The house located at 12 Gay Street in New York City’s Greenwich Village is haunted. It’s famously haunted. For decades now, ghosts have been seen on its staircases and heard through its walls. Frank Parris (the marionettist responsible for the original Howdy Doody act) resided there at one point, and he reported seeing three different phantoms inside, including a suave male spirit wearing a top hat and cape. This figure in formal wear is the most commonly spotted of all the ghosts at Number 12, most often seen peering out of windows. It’s speculated that he might be the ghost of Jimmy Walker, who served as the mayor of New York City from 1926 to 1932—because Walker bought the home as a present for his mistress, a Ziegfeld girl named Betty Compton whom he later married. And before that, during the ’20s, 12 Gay Street housed a speakeasy—rounding out a raucous, bustling history that gives way to its current reputation as a den of paranormal activity. An erstwhile stop on New York City’s West Village ghost tour, it is studied by experts, approached by visitors, and avoided by locals. “It’s legendary,” one neighbor told New York Magazine in 2009, “that ghosts live there.”

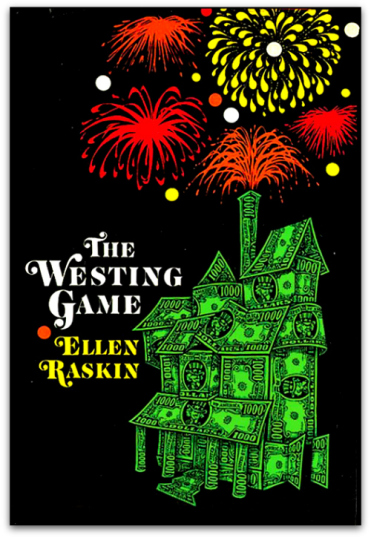

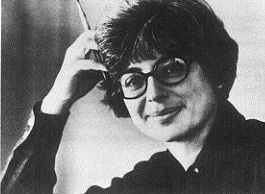

But the house at 12 Gay Street is also the site of another remarkable feat of immortality, with a less well-known connection. It was there that the children’s book author and illustrator Ellen Raskin, who had purchased it with her husband in the early 1970s, wrote her masterpiece, The Westing Game. A patriotically-themed murder mystery about a mysterious inheritance, she began it in 1976 (the year of the bicentennial). When it was published two years later, it won the Newbury Award. It remains one of greatest and most beloved children’s novels of all time.

At first glance, The Westing Game appears to be a classic whodunit. Its plot revolves around the death of a mysterious industrialist named Samuel W. Westing, whose demise brings sixteen diverse people to his mansion for the reading of his will. These people—who would be strangers, except that they just have just been sold units in the same, brand-new apartment complex on the Lake Michigan shore in Wisconsin—are broken into pairs and informed that they must compete with the other groups to solve the mystery of Westing’s murder. If they do, they will inherit his entire $200 million fortune. They are given sets of clues (jumbled, seemingly-nonsensical phrases) that the dead man prepared himself, and as they search for meaning, they wind up exploring different facets of Westing’s legacy, reanimating a stranger who ironically seems to know them all very well. The motivations of the heirs shift throughout the course of the book as unlikely friendships are formed and broken bonds are repaired, but its central protagonist, a thirteen-year-old girl named Turtle, stays more focused on the prize than anyone else, outsmarting the flamboyant puppet-master Westing who has been managing, somehow, to pull the strings from beyond the grave.

At first glance, The Westing Game appears to be a classic whodunit. Its plot revolves around the death of a mysterious industrialist named Samuel W. Westing, whose demise brings sixteen diverse people to his mansion for the reading of his will. These people—who would be strangers, except that they just have just been sold units in the same, brand-new apartment complex on the Lake Michigan shore in Wisconsin—are broken into pairs and informed that they must compete with the other groups to solve the mystery of Westing’s murder. If they do, they will inherit his entire $200 million fortune. They are given sets of clues (jumbled, seemingly-nonsensical phrases) that the dead man prepared himself, and as they search for meaning, they wind up exploring different facets of Westing’s legacy, reanimating a stranger who ironically seems to know them all very well. The motivations of the heirs shift throughout the course of the book as unlikely friendships are formed and broken bonds are repaired, but its central protagonist, a thirteen-year-old girl named Turtle, stays more focused on the prize than anyone else, outsmarting the flamboyant puppet-master Westing who has been managing, somehow, to pull the strings from beyond the grave.

