When we decided at CrimeReads that our next roundtable would be with women who write espionage fiction, I really did not know what to focus on. How does espionage work in a Trump or post-Trump world? As this roundtable was back in the dark ages between the election and inauguration, I knew we’d have to address the orange man in the room but not how to put it into an espionage context.

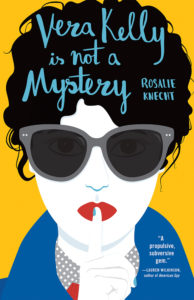

Fortunately, our excellent panel had many ideas about the political climate and the hallmarks of espionage: double-dealing, lying, manipulating, cheating, money, reputation. Once we got into our discussion it seemed inevitable that a regime like the one recently past would be chock full of these issues. Thanks to Lara Prescott (The Secrets We Kept), Lauren Wilkinson (American Spy), Rosalie Knecht (Vera Kelly Is Not a Mystery), and Tracy O’Neill (Quotients) for their keen insights.

___________________________________

“What’s the use of intelligence?

Or what counts as intelligence in a world that is so full of misinformation?”

___________________________________

Lisa: Well, let’s start with the Big Question. How do you write espionage during a global pandemic? And what happens next? I’ve found it’s good to ask the meaty questions up front because it sparks everyone’s thinking.

Rosalie: My book is set midcentury so it’s been a way to detach from the present and honestly, that has helped me a lot during this time.

Lisa: I think a lot of writers are using history as a distancing tool, which also has interesting implications. I see history being rewritten now, in all kinds of arenas. Why not in crime fiction?

Lauren: I think the thing that has more bearing than the pandemic on espionage as a genre, at least for me, is politics.

Lisa: Whose politics?

Lauren: How do you spy for a country with a government that’s so asleep at the switch that they’ve been indirectly responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans?

Where do you find your loyalty? How can it exist in an unconsidered state?

Tracy: Yes, the ethics of spying is really interesting right now—as well as the way in which intelligence on COVID was ignored. So another question is what’s the use of intelligence?

Lisa: Or what counts as intelligence in a world that is so full of misinformation.

Lauren: If you’re Kelly Loeffler you use it for the purposes of insider trading

Tracy: The president received intel briefings on the danger of COVID in January is what I’m referring to.

Rosalie: For me, after the George Floyd protests this summer, it felt hard to write even a very casual scene with police in it, which of course happens in noir all the time.

Lisa: Yes, I just did a roundtable with crime writers in California and police was the first thing they wanted to talk about. I’m very curious as to how people who write procedurals are going to handle this.

Rosalie: Yes, there’s a very easy Law & Order type cop scene that we could all write in our sleep that’s fun and familiar and it just brought it home intensely that maybe writing scenes like that is harmful.

Lisa: That’s why we are going to see a lot of paradigms shifting. Because things that used to feel normal are under scrutiny, and they should be.

Tracy: Rosalie, in your last book there’s a police raid on a gay bar. I think that is an excellent example of a writer using distance thoughtfully in crime. It is clear there that the police are doing harm. They aren’t the empathic center.

Lara: Trust in intelligence is at an all-time low. I mean, Pompeo, joking or not, was talking about smoothly ushering in Trump’s second term. That mistrust is definitely something to dig into as a writer.

Lisa: So no one trusts the police, and no one trusts the government…

___________________________________

Conspiracy, Ideology, and “Tom Clancy stuff”

___________________________________

Lara: I’m more interested in exploring the vastly different ways people arrive to that same conclusion.

I don’t believe our systems are set up to benefit all people. Others—fall into conspiracy. We both distrust, but for different reasons.

Lisa: That’s actually a fairly subtle difference. We end up at the same place—skeptical or worse.

The people who have been getting shafted all along get accused of believing in conspiracy theories, when actually they were right. The deck was stacked, etc.

And then, as you said, there are people for whom conspiracy is the only way to make sense of the world.

