark on composing The Eighth Circle, his first and best-recalled book starring a private investigator, without preparation. “Ellin studied several P.I. agencies before writing the novel,” explains Kevin Burton Smith of The Thrilling Detective Web Site, “so The Eighth Circle is a far more authentic look at real P.I. work than most P.I. novels.” His labors were rewarded: The Eighth Circle captured the 1959 Edgar Award for Best Mystery Novel.

This yarn introduces us to Murray Kirk, the 30-something son of a New York City grocer and wannabe poet. He used to be a lawyer, but not too successfully, so at a colleague’s recommendation he applied for a position with Frank Conmy’s upscale Manhattan firm of confidential inquiry operatives, and was engaged on the spot. The work turned out to be better than clerking in a law office, but it didn’t quite comport with Kirk’s preconceptions of life at a detective agency. Early on in the novel, he remarks to Conmy’s prim secretary, Mrs. Knapp, that:

“It’s not much like the movies, is it?”

Mrs. Knapp looked at him shrewdly. “No, it isn’t, Mr. Kirk. We don’t supply booze, blondes, or bullets. As a matter of fact, no one here is licensed to carry firearms except Mr. Conmy himself, and I very much doubt if Mr. Conmy knows one end of a gun from the other. Get it into your head, Mr. Kirk, that we are a legitimate business firm, authorized by the New York State Director of Licenses to perform certain lawful services. And you, young man, are as much bound by the laws of this state as the next person. I trust you’ll always keep this in mind.”

Article continues after advertisement

Readers who like their P.I. stories plump with fisticuffs and firearms might be disappointed with The Eighth Circle. There isn’t even a gun drawn until deep into Ellin’s story—and it turns out to contain no bullets. It’s just a threatening tool. But there are plenty of compensations for that lack of weaponry.

A decade after Kirk joined Conmy’s organization, and became the founder’s protégé, Conmy has passed away, leaving the business—along with his top-end apartment overlooking Central Park—in Kirk’s care. Everything seems to be going well for Ellin’s protagonist until he’s presented with the case of Arnold Lundeen, a vice squad cop caught up in an extensive corruption scandal linked to a city-wide betting ring. Lundeen’s idealistic lawyer approaches Kirk for help, and he makes a decent case for why Kirk could do some good for the accused policeman. But what ultimately secures this high-living sleuth’s involvement in the matter is Lundeen’s fiancée, schoolteacher Ruth Vincent, an ebony-tressed, long-lashed lovely (“it was incredible,” Kirk muses, “that a cop, a dumb, dishonest New York cop, should ever have come into possession of anything like this”). It doesn’t take long for Kirk to grow more interested in being with Ruth than he is in keeping her boyfriend free of the slammer. In fact, Kirk reasons that if he could somehow reveal Lundeen’s guilt without leaving behind evidence of that perfidy, Ruth might be more vulnerable to his own wooing.

In many respects, Murray Kirk is the archetypal Ellin peeper. He’s clever and successful, well-connected and far from world-weary, with big-city swagger and expensive tastes. He demonstrates few of the self-sacrificing and noble motives common to so many of his fictional ilk, but instead possesses “a businessman’s sense of ruthlessness and priorities,” as Robert A. Baker and Michael T. Nietzel put it in their 1985 survey of American detective fiction, Private Eyes: One Hundred and One Knights. The trouble for Kirk in The Eighth Circle is that his professionalism gets in the way of his selfishness. Thanks to the example of Frank Conmy, he’s turned into a fine detective and even a fine man, despite his self-doubts. The more Kirk tries to direct his latest case to his personal benefit (an endeavor not lost on his veteran employees), the more he learns to respect—even envy—Lundeen’s attorney, and the clearer he recognizes his cop client’s innocence. How, then, can he go through with his scheme to live with Ruth and still live with himself?

Far from endeavoring to “transcend the genre,” this character-propelled book sought to enrich it, to give it a broader, if less heroic scope. “The crime-fiction genre offers the writer infinite diversity of theme and treatment,” Ellin is quoted as having said. “I like to take advantage of that diversity.” With The Eighth Circle—one of my favorite private-eye novels of all time—he certainly fulfilled that goal.