Knowing now that Raskin wrote this novel in the possible presence of ghosts casts the book I’ve loved for many years in a different light. The Westing Game is, famously, a limitless, multitudinous story (I have read it numerous times in the last fifteen or so years, and I’m always impressed at new angles I discover, new meanings behind the clues I’ve read tens of times before). Last year, in The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino wrote about how The Westing Game satirizes capitalism in America, analyzing the deceased figurehead in the vein of another (real) Wisconsin immigrant-turned-industrialist, John Michael Kohler, whose belief in the American Dream was his undoing. She also reads the novel as a commentary on the death of Howard Hughes, whose own passing in 1976 (the year Raskin began writing the novel) brought about a will contestation that shocked the nation, with a fraudulent heir making a play for a chunk of his fortune.

In 2018, Columbia University English professor and Co-Editor-in-Chief of Public Books Nicholas Dames analyzed another facet, writing for that publication about The Westing Game’s complex experiments with form—packed full of riddles and puzzles, it is a novel that you must play, a game that you must read. But it’s so much more, too. It folds and unfolds its stories, rearranges the alliances and alignment of its sixteen main characters, rather like a Rubik’s Cube. Containing multitudes, it can become an entirely new thing, when looked at from a new angle. It is a murder mystery, a tribute to American labor history, a farcical indictment of capitalism, a book of riddles, a large-scale family drama, a bildungsroman, etc. And it is also, in its way, a ghost story. But not a kind of ghost story you’ve ever read before.

I feel I must note that reading The Westing Game as a ghost story had not occurred to me until I did a little digging into the stories of specters which, according to popular Greenwich Village mythology, congregated in Raskin’s own home. In my research, I’ve come upon many accounts of the myriad phantasmagoria all stirred up at 12 Gay Street; I’m happy to report that these clues suggest such a curious, motley assemblage of neighbors that they might very well be characters in Raskin’s own novel, gathered around a table in Samuel W. Westing’s library, waiting on directions from the beyond. But the history of the metaphysical hoopla at 12 Gay Street does a bit more than outfit Raskin’s novel with coincidental, kindred spirits. It reminds us that just as The Westing Game is about lives, it is also very much about afterlives. It is, to put it simply, a novel very much about death.

For a moment, this seems like a classic, Christie-esque murder-mystery move: making the inciting death a jumping-off-point and excuse for puzzle-solving rather than a mournful or tragic event. There are no literal ghosts in The Westing Game, but the novel’s events begin with a more traditional ghost story, told on Halloween. Sandy McSouthers, the chatty, middle-aged doorman at Sunset Towers, and an elderly courier named Otis Amber, recount to the three teenagers gathered outside (Turtle Wexler, Doug Hoo, and Theo Theodorakis) a yarn about an incident that happened in the mansion a few Halloweens before—when two unfortunate kids broke in and saw something so horrible that they ran out screaming. One ran until he fell off a cliff, while the other—whose hands were dripping with blood, went into shock. All he says now, Sandy and Otis tell the kids, is the phrase “purple waves,” which he repeats over and over in the state asylum where he now resides.

This incident, which reads as the stuff of campfire legend, functions as a kind of bait-and-switch. The Westing Game’s spectral suggestions promise ghosts and hauntings but yield a concept less supernatural but more real: legacy, which is the impact of a life, rather than the lingering of one beyond death. Sandy and Otis’ tale suggests a ghostly legacy for Samuel W. Westing and casts a bleak shadow over the man who will soon become so central to the characters’ lives, dangling monetary bait over heirs who, more often than not, never met him. Who was he really? The heirs will do some research into his life a bit later, but they’ll find a tragic story of a man who believed he was building a company that would promote the American dream, but one which was actually full of strikes, layoffs, and lawsuits. His daughter committed suicide the night before her wedding, his wife deteriorated from grief. The heirs who do remember him (particularly Judge J.J. Ford, a high-ranking Black female justice of the peace whom Westing had once put through school) think of him as mean, cruel, and competitive.

Just as The Westing Game is about lives, it is also very much about afterlives.When we do meet Westing’s ghost, in a sense, through his will reading, we’re presented with a different figure, one so desperate for a new legacy that he rounds up a group of tangentially-related people who might still be able to remember him differently. This section of the novel reinforces the great existential questions which govern the novel: How will we be remembered when we die? Who will we entrust with the things we worked hard in our lives to achieve? Who will want to know us as we grow old, and why? Westing’s heirs are strangers because he has no family. After all, his body is found by a trespassing preteen. All the money in Samuel Westing’s bank account isn’t worth much, compared to what everyone wins by playing the game: a family. Ultimately, he gives them all the one thing he never had.

