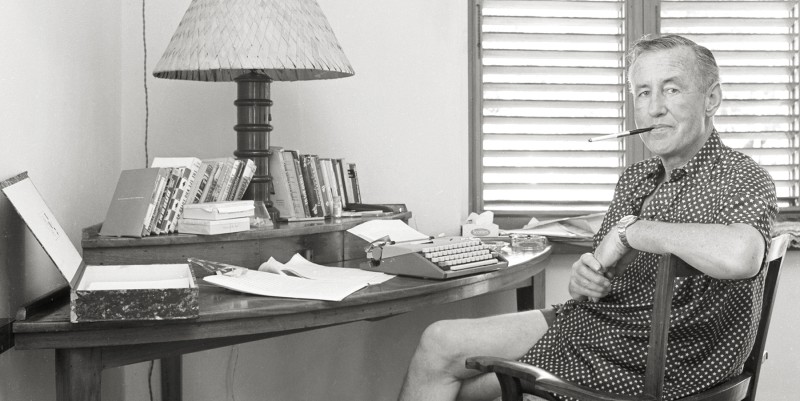

After five years of procrastination, Ian Fleming sat down at the typewriter.

He began to write not for the joy of creating, but as a way to avoid reality. He was forty-three years old and troubled by thoughts of the future. At the typewriter, he could escape reality and dream about the person he would rather be.

On the surface, Fleming’s life looked idyllic. It was 1952, and he was wintering in Goldeneye, a simple one-storey house near Oracabessa on the north shore of Jamaica. He had had this house built after the end of the Second World War, with the intention of using it as a winter writing retreat. It was quite an ugly, sparse building, to the eyes of those used to beauty and luxury, and it lacked basic amenities like cupboards, hot water and even glass in the windows. It did include a separate garage which served as staff quarters, however; although he saw it as a rough, rugged, masculine retreat, Fleming still wanted servants.

Outside Goldeneye, the views and the weather were as close to paradise as you will find on this earth. So too was the act of walking through the rough garden and taking the steps down to the beach, entering the warm clear water and snorkelling among the coral of the Caribbean. Fleming left London and came to stay at Goldeneye for three months every winter. His life, clearly, was markedly different to that of his fellow Englishmen who were born in the Dingle. It was not hard to see why it took him five years to start his novel.

Fleming was depressed and drinking heavily. He was also about to get married. His fiancée, Ann, was the love of his life and pregnant with his child, but this didn’t mean that he wanted to be married to her. He began writing, he later admitted, to take his mind off the ‘hideous spectre of matrimony’. A committed relationship requires a level of emotional maturity which he did not possess. Mutual friends suspected from the start that the marriage would be a disaster. As the playwright Noël Coward noted in his diary, ‘I have doubts about their happiness if [Ann] and Ian were to be married.’

When the pair first began their affair, Ann was married to an aristocrat and had the title Lady O’Neill. After Lord O’Neill was killed in action in the Second World War, she considered continuing her relationship with Ian, but decided against it. Instead she married Viscount Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail. In Ann’s opinion, Rothermere’s title and wealth made him a more attractive husband. The marriage was not a fulfilling one, however, so Ann and Ian resumed their affair. Their physical relationship was a BDSM one, in which Ian inflicted pain on Ann. As she wrote to him after a liaison in Dublin in 1947, ‘I loved cooking for you and sleeping beside you and being whipped by you and I don’t think I have ever loved like this before [. . .] I love being hurt by you and kissed afterwards.’ In a letter Ian wrote to Ann during the war, which was sold by Sothebys in 2009, he told her that ‘I love whipping you & squeezing you & pulling your black hair, and then we are happy together & stick pins into each other & like each other & don’t behave too grownup & don’t pretend much.’

Although Ann and Ian’s stormy relationship was an open secret in the social circles they moved in, Ann and Viscount Rothermere didn’t divorce until after she fell pregnant with Ian’s child. This left the pair finally free to marry. As Ian wrote in a letter to Ann’s brother ahead of their wedding, ‘We are of course totally unsuited . . . I’m a non-communicator, a symmetrist, of a bilious and melancholic temperament . . . Ann is a sanguine anarchist/ traditionalist. So china will fly and there will be rage and tears. But I think we will survive as there is no bitterness in either of us and we are both optimists – and I shall never hurt her except with a slipper.’