Rosalie: I think there may actually be fairly broad agreement in the U.S. right now that government doesn’t really serve the interests of the people, but the explanations given are radically different by political alignment.

I think it’s interesting that espionage as a genre was so huge in the ’50s and ’60s. Some of that is postwar cheerleading for the intel apparatus, I think, but just in general, did people trust the CIA in those days? I’m not sure they did. Or did the classic spy novel start fading out as the late sixties started?

I think probably in the 50s there was a sense that these were the people who had won the war. But after that?

Lisa: That’s a thorny question, isn’t it? There is always a doubt at the heart of espionage as to what people’s intentions are. All that lying for a living.

Rosalie: The classic double agent, or corrupt boss!

Lisa: But I do think culturally there was a lot less talking back to institutions than there is now.

And when we start questioning the apparatus, the next place to go is to question who is running it and how.

Lara: To me, there seems to be a tremendous rise in mistrust in institutions (and conspiracy) in the Post-Soviet era on both sides.

Rise of technology, Putin, Trump. It is mainstream.

Lisa: Agreed, Lara. That’s where Fox News gets its numbers.

Tracy: Much commercial espionage literature today—I’m talking about Tom Clancy kind of stuff—still cheerleads rather uncritically for US intel.

Lisa: But it’s also in the NYT bestseller list

And most of that espionage is written by men. And read by men.

Tracy: But that’s one thing that I really appreciate about Lauren’s book American Spy. It asks the spy narrative to engage with ideological investments.

Lauren: Thank you!

Lisa: Isn’t the spy novel always rooted in ideology at some level?

Tracy: Yes, but some writers don’t wrestle critically with ideology. Lauren does, and her character must weigh competing values. In other words, the difference is whether the text operates as an ideological barometer or a conversation with ideology.

Lauren: I think Marie is sort of like Vera (Kelly), in the sense that they both have to grapple with personal identity and self-perception to do the work they’ve been asked to do.

Rosalie: Yes! Asking the question of what it means for an individual and a personality to lie so much and to occupy that position socially

Lauren: So I don’t think it’s built into either character to just be blindly patriotic, not when every other insight comes with some struggle attached.

___________________________________

Why Spy?

___________________________________

Lara: There’s ideology and there’s the the individual. I like to think of the CIA’s recruiting mnemonic MICE (Money, Ideology, Compromise, and Ego). Ideology is there, but it goes beyond that.

Rosalie: I remember when I was writing the first Vera book and I was trying to figure out why anybody would agree to do this kind of work and what kind of ideology it would require and my boyfriend at the time said “people do it for money”—“it can just be that it pays well.”

Lara: Yep! Money, revenge, ego. Most people don’t switch sides because they had a change in politics. It is deeper. Tied to identity or circumstance.

Rosalie: I like how The Americans handles this question. There’s the full range. Elizabeth is a real ideologue, Philip isn’t sure anymore, so many people are just manipulated in a moment of vulnerability or weakness.

Lisa: I think that’s right, Lara. I’m thinking about the Neocons and a lot of their angst had to do with being Jewish. It was identity.

That’s true of a lot of crime fiction, Rosalie. Ultimately people are exploited either by institutions or by other people, people they trusted.

Rosalie: I think shame is a huge driver.

Lisa: How so? And how do you think shame ties into ideology?

Rosalie: Well, thinking of The Americans again, many informants are flipped because they’ve done something they’re ashamed of and they would do anything rather than have it be revealed. It’s not enough to drive the primary actors, who are or were at one time ideologically committed, but the ordinary people they run into are always being manipulated by shame about infidelity, money problems, their sexuality, etc etc.

Lisa: And that’s consistent with American thinking in the 1950s, that if people had a secret (eg they are gay) than they could be exposed, and manipulated.

Rosalie: This was the overt reason the intel services wouldn’t hire gay people for a long time. The idea was that it was too easy to compromise you because gayness was shameful and you wouldn’t want it revealed.

