Many of us are familiar with the men of the Manhattan Project: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Edward Teller, dozens of male scientists rolling up their shirtsleeves in the Nevada desert. You may not be aware that thousands of women also contributed to the project, both in developing the science that made it possible and in running the top secret facilities where the atomic bomb was made.

The Woman With Two Shadows follows Lillian, who travels to the secret city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee where her twin sister Eleanor works on the Manhattan Project as a calutron girl. In order to find her twin, Lillian must pretend to be her. While researching Oak Ridge and the time period, I learned a lot about the fascinating and varied roles women played in the Manhattan Project. Here are just a few of them.

A woman discovered the scientific process that made the atomic bomb possible.

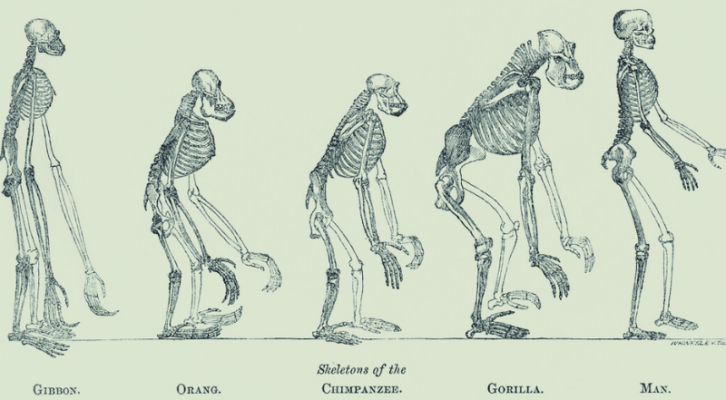

In 1938, Austrian physicist Lise Meitner and her nephew, physicist Otto Frisch, theorized that if one were to hit a uranium nucleus with a neutron, it might oscillate and elongate before eventually, under the right circumstances, splitting into two smaller nuclei. Meitner calculated the energy this process would release to be about 200 million electron volts. As Richard Rhodes describes in The Making of the Atomic Bomb: “Two hundred million electron volts is not a large amount of energy, but it is an extremely large amount of energy from one atom.” It was enough energy to make a grain of sand visibly jump, all from one tiny nucleus. Given that in each gram of uranium there are 2.5×1025 nuclei (that’s 25 followed by twenty zeros), the potential energy generated from this was enormous.

Meitner and Frisch named the process nuclear fission. It would become the basis of the atomic bomb developed in the Manhattan Project.

“Calutron girls” helped generate fissionable uranium at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Building an atomic bomb would require a large amount of fissile material. But scientists developing the weapon had a problem: the most common isotope of uranium is not fissionable, or not able to sustain the chain reaction needed for nuclear fission.

The Y-12 factory at Oak Ridge, Tennessee was built to solve this problem. There, the more common uranium-238 was separated into fissionable uranium-235 using a device called a calutron. This equipment needed constant monitoring, and since time was of the essence, that meant 24/7 shifts of calutron cubicle operators.

With many men off fighting overseas, the company in charge of the Y-12 facility recruited thousands of young women, many fresh out of high school from nearby cities in Tennessee, to monitor the cubicles in eight-hour shifts. In her book The Girls of Atomic City, Denise Kiernan describes how the women “usually minded at least two panels, each covered in knobs, dials, gauges, and meters.” These women had no idea what the various needles and dials they were monitoring were for, and as Kiernan puts it, “Smart girls didn’t bother asking.” In Oak Ridge, asking questions was suspicious, and being suspicious meant losing your job.

Women worked in many roles to keep the city of Oak Ridge running.

Not all of the women who lived and worked on the Manhattan Project sites worked directly on making the atomic bomb. As the Manhattan Project grew larger, more people had to relocate to the secret towns of Los Alamos in New Mexico and Oak Ridge in Tennessee. At its peak in the summer of 1945, 75,000 residents lived at Oak Ridge. These people needed to be fed, housed, entertained, and kept healthy. They needed to be cleaned up after, have their trash picked up, have their laundry done. Buses needed to be run so people could commute both around Oak Ridge itself and into the facility from nearby cities. Many of the individuals who relocated brought their families, so children needed to be educated.

To meet these needs, Oak Ridge had many amenities of a normal city: a hospital clinic building, a movie theater, a cafeteria, shops, and more. Women staffed the grocery stores, worked as nurses or janitors, and did administrative tasks like transcription or typing memos. Women also took on a lot of responsibility for bringing a sense of community and of normal life to the extraordinary living circumstances. Oak Ridge, for example, had its own Girl Scout Troop. According to Charles W. Johnson and Charles O. Jackson in their book City Behind A Fence, the Girl Scouts were such a powerful vision of normality in the town that the Army granted them the unheard-of privilege of selling calendars in the townsite without a formal contract.

A woman edited the Oak Ridge Journal.

Starting in 1943, Oak Ridge even had its own weekly newspaper: the Oak Ridge Journal. The Journal was edited by Frances S. Gates and several women also worked on the newspaper staff as columnists and reporters. By the summer of 1945, according to Jackson and Johnson, “circulation was approximately 26,000 copies per issue.”

As one may imagine, a newspaper in a town that was supposed to be a complete secret had a number of unique rules. The Journal was not allowed to print the names of project employees, leading the Journal to write in 1943 that it was “the only newspaper in the country without any news.” The Journal was able to advertise social events around the town as well as safety features and opinion pieces about living in Oak Ridge. The Army was quick to shut down stories that it felt could compromise security, but the Journal editorial staff maintained that with only a few exceptions, “we take orders from no one.”

***