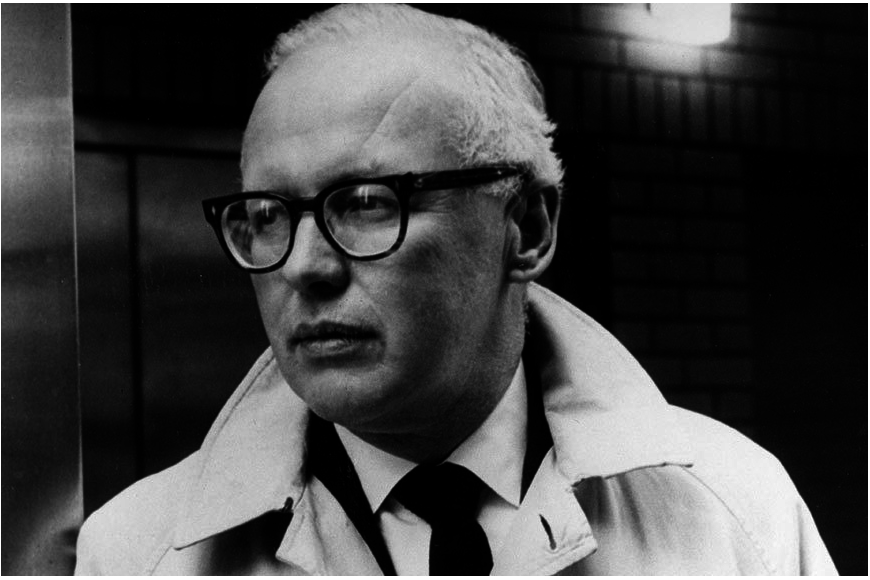

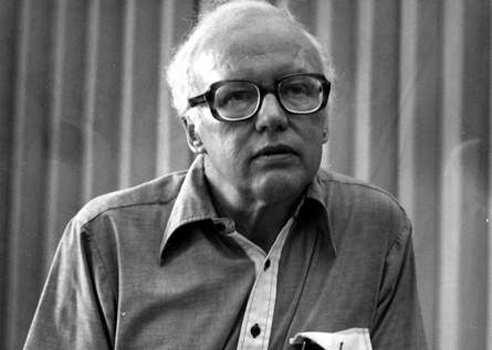

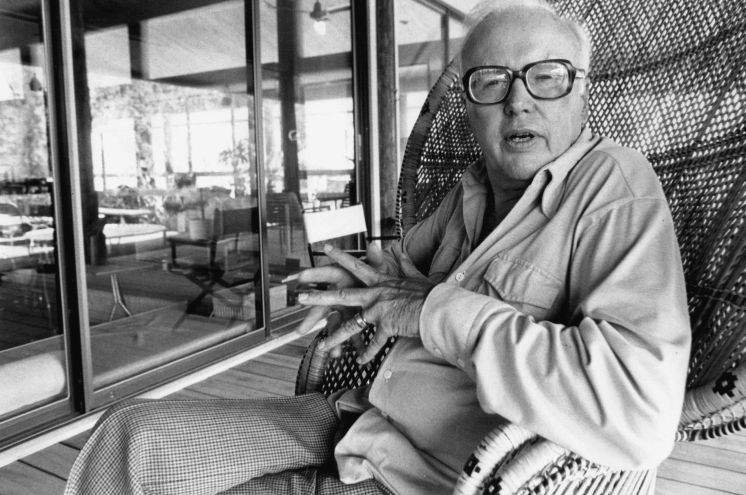

John D. MacDonald—born on July 24th, 1916—saw some things in his time. By the age of thirty, MacDonald had attended college, worked in New York City, earned an MBA from Harvard, seen action in the China Burma India Theater during WWII, joined the OSS (the CIA’s predecessor), risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel, received his discharge from the military, moved to Florida, and launched into his writing career. He was, in nearly all facets of life, prolific. Before it was all over, he’d have published more than 60 novels and 500 short stories, written under various names and ranging from westerns to sci-fi adventures to crime classics like The Executioners and, most famously, the twenty-one novels starring Travis McGee. McGee was the author’s most famous creation: the “salvage” man, the knight errant, dissipated resident of a houseboat, The Busted Flush, docked in Florida’s Intracoastal Waterway, where many a troubled soul came looking for help from good ol’ Trav. He was the quintessential Swingin’ Sixties PI: sexualized (overly, some might argue), intoxicated (ditto), checked out of mainstream society but upholding a very specific code that favored the little guy. Donald E. Westlake said of him: “Travis McGee is the last of the great knights-errant: honorable, sensual, skillful, and tough. I canít think of anyone who has replaced him. I canít think of anyone who would dare.”

Some of the social and political views embodied in MacDonald’s novels may now be out of date, but it’s hard to deny the insight and the poetry of the collected works. JDM ranks among the very finest writers ever to try his hand at crime. Reading through his works today, there’s still a great deal of wisdom to be found and more than a little wit. To celebrate the 102nd anniversary of his birth, we’ve collected here a few choice gems. So, here it is: John D. MacDonald on life, morality, the craft of writing, the art of storytelling, the futility of workaday employment, and so much more.

What drives a reader:

“The reader always wants to know what happens next, whether he’s reading The Brothers Karamazov, David Copperfield or Hemingway. If what happens next is purely physical, then you’ve got Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer shooting his initials in somebody’s midsection. If what happens is spiritual, maybe you’re reading biblical chapters to find out what happened with Moses and the Red Sea. If it’s intellectual, you’re reading to find out maybe whether they are going to discover a cure for herpes. What happens next is the thing that keeps people reading, and the more important the next [thing is], then the more important the work is.”