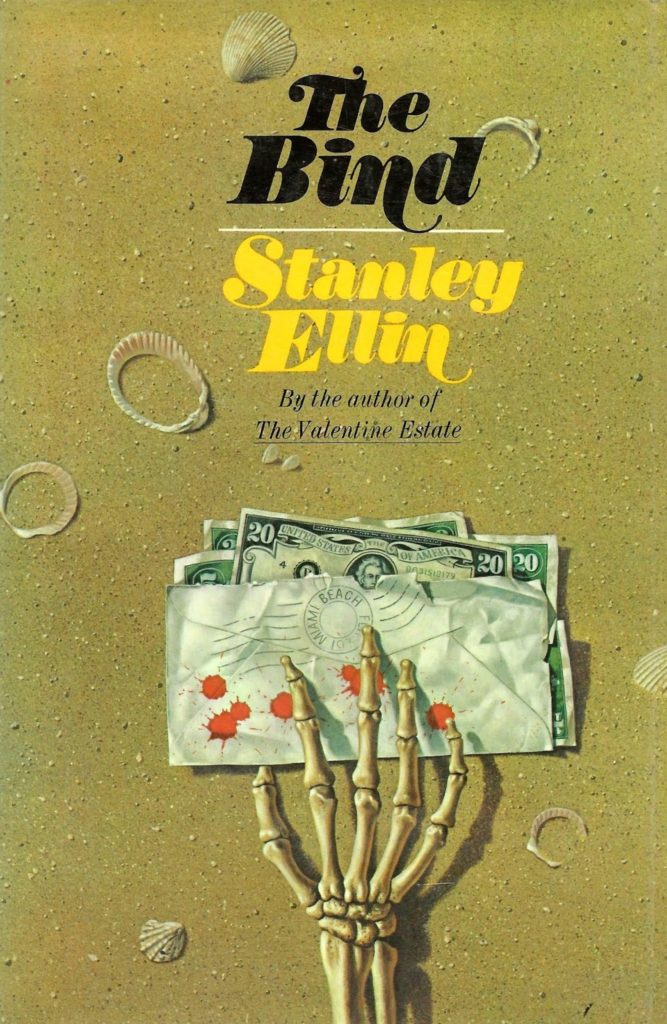

The Bind (1970)

Twelve years and half a dozen books later, Ellin returned to P.I. fiction with The Bind. Set in Miami Beach, Florida (where the author maintained a second residence), its lead role goes to Jake Dekker, a former Gotham newspaper reporter turned freelance insurance investigator. Dekker’s selfish and calculating streak is even less well concealed than Murray Kirk’s.

The plot finds Dekker hired by New York-based Guaranty Life Insurance Company to determine whether the recent demise of a middle-aged policy holder, Walter Thoren, can be blamed on an accidental car wreck (in which case Thoren’s widow collects a double-indemnity payment of $200,000) or was the consequence of suicide. The cops found no mechanical problems with the automobile and no intoxicants in Thoren’s system. Dekker, though, has evidence that Thoren, who grew rich heading up his late father-in-law’s photo-processing outfit before retiring, had experienced money troubles over the last two years, and he believes Thoren may have been the target of a blackmail scheme. If he can prove the man died by his own hand, and convince his widow to drop her suit for payment, Dekker will collect $100,000.

He enlists in his undercover plan a shapely, blonde, and loquacious part-time actress named Elinor Majeski—a naïve 21 years old to his 35—and the two of them proceed to masquerade as husband and wife at a rental property right next door to the Thorens’ home, situated in an exclusive (read “no Jews”) community outside Miami Beach. Elinor gets busy modeling bikinis in hopes of extracting information from Thoren’s concupiscent son. At the same time, Dekker plants bugs on nearby phones and seduces (for a worthy cause, of course) a lustful Latina neighbor who’s convinced that Thoren was murdered for having once sided with saboteurs intent on toppling Cuba’s Fidel Castro. With the case becoming ever more convoluted and dangerous, Dekker turns for additional assistance to an aged but honest shamus named Abe Magnes, who better understands the local ropes and players.

Thoren’s widow flees as this storyline twists; mobsters and Everglades yokels enter the picture; and suspicions are raised that Thoren’s premature passing may link somehow to intrigues dating back to World War II. Despite her conviction that Dekker is cold-blooded and singularly money-driven, Elinor starts to develop romantic feelings toward him—which only heightens this tale’s tensions as she’s attacked during an ocean swim and later endangered by flying bullets. It doesn’t take a genius to see that Dekker made a mistake bringing her into this enterprise and that he was right when he cautioned Elinor not to weigh her needs against those of his doing his job (“You’re in for a terrible disillusionment if you do”).