Westing’s assemblage of descendants would feel random, except that they’ve all just become neighbors. He has deliberately chosen them, architecting this whole scenario just for them. The first chapter begins with the renting of the apartments in Sunset Towers to “the people whose names were already printed on the mailboxes in an alcove off the lobby.” They are all ages, all races, all economic backgrounds—they know about no greater apparent connection to the dead man than to each other. They all, also, have their secrets. At the end of the chapter, the narrator asks:

Who were these people, these specially selected tenants? They were mothers and fathers and children. A dressmaker, a secretary, an inventor, a doctor, a judge. And, oh yes, one was a bookie, one was a burglar, one was a bomber, and one was a mistake.

The reader is charged with figuring out who these people really are—literally and figuratively. Westing already knows. He picks people who, like him, need some sort of chance taken on them—a shot at redemption or reinvention, or an opportunity to discover who they truly are. With his afterlife, he offers his heirs second acts to their own. Across the board, they use this opportunity to build things: businesses, partnerships, relationships, careers, fame, influence. He gives them all something to inherit, which they all turn into things they can pass down.

Despite the large ensemble, Westing remains the specter at the center of the novel—frequently a metaphor, possessing a posthumous omnipotence and control that is difficult to explain. Westing had been obsessed with chess in his lifetime, and now these players are his pawns. His long history becomes the key to unraveling the mystery at hand, and into whose history their own stories become absorbed. By playing it, they allow themselves to be haunted by him, all he represents, and the second chance he wishes he once had. Turtle, who ultimately wins the game, does so by figuring out that Westing has more players on the board than it might have initially seemed. She refuses to play by his outlined rules and solves the case, becoming his successor. And by the end of The Westing Game, fully having inherited Westing’s legacy (including having garnered a seat on the board of Westing’s company), the now-adult Turtle picks a successor of her own, continuing the Westing tradition.

***

For a novel so much about legacy, the life of the creator behind The Westing Game is less well-known. Who was Ellen Raskin, the great mind behind this scintillating book? When I first read The Westing Game, it was after Puffin had put out a 25-year anniversary edition, which it did in 2003. I knew nothing about Raskin, but I read about her before I read the novel, from her editor Ann Durell’s sentimental, three-page introduction. I learned that Raskin had not written a single novel until 1970 (when she was forty-two). Before that, she had written a handful of picture books, but mostly worked as an illustrator, designing more than 1,000 book covers throughout the course of her career (including for A Wrinkle in Time).

Durell provides a slight biographical sketch: born in Milwaukee just before the stock market crash, Raskin’s childhood was one large road trip, in which her whole family drove from Wisconsin to California while her father looked for work. Later, in New York in 1960, she married Dennis Flanagan, the longtime editor of Scientific American, with whom she had a daughter, Susan. She was “a financial wizard,” who (like her heroine Turtle) made a fortune by playing the stock market. She loved gardening in the large vegetable patch of her Long Island cottage. She loved the compositions of Franz Schubert, particularly the quartet “Death and the Maiden.” She was a musician. She was a poet. She was a smoker.

In life, you’re either a devotee of The Westing Game, or you’ve never heard of it. Same goes for Raskin, same goes for any of her other books. I stumbled onto this paradox while reading Durell’s introduction; I noticed that she treats Raskin as someone whose legacy everyone would know. At one point, she calls a line in one of Raskin’s other books “immortal,” but I had never heard it uttered before. The book referred to is Raskin’s first novel, an oddity called The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon (I Mean Noel). The Westing Game was Raskin’s fourth and last of the novels she’d write. It wasn’t her first dense literary reflection on community and legacy. It also wasn’t even her first hack at the sprawling, vaguely-supernatural, riddle-addled super-mystery genre that The Westing Game came to be—a genre she called, in the novel’s introduction, “a puzzle-mystery.” No, The Westing Game was simply the novel in which she perfected weaving together all these threads, and therefore, the one which is best remembered.

In life, you’re either a devotee of The Westing Game, or you’ve never heard of it. Same goes for Raskin, same goes for any of her other books. I stumbled onto this paradox while reading Durell’s introduction; I noticed that she treats Raskin as someone whose legacy everyone would know. At one point, she calls a line in one of Raskin’s other books “immortal,” but I had never heard it uttered before. The book referred to is Raskin’s first novel, an oddity called The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon (I Mean Noel). The Westing Game was Raskin’s fourth and last of the novels she’d write. It wasn’t her first dense literary reflection on community and legacy. It also wasn’t even her first hack at the sprawling, vaguely-supernatural, riddle-addled super-mystery genre that The Westing Game came to be—a genre she called, in the novel’s introduction, “a puzzle-mystery.” No, The Westing Game was simply the novel in which she perfected weaving together all these threads, and therefore, the one which is best remembered.

