Crime writers setting their stories in the Victorian era are privileged to have a vast range of sources to consult about the social history, politics and crimes of the time. In Britain, where my Arrowood novels are set, newspapers carried lengthy court reports (often with verbatim transcripts), true crime papers such as the Illustrated Police News were popular, and real crimes frequently made their way into the growing body of realist literature. As Judith Flanders describes in her book The Invention of Murder, Industries grew up to service the public’s appetite for the more gruesome murders of the day. Balladeers sold songs about famous killings, pamphlets full of speculation and gory details were hawked on street corners, guides ran tours of the murder sites, and theaters put on plays based on real police investigations. At the same time, journalists and researchers such as Jack London, Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew journeyed into the underworld to report on what they found.

These sources reveal a brutal world in which the struggle for survival, the harsh consequences of breaking moral taboos, and the lack of a social net led many to adopt creative and sometimes cruel ways to get by. Here are just a few of the unusual crimes of the Victorian underworld.

Stealing people’s clothes

Nowadays, a thief would be more likely to go for a cellphone or a laptop, but in the 1800s clothes might have been the most valuable things many people possessed. There were street markets given over to selling used garments, often still filthy from their last owners, and the courts were full of people being prosecuted for stealing an overcoat, a pair of boots, or a pair of stockings. Thieves would steal clothes by harvesting them from washing lines (‘snowing’), breaking into a person’s home, or through highway robbery. Gangs would pounce on washerwomen taking clothes to drying grounds and steal their laundry baskets. The most interesting were the ‘skinners’, kindly women who lured well-dressed children into an alley, then proceeded to strip them of their clothes and boots before sending them off in just their underwear.

Selling body parts as food

Nowadays we know of criminal organizations that sell human organs for transplant, but in the Victorian era there was a more gruesome equivalent. Most of us know the famous Victorian story of Sweeney Todd, the London barber with a penchant for killing his customers. Once despatched, his friend Mrs Lovett made meat pies out of them to sell in her pudding shop. Although some claim this is a true story, there isn’t a lot of evidence Todd ever existed. However, there is a similarly gruesome story from London which is true. In 1879, Kate Webster was fired from her post as servant to a Mrs Thomas. In revenge, she killed her mistress with an axe to the skull, sliced her body to pieces, and boiled it up in a large pot. She then burnt the bones and meat, but kept the body fat which she sold as ‘best dripping.’ Beef dripping was a popular food in Victorian time, used to fry foods or just spread straight onto a nice piece of bread.

Baby farming

In the days when it was considered a disgrace to have a child out of wedlock, young unmarried mothers, or widowed fathers, would often pay an older woman to raise the child. In many cases, the mother or father would have no more contact, and it was this that allowed some terrible crimes to be committed by evil ‘baby farmers’. In the 1860s, the ‘Brixton baby-farmers’ Margaret Waters and Sarah Ellis killed at least 19 infants in their care through starvation. To make the hungry babies more manageable, they were given laudanum, a freely-available opium tincture. Perhaps the most notorious baby-farmer was Ameila Dyer, executed in 1896. She killed her charges either through starvation or strangulation with fabric tape, the bodies being dumped in a canal. We don’t know exactly how many babies she killed, but historians estimate that over the twenty years of her career it could have been as many as fifty. When asked how to identify her victims, she said ‘You’ll know mine by the tape around their necks’.

Conspiring to have family members committed to asylums

As Sarah Wise describes in her book Inconvenient People, there were a good number of cases where people were committed to ‘lunatic asylums’ by their nearest and dearest for entirely selfish reasons. Since diagnostic systems for mental illness were at an early stage of development, and there was no consensus over what and was not evidence of ‘lunacy’, doctors were able to argue that people who were eccentric in some way (rather than clearly ill) should be committed to an asylum, losing control of their affairs in the process. This gave an opportunity for unscrupulous relatives to gain control of the unfortunate person’s money. Some of these cases were taken to court and reported widely, with rival doctors arguing over whether the person was ‘mad’ or simply eccentric. But it wasn’t just for the sake of money. Edith Lanchester was a young feminist who decided to live with her lover without getting married. Her family found this intolerable, and, in 1895, her father and two brothers captured her and had her locked an asylum in Roehampton. This was endorsed by a Dr Burrows, who declared that Miss Lanchester’s decision equated to a threat of committing ‘social suicide’ and was therefore evidence of irrationality. He diagnosed her as was suffering from a specific ‘monomania’ related to her attitudes to marriage. Lucky for her, the Lunacy Commissioners came to inspect the asylum two days later and freed her.

Impersonation of family members

Nowadays, most identity fraud is committed online, but, before the days of DNA testing, there was a brand of fraud where people turned up in person claiming to be a lost family member in order to inherit the family wealth. Arthur Orton, known as the Tichborne Claimant, was one of the most audacious. When her son, Sir Roger Tichbourne, was lost at sea, the wealthy Lady Tichborne put adverts in papers around the world searching for him. Orten, a butcher’s son, wrote from Australia claiming to be him and asking for her to send him money. She did, but also pleaded with him to come home. He decided to give it a go, and, when he arrived, the old woman welcomed him as her lost son even though Orten didn’t have Sir Roger’s posh accent and weighed 170 kg compared to her son’s 57kg. When he began to claim the family estates, other relatives took legal action. The case took four years to come to court, during which time Lady Tichborne continued to believe he was her son. She died just before the case was heard, meaning he lost his most valuable witness. Nevertheless, he memorised an enormous amount of facts about Sir Roger’s life and managed to convince 100 people to vouch for his identity. The case lasted 1,025 days, and in 1874 he was convicted and sentenced to fourteen years hard labour. During his prison years, he insisted on being addressed as Lord Tichborne, and would not respond to the name Orton.

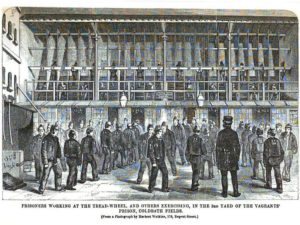

Victorian punishments

Convicted criminals were sentenced to fines, imprisonment (with or without hard labor), flogging, transportation to the colonies, or death. In prison, hard labor involved a range of unpleasant and useless tasks. Picking oakum involved prisoners sitting all day unravelling thick, tarry ship ropes, which caused bleeding fingers and ruined nails, a particular torment to Oscar Wilde in his time in Reading Gaol. The crank was a box with a ratcheted handle that had to be wound for hours on end, while the tread (or ‘cock-chafer’) was a giant wheel with foot-treads in step formation. Prisoners had to make the wheel turn for hours on end by climbing the moving steps. Other forms of hard labour included making prisoners break rocks or lift and move cannon-balls back and forth across a courtyard all day.

Harsh punishments were often given out for relatively minor offenses. For example, in 1888, George Thurgood left the workhouse (which housed homeless paupers) to look for a job. He was picked up and taken to the magistrates and sentenced to 15 days hard labour for ‘searching for work in workhouse clothes’. In 1871, 14-year-old Isaac Davies was sentenced to three months with hard labour for stealing 20 oranges and a packet of nuts. Hard times indeed.