T.E.D. Klein is perhaps best known as a horror writer’s horror writer. Writing about his short fiction in Tor.com, Anne M. Pillsworth observed, “He’s unexcelled in creating realistic milieus, the places and times his characters move through, the customs of their little countries, and he does it with a minuteness of detail some might find excessive.” But horror fiction isn’t the only thing Klein has written in his long career, and the recent nonfiction collection Providence After Dark and Other Writings points readers to another side of his work—one which resonates with contemporary nonfiction in unexpected ways.

One section of Klein’s collection is dedicated to his tenure as the editor of Crime Beat magazine in the early 1990s. With the tagline “the newsmagazine of crime,” the publication seems on first glance to be ahead of its time, given the true crime boom we’ve lived through in recent years.

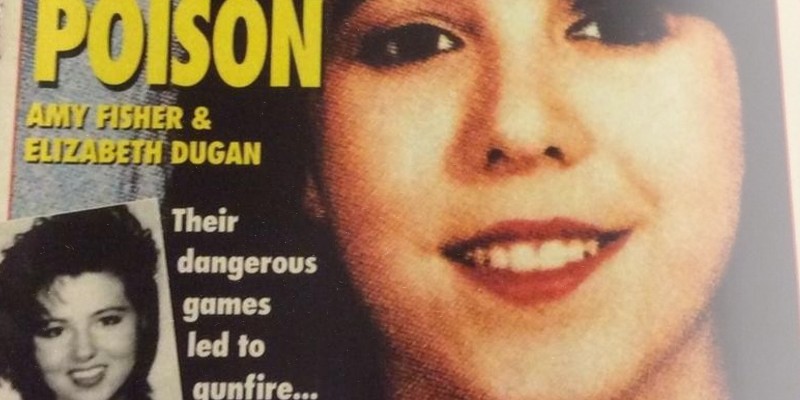

A look at some of the covers published during the magazine’s run reveals plenty that wouldn’t be out of place in a more contemporary true crime library. Crime Beat included stories on serial killer Charles Ng, the legacy of the Manson Family, and a feature on the recently-concluded trial of Aileen Wuornos. And one cover story, an analysis of why John Gotti remained wildly popular while Leona Helmsley was vilified, the kind of meta-media subject that’s only grown in popularity in recent years.

But some of the other headlines take a more sensationalistic and reactionary perspective. A headline on the May 1992 Crime Beat trumpets the story of “How The Courts Made a Mugger a Millionaire.” The October 1991 issue featured a ridealong with COPS. And the April 1992 issue featured a particularly alarming headline: “Pampered Prisoners: What Do They Cost You?”

While the larger sociopolitical context of the true crime boom has been up for debate for a few years now, 2020 has intensified those discussions. Writing at NiemenLab in June, Nicholas Quah pondered the question of whether true crime podcasts make the justice system seem better than it actually is. In a Vanity Fair article a month later, Marisa Meltzer explored similar questions in depth. In writing about podcasts, Meltzer gets at a much broader question with respect to true crime in general:

“Protests and the movement to defund the police have made it increasingly difficult to ignore the paternalistic and trusting relationship between many of my favorite podcasts and the criminal justice system, a relationship that betrays my understanding of the world: that justice isn’t actually blind, that there’s an inherent fallacy in the idea of bad guys, and that punishments often don’t fit the crimes.”

To an extent, that also raises the question of who is fascinated by true crime stories, and why. For some, it’s about the idea of seeing law enforcement acting like heroic archetypes, working tirelessly to capture those who have done wrong. For others, it’s about the ambiguity of the judicial system, and of the ways it can be applied incorrectly or maliciously. True crime is a genre broad enough to encompass a wide spectrum of ideologies, which can lead to a few dissonant moments when taking in a large survey of the form.

Klein describes his own politics as conservative, and something of this worldview crops up in the section of his own writing for Crime Beat that were collected in Providence After Dark. (It’s worth mentioning that this is the most ideological the book gets, by and large.) In an October 1991 essay from early in the magazine’s run, Klein makes the case for why a magazine should cover true crime:

“It’s also the fascination of conflict, of struggle—the essence of every great plot. And it’s a conflict in which we can all too easily imagine ourselves. For while few of us are criminals, most of us are—or will be—crime victims. The same is true of friends or loved ones: We’re all potential victims today.”

This emphasis on victimhood is a theme Klein returns to again and again—including in one piece from the winter of 1991 critical of the current parole system. This was a theme Klein revisited several times, if the collected writings here are any indication. “Not all parolees turn to murder, like the ones you’ll see chronicled in this issue,” Klein wrote in November 1992. “But chances are good that they’ll leave the world a little worse for their presence.”

A 1991 Entertainment Weekly article on the launch of Crime Beat offered a sense of the ideological range found within. The article notes that the debut issue “includes a critique of the American prison system, an analysis of the professional expertise of the lawyers on L.A. Law, a profile of lawyer-turned-novelist Andrew Vachss (Hard Candy, Strega), and an article on home security.”

Crime Beat’s time on newsstands wasn’t long: it debuted in late 1991 and ran until early 1993 before running out of money. In his commentary on his own contributions, Klein notes that the publication “had not been snapped up, as we’d privately hoped, by some major publisher.” It’s a lot harder to imagine a true crime-themed publication having difficulty finding an audience today, though it’s likely that the editorial voice would look very different. People are drawn to true crime for very different reasons, and finding a balance between the ideological poles of true crime fans in 2020 may be an impossible task.