While you’ll surely encounter The Westing Game at some point, you probably won’t encounter its three obscure predecessors. Rather like The Westing Game, all these stories are cockamamie tales of riddles and clues, all distracting from a big existential question. All these stories are about death. They’re about what to do when someone we love leaves us, about the new relationships we make in the wake of another loss, about the stories that loved ones will tell about us when we’re gone. They’re all ghost stories, in a way.

The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon (I Mean Noel) was published in 1971. It tells the story of a canned soup heiress named Mrs. Caroline “Little Dumpling” Fish Carillion whose family has perished in a soup factory explosion, and who goes in search of her husband Leon (or, as he prefers, “Noel”), whom she married at age five (he was seven), and reunited with at age nineteen, only to lose him in a boating accident. He’s not dead, though, just missing—and he’s left her clues to find him, clues that take her decades to solve and bring her all over the country. Figgs and Phantoms followed in 1974, and was a Newbury Honor Book; that story is about Mona Lisa Figg Newton, a teenager with an eccentric family who attempts to follow a set of clues left by the only relative she likes, an eccentric book dealer named Uncle Florence, after he dies. He’s explained that he’s bound for a secret family paradise, and Mona Lisa is determined to figure out where that is.

Raskin’s penultimate novel is her darkest of the four: a Sherlock Holmes homage called The Tattooed Potato and Other Clues, published in 1975, and about a young woman named Dickory Dock who becomes apprenticed to an enigmatic portraitist known as Garson, and winds up his accomplice in various schemes. Bleak but still goofy (Dickory’s parents died in a tragic double-murder but there is also a character named “Shrimps Marinara”), it is mostly about the ragtag and often incognito characters who clandestinely rendezvous inside Garson’s Greenwich Village brownstone. Durell notes that the crowded townhouse setting for this story is, in fact, Raskin’s own brownstone, though she changes the address to 12 Cobble Lane. But it is the same house—she describes it, detail for detail, right down to the skylit attic studio where she wrote and illustrated all her projects.

These three novels are The Westing Game’s own kooky relatives, restless spirits that call it to mind without reproducing it perfectly. But they’re also formal experiments in legacy-formation and remembrance. Raskin rewrote moments from her own life as these novels, practicing a kind of complex endowment not dissimilar to Westing’s—for instance, the cross-country trip taken by Mrs. Carillion is a retelling of her own family’s Depression-era migration. So, in reading these four books, you play Raskin’s game, solving puzzles and clues that seem to reflect back on her. You have no choice but to remember her as you read (or play) along.

***

I learned the address of Ellen Raskin’s Greenwich Village brownstone from Ann Durell’s introduction. In retrospect, I suppose Durell’s inclusion of this detail was a highly unusual feature, because in 2003, when this edition was published, Raskin’s husband Dennis Flanagan still owned the house with his second wife, the literary agent Barbara Grossman Williams, whom he married in 1999. I wanted to ask Durell about this detail, but when attempting to contact her, I discovered that she had passed away in 2018. Flanagan died in 2005, leaving his widow to sell the home.

Ellen Raskin herself had died in 1984 (only five years after the publication of The Westing Game). She suffered a disease of the connective tissue, which Durell notes caused her periods of great pain. She died in the hospital, but her memorial was held at 12 Gay Street, in her attic studio, under the skylight. Her husband hired a string quartet to play Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” for an audience of family and friends.

When researching the history of her brownstone, I was surprised that its status as the site of The Westing Game authorship did not award 12 Gay Street some sort of plaque on its façade. Of all the ghost stories born in Number 12, surely The Westing Game is the finest. I don’t know if Raskin’s spirit is one of the many who apparently gather there, now, but I’d like to think that it is—like her mid-century industrialist phantom, I imagine that she would appreciate watching generations of readers inherit The Westing Game, remembering a story about remembering.

Whatever else it is, The Westing Game is about the figures that haunt us, that are haunted themselves by the idea of not haunting us. Its ghost is not traditional, but he wants to be remembered. Samuel Westing may be dead, but there are many ways to keep him alive. Death, itself, is not the horror show promised by the novel’s meta-ghost story. It’s not even permanent; there is almost always a way to reanimate the dead. It’s just never the way you’d expect.