Most of Fleming’s biographers link his fear of marriage with his lack of healthy emotional relationships in his formative years. His grandfather was Robert Fleming, who developed the concept of investment trusts and who founded the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co. Robert Fleming has been called ‘one of the pioneers of investment capitalism’; he made his family extremely wealthy. Robert’s son and Ian’s father was Valentine, a Conservative Member of Parliament who was killed in action at the Battle of the Somme in the First World War. His obituary in The Times was written by his friend Winston Churchill.

Ian was only nine when Valentine died. He was brought up to see his father as the epitome of male virtue – brave, successful in worldly affairs, incredibly rich, and entirely absent. As paternal figures go, Valentine was impossible to live up to. Fleming and his siblings used to end their nightly prayers with the words, ‘and please, dear God, help me grow up to be more like Mokie’ – their nickname for their late father, a child’s variation on ‘smokey’, because of Valentine’s love of pipe smoking. The family nickname for Fleming’s mother Eve, curiously, was ‘M’.

Eve was less admired than her late husband. She was beautiful but could be domineering and was, according to her granddaughter, ‘a quite frightening woman’. She was aware that young Ian was sensitive, but she liked to humiliate him in public regardless. A cruel clause in her husband’s will meant that she would be cut off from his family’s wealth if she ever remarried, so Eve chose wealth over love and remained single for the rest of her life. When she later became pregnant by the painter Augustus John, she went away for the rest of the year and returned with a baby she claimed was adopted. Later, when Ian was in his early twenties, he became engaged to an Austrian girl he had fallen in love with, who Eve didn’t approve of. His mother made him an ultimatum: either Ian split from his fiancée or she would cut him off from the family money. Ian also chose wealth over love and ended his engagement. Had he made a different choice, like the brigadier’s daughter Jeanette, his life may have been very different.

Ian was sent away to a series of elite boarding schools. His first, Durnford, was described by Fleming’s friend and biographer Andrew Lycett as ‘a harsh and often cruel establishment [. . .] If it existed today, it would certainly be closed down.’ Durnford led to Eton, where his housemaster was bluntly described, in Tim Card’s official history of Eton, as a sadist. Interviewed for a 2006 documentary, his friend Tina Beal recalled how at Eton, Fleming ‘was scheduled to be beaten and he was going to run in a cross-country race, so he applied to be beaten early so that he would be in time to run in this race’. At Eton, it was the tradition that boys were beaten at noon. ‘They beat him so savagely that blood came through his trousers and he ran the race with blood coming through his pants,’ Beal continued. ‘He finished second!’ As Lycett described the incident, Fleming ran the steeplechase with ‘his shanks and running shorts stained with his own gore’.

To modern eyes, the delight and amusement with which Beal recounts this story is disturbing. Beating children was then accepted as normal. There was little awareness that such trauma could leave lifelong psychological scars. As his friend Robert Harling has argued, it was Fleming’s time in English boarding schools that forged his ‘imprisonment of emotions’. As Harling observed, ‘the English upper crust wants and needs affection as deeply as any other crust, but impulses towards this important emotional release are frequently stifled for them [. . .] the boys grow up, professing to hate what they so need.’

Faced with an imminent wedding and a pregnant fiancée, with all the responsibility, commitment and emotional understanding that this entailed, Fleming struggled with his innate desire to escape. It was this that finally pushed him into sitting down at his typewriter and starting his long-threatened novel. He would create a hero who was an avatar of himself, with the same tastes, background, opinions and prejudices, but with none of the troubles that weighed so heavily on him – an unashamedly unemotional masculine fantasy. Fleming could then set that avatar free to live the life he fantasised about, but could not have himself. He stole the name of the author of Birds of the West Indies, a book he had on his desk, and called the hero of this novel James Bond.

Fleming was growing into middle age at the time, and he had a long list of complaints about both himself and the direction that the world was going. In the real world these were things that he had no control over, and they made him feel weak and insignificant. In the world of the imagination, however, they were things that he could change, or simply deny, whichever he preferred. There was no end, he would discover, to the liberation found in fiction. The first of these complaints was his health, which had already started to deteriorate. Suffering from chest pains, Fleming had been advised to cut back on alcohol and cigarettes. The problem was that he didn’t want to. Like a spoiled child, Fleming clung to the idea that he should be able to live as unhealthily as he liked while still remaining virile and energetic. His James Bond avatar, then, would be younger, smoke as much as he wanted, and drink like a fish. Research published in the Christmas 2013 edition of the British Medical Journal reported that, across all of Fleming’s novels, Bond drinks an average of ninety-two units of alcohol a week, significantly more than the recommended fourteen. In Casino Royale, Fleming refers to Bond smoking his ‘seventieth cigarette of the day’. Even in fiction, this takes a toll. In the novel Thunderball, Bond’s blood pressure is revealed to be a frightening 160/90.