Lara: Thousands of people were fired from government jobs for that very reason … for decades. Many from the State department or CIA.

___________________________________

Shame in the Trump Era

___________________________________

Lisa: What else are people ashamed of? Or so ashamed of they would betray fill in the blank—their country, their family, their identity?

Really, how can we talk about shame in the Trump era? He’s kind of made it a moot point.

Rosalie: I think the classic James Bond figure is interesting this way—he’s completely devoid of shame, in the sense that he has no emotional vulnerability at all

Lara: Affairs, money, reputation. For Trump, the main shame would be to be forgotten.

Lisa: Narcissists hate it when you don’t pay attention to them.

Rosalie: Trump has this interesting flatness as a character. He’s all on the surface, completely available. Like Andy Warhol said, he’s just what he appears to be.

Lisa: But I think the operative word is character. It’s not who he is as a person, it’s the role he’s carved out for himself.

Lara: I feel like if he was a character of mine, my editor would be like—he needs more nuance! Our current events are almost stranger than fiction.

Lisa: Anyone want to add to that?

Rosalie: Just that a lot of the last four years has felt impossible to satirize. A real artistic problem for satirists.

Lara: Agreed.

Lauren: Definitely.

Lisa: One of my best friends is the showrunner for John Oliver. We were talking recently and he said there’s too much news. Comedy couldn’t keep up.

Tracy: And possibly for writers of spy fiction, the problem with writing this particular era will be that there is little sense of tension in the reveal.

Lisa: I hang around with other nonfiction writers and we all feel like no one would believe this if you wrote it as narrative nonfiction or history. And if you guys also can’t handle it, then where are we in terms of trying to represent and make sense of the state of the world?

Rosalie: When I was a kid I remember a movie trope where the good guys would, at the end, after finding proof of government corruption or whatever, get the story to a newspaper or TV reporter and the assumption was, ok, this movie is over now. Because this shocking information will be published, and the people won’t stand for this! Problem solved.

Lisa: That is the Watergate model.

___________________________________

“It’s time to get weird”

___________________________________

Lauren: When the symptoms are too outlandish to be believed, I think maybe that means just writing about the disease in other ways.

Tracy: Yes, when normative modes don’t work, it’s time to get weird.

Lisa. That sounds promising, Tracy

Tracy: I mean, I think about Borges’s plays on detective narratives, and they’re astonishing still.

Lara: Hence the rise one sees of surrealism in post-war / at-war countries. It is often the only way to make sense of a world that doesn’t make sense. I think we are going to see more of that in art in coming years.

Lisa: That’s an excellent point, Lara. It also is historically true that times like these—confusing, dangerous, unpredictable—have lead to innovation and a better system. But I think it’s too soon to tell.

Any final thoughts?

Lauren: Yes. I think it’s smart to get weird. And I think that right now feels like Watergate but it also feels like 1968 in a lot of ways—a president who is trying to run on a “law and order” response to social upheaval, for one thing. All of the news today is about the push to disenfranchise black voters. Right now it’s in Detroit, but that’s a pretty consistent theme in this country. There are problems built into the country’s DNA that keep creating the same kinds of scenarios, but with the details changed. So you can write about the problems without writing about one particular orange moron who happens to be a consequence of them.

Rosalie: Exactly, Trump is a unique personality but all of the structures that allowed this to happen are old, old, old.

Lauren: Yes, exactly. Some people just write the structures and people think they’re prescient but it’s just pattern recognition.

Lara: Final thought: I hope you all keep writing and keep safe. We need your future books. I need your future books!

Rosalie: Yes, cosigned!

Tracy: One way to do this, I think, is to subvert precisely the narrative paradigm in which there is a single antagonist. We need to learn to tell stories about structures and systems, stories which are much more diffuse.

Lisa: That seems right to me, Tracy. I hope that whatever the other side of this looks like there is a sense that some real, deep-rooted social wrongs can start to be addressed if not corrected.

I think that’s a good note to end on. Thank you all for being here!