There’s a scene in Clint Eastwood’s 1992 film Unforgiven where a kid named Schofield has just killed a man for the first time, and he’s obviously distraught. He’s trying to rationalize what he’s just done, and how this man will never walk or breathe or love again. Finally, he takes a swig of booze and mutters, “Yeah, well, I guess they had it coming.” Clint Eastwood’s character, Will Munny, stares off in the distance and says, more to himself than the kid, “We all got it coming, kid.” It’s a poignant line and is a response to the moralistic good vs. evil westerns that dominated the early days of film to a more cynical and complicated world view. More than providing history lessons, the western, like horror and science fiction, has always been a vehicle to express the fears and moral uncertainties that face our nation. And in recent years, as we have been more and more consumed by a sense of increasing violence and pervading doom, it is no wonder that the western has turned darker and more violent, as much gothic as western.

The west has always represented the American mythos, a wide-open land of freedom and possibility. But freedom can easily transform to loneliness, and those wide-open spaces can transform to isolation. In Terrance Mallick’s 1973 film, Badlands, you have dramatic juxtapositions between the beautiful landscapes of the west and the senseless violence delivered by the people within those landscapes, namely Kit (played by Martin Sheen). Near the end of the film, after having killed seven people, including his lover’s father, Kit records a message. In part, he says, “Nobody’s coming out of this thing happy. Especially not us. I can’t deny we’ve had fun though.” It’s a chilling final line, and one that illustrates the growing sense of nihilism in America, a far cry from the white hat-wearing protagonists of early westerns. Equally chilling is the role of Holly, played by Sissy Spacek. Holly is enamored with Kit, who comes across as a psychopathic James Dean. She’s the (innocent?) bystander as Kit goes on his rampage. Instead of being horrified, she seems mostly indifferent, commenting how “I didn’t feel shame or fear, but just kind of blah, like when you’re sitting there and all the water’s run out of the bathtub.” In many ways, Holly represents the ethos of America. We stand by and watch all of the violence on our televisions and are no longer able to muster rage, only an ambiguous feeling of “blah.”

Nearly a decade after the release of Badlands, Bruce Springsteen released the album Nebraska. It was a stunning departure for the rock star, especially considering that his next album would be the bombastic Born in the USA. He recorded the songs on a 4-track recorder, carried the cassette in his pocket for weeks, before finally deciding to release the album as is. The entire album is filled with dread, narratives of isolation and violence, and no song better illustrates this dread than the title song, a retelling of Mallick’s Badlands, which itself was inspired by the real-life murder spree of Charles Starkweather. In a somber voice, Springsteen ends the song with this chilling line: “They wanted to know why I did what I did. Sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” But Springsteen wasn’t the only singer one using the west as a setting for carnage. Artists like Tom Waits, Johnny Cash, Steve Earle, The Handsome Family, and even cheese balladeer Richard Marx (listen to his surprisingly dark track “Hazard,” which also takes place in Nebraska) wrote songs that could be credibly classified as Western Gothic. Like the genre of gothic or the subgenre of southern gothic, western gothic is as much about a feeling or an aesthetic as it is about a set of definitions. Music is capable of providing this feeling more than all of the other arts. Take the soundtrack of Paris, Texas by Ry Cooder. Although there are no chilling lyrics, Cooder presents a stark landscape with his somber guitar and eerie background noise. Here the Promised Land isn’t anything to search for, it’s something to be avoided at all costs.

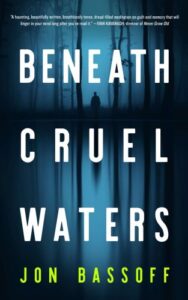

Here the Promised Land isn’t anything to search for, it’s something to be avoided at all costs.While gothic fiction uses decaying settings, claustrophobic atmospheres, and the possibility of the supernatural, and western fiction relies on beautiful vistas and good men pushed to the limits by black hats or the brutality of an indifferent nature, western gothic fiction combines those elements, holding hostage the beautiful settings and creating a tableau of something more foreboding. As far as I can tell, the first novel to make mention of western gothic is Richard Brautigan’s absurd tale, The Hawkline Monster, which even uses “Gothic Western” in its subtitle. This is more of a parody novel, poking fun at westerns and gothics, but some of the tropes are there, namely the amoral gunmen, a character that would be expanded upon in Stephen King’s novel, The Gunslinger. The opening line of King’s novel is iconic, perfect in its simplicity: “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.” But for a western novel to be truly gothic, we need more than starkness and loneliness; we need more than a morally ambivalent antihero. We need a sense of the grotesque. I would argue that, in this case, Cormac McCarthy is the master of the western gothic. Novels like Blood Meridian and The Road combine this western aesthetic with something truly terrifying. Sometimes McCarthy’s lyricism distracts us from the grotesqueness of his vision. In Blood Meridian, he writes, “…all the horsemen’s faces gaudy and grotesque with daubings like a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious, all howling in a barbarous tongue and riding down upon them like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of Christian reckoning, screeching and yammering and clothed in smoke like those vaporous beings in regions beyond right knowing where the eye wanders and the lip jerks and drools.” Throughout the novel, McCarthy forces us to reckon with the realities of the Old West, realities that include blood-soaked scalps, dead infants, and severed body parts. Other of his novels, namely The Road and No Country for Old Men, continue with this brutality within the setting of the west, but they don’t quite match the pure grotesquerie of Blood Meridian.

Of course, no discussion of the western gothic would be complete without mentioning the roles of Indigenous writers on the landscape. Contemporary novelists such as Stephen Graham Jones, Erika Wurth, David Heska Wanbli Weiden, and Eden Robinson have used the vast setting of the American (and Canadian) west to explore Indigenous themes such as identity, representation, and trauma. In Robinson’s Monkey Beach, for example, she utilizes many tropes of the gothic including a descent into madness. However, while in the western gothic visions of demons and the supernatural are often symbolic for mental illness, in Robinson’s novel, and in much of Indigenous fiction, these visions can be a sign of healing. Wurth also brings an Indigenous sensibility toward the gothic in her novel White Horse. Wurth’s protagonist, Kari, is gifted an ancient bracelet, and this bracelet turns out to be a portal of past traumas. And while these traumas are personal, it’s hard not to extend beyond her personal experiences to the never-ending horrors that Indigenous people have faced in our nation’s bloody history. But, as in Robinson’s novel, in White Horse the revealing of the supernatural also leads to a type of spiritual healing, a healing that is not usually evident in the western gothic.

America is a country steeped in violence as much as the mythos of freedom and self-determination. And while we might be tempted to follow Horace Greeley’s advice and “Go west, young man,” artists are here to remind us of the monsters—usually in human form—that lay wait across the plains and mountains and deserts.

***