The issue of Fleming’s coming marriage was obviously another concern. Fleming wanted to sleep with glamorous, exciting women, and he wanted them to fall for him in the same way they used to when he was younger. Then he just wanted them to disappear afterwards, and not talk about marriage. Fleming had previously had a girlfriend who was killed during the war. This was a tragedy, but to Fleming it was also a neat solution. The idea that women would die after falling into bed with Bond entered the novels. It quickly became a recurring pattern in the secret agent’s relationships.

Then there was the issue of his war record. Fleming had been in Naval Intelligence and had held the mid-ranking title of commander. He was proud of this title and insisted that his Jamaican servants called him by it. The war had taken him twice around the world and there is no question that he had served his country with honour, but the reality of his service embarrassed him. He had been the personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence, a cushy desk job he had been handed through family contacts, and he had never seen action or been exposed to any danger. He was the man who sent other men into battle while he lived a secure and comfortable life a long way from the front. He was referred to as a ‘chocolate sailor’, a nickname that defined him as not a ‘real’ member of the navy. Bond, in contrast, would also be a commander in Naval Intelligence, but he would lead from the front, fighting the enemy face to face like Fleming’s father had. Bond would refer to himself as ‘strictly a chocolate sailor’ on board an American submarine in the novel Thunderball, but he did so in a charmingly self-deprecating way. There were no question marks about Bond’s bravery.

Another issue was Britain and its standing in the world. Fleming’s education and upbringing had taught him to unquestioningly believe in British exceptionalism – that Britain was automatically ‘better’ than other places, and that the British Empire had been a force for good. Like many, he saw the world as it had been during his childhood as right and proper, and any changes that occurred later as terrible mistakes. The thought that the British Empire was ending, unloved and unwanted, was too horrible to contemplate. He remained in denial for as long as he could. Like many of his class, he never really understood why Winston Churchill was defeated in the 1945 general election. Fleming was firmly against the post-war welfare state and the creation of the NHS which saved Ringo’s life.

In Fleming’s eyes, Jamaica was one of the last places on earth that preserved all that he admired about the Empire. Here a British gentleman could enjoy an exotic but civilised life, where the climate was agreeable and the servants weren’t too rebellious. It was a place where he could fool himself that the sun would never set on the British Empire. This image of Jamaica was delusional, of course. It was certainly not shared by the Jamaican people themselves. Ending ties with Britain dominated local politics and within a decade, Jamaica gained its independence.

A key moment in the end of the British Empire was the Suez Crisis of 1956. This was a moment of clarity for those who still saw Britain as a global power. As the Deputy Cabinet Secretary Burke Trend explained, Suez was ‘the psychological watershed, the moment when it became apparent that Britain was no longer capable of being a great imperial power’. In the aftermath of this ill-fated attack on Egypt, Prime Minister Anthony Eden fell ill. He decided that a holiday in Jamaica would help him recover, and he chose to recuperate at Fleming’s Goldeneye. His Conservative Party colleagues plotted against him in his absence, and he was removed from office three weeks after his return. Goldeneye, the house where James Bond was born, was the last refuge for those still in denial about Britain’s place in the world.

An unquestioning belief in Britain was vital to the character of Bond. It was the source of another thing that Fleming desired, which was an ethical and moral excuse to be above the law and to do whatever he wanted. Bond famously has a licence to kill, which raises the question of who has the right to grant someone permission to murder. The answer, as Fleming and Bond saw it, was the British crown. Bond’s enemies also killed and destroyed, of course, but they did so without the correct paperwork and authority. This made them bad. His licence to kill and the freedom it offered has proved to be a major part of James Bond’s appeal.

Last but certainly not least, Fleming gave Bond absolute mastery of the physical world. He was a skilled pilot, marksman, driver, gambler, skier, linguist, bomb disposal expert, diver, lover, or any other skill that the plot demanded. He knew exactly what food, drinks, clothes or cars were the best available. More importantly, he would always triumph. He could suffer, but whatever scheme or plot he attempted, no matter how implausible, would always succeed. This was aspirational fantasy at its most alluring. Wherever he went and whatever he did, the material world bowed in his presence, subservient to its master. The spiritual or immaterial world, on the other hand, was almost entirely ignored.

___________________________________

Excerpted from Love and Let Die: James Bond, The Beatles, and the British Psyche, by John Higgs. Copyright 2023. Published by Pegasus Books. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.