The atmosphere of Ellin’s story turns progressively more ominous, and its conclusion, though satisfying, is fairly shocking. So Hollywood’s decision to convert The Bind into a 1979 comedy-romance picture titled Sunburn must have made the novelist’s eyes roll all the way back to his heels. Farrah Fawcett, then at the height of her jiggle-glam fame after starring in Charlie’s Angels, was cast as a distinctly vapid Elinor opposite deadpan comic actor Charles Grodin as Dekker, with the great Art Carney wasted in the Magnes role. Filmmaker/critic Peter Hanson opines in his blog, Every ’70s Movie, that Sunburn is “neither amusing nor seductive,” and “bombard[s] the audience with stupid attempts at bedroom farce and high-stakes action.” You’re better off skipping the flick and finding the book.

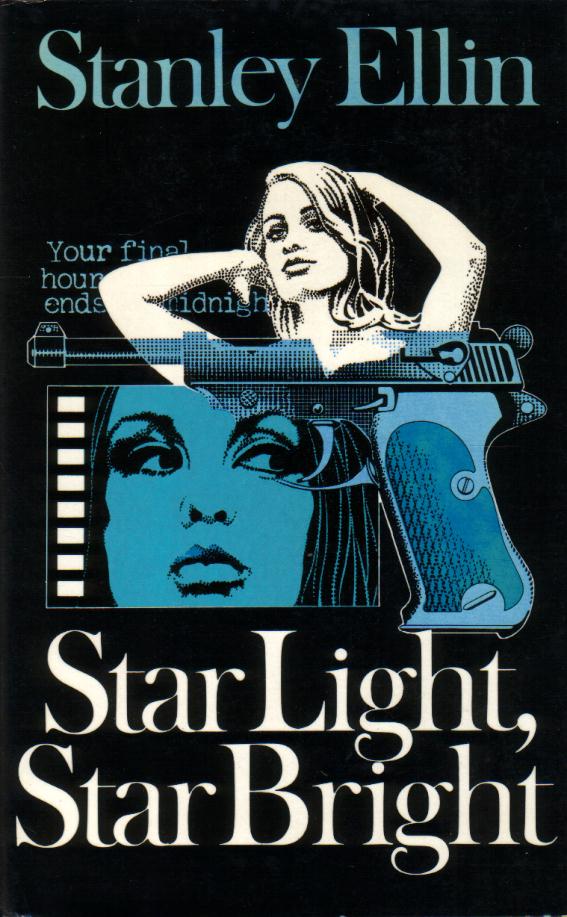

Star Light, Star Bright (1979)

Baker and Nietzel note in Private Eyes that Ellin’s snoops-for-hire are typically motivated to take on an investigation by “an obsession with a woman for whom the case becomes the way by which her love can be captured.” That was true in The Eighth Circle, and it’s equally accurate when appraising Ellin’s final two gumshoe novels.

Star Light, Star Bright throws us into the company of John Anthony Milano, whose “Johnny” nickname seems at odds with his cultured demeanor and—as with Murray Kirk—his urbane preferences in clothes, champagnes, girlfriends, and office décor. Like his creator, Milano grew up in Bath Beach, and his mother and “hotshot lawyer” of an elder sister still live in Brooklyn. Milano, on the other hand, has done his best to shed any hint of humble roots. He claims a ritzy apartment in a Central Park South co-op, drives a Mercedes-Benz, and—after years spent handling security and detective responsibilities for “fancy hotels”—is currently a full partner in Watrous Associates, a Madison Avenue private investigations agency.

Unlike Ellin’s previous P.I. outings, Star Light, Star Bright is a first-person account, with narrator Milano being summoned to Miami by Sharon Bauer, a former film celebrity of German-Mexican descent, who Milano rescued from trouble in London three years ago. The pair thereafter became lovers…until the younger Sharon ditched Milano at the behest of Walter Kondracki, a con man and “astrologer to the stars,” who insisted she instead wed Andrew Quist, a wealthy but arthritic philanthropist decades her senior. Now, Sharon needs Milano’s aid again. She’ll pay him $20,000 to head off a homicide at the expansive Quist estate, the designated target—a resident there and a recipient of several threatening missives—being the aforementioned Kondracki, who has restyled himself as pontifical mystic Kalos Daskalos.