—May 5, 1985, Family Weekly, discovered and transcribed by Steve Scott, of The Trap of Solid Gold

A word of discouragement to young writers:

“Most beginners think that writing is a quick ticket to some kind of celebrity status, to broads and talk shows. Those with that shallow motivation can forget it. Here’s how it goes. Take a person 25 years old. If that person has not read a minimum of three books a week since he or she was ten years old, or 2,340 books—comic books not counted—and if he or she is not still reading at that pace or preferably, at a greater pace, then forget it. If he or she is not willing to commit one million words to paper—ten medium-long novels—without much hope of ever selling one word, in the process of learning this trade, then forget it. And if he or she can be discouraged by anyone in this world from continuing to write, write, write—then forget it.”

—1994, The Basics of Writing & Selling Mystery & Suspense (Writer’s Digest Guide, Vol 10), re-discovered and transcribed by D.R. Martin of Travis McGee and Me

Rainy days, and the basics of storytelling:

“The writer is like a person trying to entertain a listless child on a rainy afternoon. You set up a card table, and you lay out pieces of cardboard, construction paper, scissors, paste, crayons. You draw a rectangle and you construct a very colorful little fowl and stick it in the foreground, and you say, ‘This is a chicken.’ You cut out a red square and put it in the background and say, ‘This is a barn.’ You construct a bright yellow truck and put it in the background on the other side of the frame and say, ‘This is a speeding truck. Is the chicken going to get out of the way in time? Now you finish the picture.’”

—John D. MacDonald, The Writer (1974)

Describe, don’t evaluate:

“The most instructive thing you can do is to go back over past work, published or unpublished, and find the places where you described something at length, in an effort to make it unique and special, but somehow you did not bring it off. (I do this with my own work oftener than you might suppose.) Now take out the subjective words. For example, I did not label the air conditioner as old, or noisy, or battered, or cheap. Those are evaluations the reader should make. Tell how a thing looks, not your evaluation of what it is from the way it looks. Do not say a man looks seedy. That is a judgment, not a description. All over the world, millions of men look seedy, each one in his own fashion. Describe a cracked lens on his glasses, a bow fixed with stained tape, tufts of hair growing out of his nostrils, an odor of old laundry.”

—John D. MacDonald, The Writer (1974), reprinted in The Writer’s Handbook (1984)

How to recognize integrity:

“Integrity is not a conditional word. It doesn’t blow in the wind or change with the weather. It is your inner image of yourself, and if you look in there and see a man who won’t cheat, then you know he never will. Integrity is not a search for the rewards of integrity. Maybe all you ever get for it is the largest kick in the ass the world can provide. It is not supposed to be a productive asset. Crime pays a lot better. I can bend my own rules way, way over, but there is a place where I finally stop bending them. I can recognize the feeling. I’ve been there a lot of times.”

—via Travis McGee, The Turquoise Lament (1973)

When asked what he would like for an epitaph:

“He hung around quite a while, entertained the folk, and was stopped quick and clean when the right time came.”

—Interview with Ed Gorman, preserved at MysteryFile.com, previously featured in The Big Book of Noir, edited by Ed Gorman, Lee Server, and Martin H. Greenberg, Carroll & Graf, 1998.

On a healthy aversion to -isms.

“I know just enough about myself to know I cannot settle for one of those simplifications which indignant people seize upon to make understandable a world too complex for their comprehension. Astrology, health food, flag waving, bible thumping, Zen, nudism, nihilism—all of these are grotesque simplifications which small dreary people adopt in the hope of thereby finding The Answer, because the very concept that maybe there is no answer, never has been, never will be, terrifies them.”

—via Travis McGee, A Deadly Shade of Gold (1965)

On relationships:

“Friendships, like marriages, are dependent on avoiding the unforgivable.”

—The Last One Left (1967)

On betraying James M. Cain:

“I got a call not long ago from the New York Times asking me to review the new Cain novel…My first reaction was, is he still alive? Must be in his 80s. I read the book and it’s a…well, it’s impossible. All about Swedish maids with vibrators. What was I gonna do? I was fair to the book, I thought. And then they sent me $150 for the review, which had honestly never occurred to me. Being paid for it, I felt in some way I’d betrayed the SOB. He was good. I owe a lot to him.”

—July 28, 1976, Interview with Roger Ebert

Travis McGee on maturity, humility, resignation, and wariness.

“Being an adult means accepting those situations where no action is possible.”

—The Green Ripper (1979)

“The most deadly commitment of all is to be committed only to one’s self. Some come to realize this after they are in the nursing home.”

—The Lonely Silver Rain (1985)

“Education is something which should be apart from the necessities of earning a living, not a tool therefor. It needs contemplation, fallow periods, the measured and guided study of the history of man’s reiteration of the most agonizing question of all: Why?”

—A Purple Place for Dying (1964)

“Every day, no matter how you fight it, you learn a little more about yourself, and all most of it does is teach humility.”

—One Fearful Yellow Eye (1966)

“I am wary of a lot of things, such as plastic credit cards, payroll deductions, insurance programs, retirement benefits, savings accounts, Green Stamps, time clocks, newspapers, mortgages, sermons, miracle fabrics, deodorants, check lists, time payments, political parties, lending libraries, television, actresses, junior chambers of commerce, pageants, progress, and manifest destiny. I am wary of the whole dreary deadening structured mess we have built into such a glittering top-heavy structure that there is nothing left to see but the glitter, and the brute routines of maintaining it.”

—A Deep Blue Good-by (1964)