What we have in these pages is basically an Agatha Christie-style country-house whodunit, with the eccentric suspects including several “movie people” (all hoping to fund their latest project from Quist’s deep pockets) and Maggie Riley, a plucky art historian and Jack the Ripper expert, serving as Quist’s confidential secretary. A convenient blackout, Milano’s amorous attentions toward Maggie as well as Sharon, and our sleuth’s perfunctory efforts to protect the spurious sage all keep the plot moving swiftly. Yet in the end, Star Light, Star Bright is an often humorous mystery more ordinary than innovative. Had Milano not also been cast in its sequel, he might well have slipped into obscurity.

The Dark Fantastic (1983)

“Controversial” is the term most often applied to Ellin’s The Dark Fantastic. Due to the corrosively bigoted views expressed by its chief antagonist, that psychological suspense yarn was rejected not only by the author’s longtime editor at Random House, but also by “several other publishers,” recalls Otto Penzler, a prolific editor of crime-fiction anthologies and the proprietor of Manhattan’s Mysterious Bookshop. Penzler, who in 1975 had established a small publishing house called The Mysterious Press, eventually came to Ellin’s rescue. “I read [The Dark Fantastic] and thought it was a brilliant work,” he tells me, “and offered to publish it. It got an amazing, two full-column review in The Wall Street Journal, among many other good reviews. I was (and am) proud to have published this very good book by a very good writer and a very good man.”

The story follows two overlapping plotlines. In the first, we have Johnny Milano, annoyed at having just turned 40, trying to locate a couple of pricey pre-Impressionist paintings stolen from a private California collection. The owner’s insurance company figures those beachscapes are “on their way to a middleman working out of New York.” Milano, who apparently developed a keen knowledge of art while coming up in the world, suspects the intermediary is jet-setting but shady Wim Rammaert, owner of a gallery near Carnegie Hall, so he reconnoiters that showroom, sniffing for clues. In the process, our not-quite-a-hero develops a pulse-racing interest in Christine Bailey, Rammaert’s headstrong, 23-year-old African-American receptionist. Trying to get closer to her, Milano proposes that he pay Christine to help him nail Rammaert; but in exchange she wants his professional expertise rather than his lucre or lust. It seems she has a pretty mid-teens sister, Lorena, who’s recently acquired clothes with cash from an unknown source, and Christine wants assurance that those funds aren’t ill-gotten.

Here’s where the second plotline comes in. It involves that earlier-referenced bigot, one Charles Witter Kirwan. He’s a widowed, 68-year-old retired history professor, and he lives in his grandfather’s elegant Queen Anne-style Brooklyn abode, right next door to a degenerating 1920s apartment building he also owns, constructed by a subsequent Kirwan progenitor. Throughout his teaching career, Kirwan had endorsed his liberal colleagues’ support of the Big Apple’s large Black population. But after being told he has lung cancer and not so very long to live, he’s decided to strike back against the Black people (he calls them “Bulangas”) who Kirwan blames for despoiling the neighborhood his Dutch-heritage family helped found. With more than 70 sticks of dynamite at his disposal, Kirwan intends to raze his four-story apartment structure, killing himself and most of his renters. Those occupants include Lorena Bailey, who lives there with her mother and brothers.

What makes this novel difficult to read, is that Ellin alternates third-person chapters about Milano—whose pursuit of Lorena’s secrets leads him to discover Kirwan’s catastrophic scheme—with others told in first-person from the ex-educator’s perspective. The author obviously abhors Kirwan’s opinions, but is also fascinated by his character’s psychological and moral collapse. For Ellin to place himself inside the mind of that cadaverous racist over and over again confirms his commitment to expanding the detective genre’s “diversity of theme and treatment,” but it must have left him rattled after each day’s writing.

One can’t help but wonder whether, having sent Johnny Milano out on two assignments, Stanley Ellin thought him durable enough for a third adventure, or more. “As far as I know,” says Penzler, “Stan had no plans to do another Milano book, but then Stan almost never talked about his books or stories in progress.”

Sadly, Ellin penned only one more novel before dying, at age 69, in 1986.