Rudyard Kipling brought sex to the movies.

The author of “Gunga Din,” “The Man Who Would Be King” and “The Jungle Book” didn’t intend to do it, but he certainly bears some responsibility for the morass of cinematic depravity in which we so happily wallow today. However inadvertent his contribution, he helped create the screen’s first seductress, a woman as “wicked as fresh red paint.”

Her career was brief and almost all of her films have been lost, but in her day, she was one of the world’s most popular stars.

It happened this way.

At 32, Kipling had published several volumes of stories and poems and was enjoying wide-ranging popular and critical success. After traveling around the world and living in America for several years, he had settled in England. The artist Philip Burne-Jones was his cousin and close childhood friend. Little Phil was the son of the eminent Victorian pre-Raphaelite painter, Sir Edward Burne-Jones.

In the London of 1897, the younger Burne-Jones was a well-to-do young man about town. A rising if somewhat dilettantish artist, he was struggling to get out of his father’s shadow. He would never measure up to Big Ed in that regard, but Phil was enough of a stud muffin to be seen with Mrs. Patrick Campbell on his arm, and that was really something. Mrs. Pat, as she was called, was one of the most famous stage actresses of her day. A favorite of George Bernard Shaw, the diva was notorious for her temperamental behavior and richly varied social life. (Mr. Campbell was not an issue.) Her rough equivalent might be a young Liz Taylor, respected for her acting abilities and gossiped about at delicious length.

Little Phil fell hard for Mrs. Pat and plied her with jewels, flowers, carriages. Alas, those weren’t enough. Some suspected that Mrs. Pat had merely used the lad to get close to Big Ed, but whatever the reason, after toying with his affections for a time, she tossed him aside for one of her co-stars. Phil did not take it well.

He uncorked his anger, resentment, and bruised ego and poured them onto canvas in a painting he called “The Vampire.”

It depicts a handsome young man stretched out supine on a chaise in his bedroom. His clothes are open, revealing his chest. If contemporary accounts are to be believed, the guy in the picture looks like Phil but taller, slimmer and with more hair. Looming above, a beautiful long-haired woman gazes down on him. With a cool cruel expression on her face, she is, unmistakably, Mrs. Campbell.

When the painting made its debut at the New Gallery, it became an immediate scandalous sensation. Everyone knew who the figures were and what was rumored to have happened between them. To fan the flames, Little Phil inveigled his cousin Rudyard to write a poem to accompany the painting. Kipling agreed and cranked out his own “The Vampire” in six verses. It begins:

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care)

But the fool he called her his lady fair—

(Even as you and I!)

Straightaway, Little Phil commissioned a limited run of signed first editions of his cousin’s work. (They sold. The painting did not.)

Both poem and picture were both extremely popular in England and later in America. Beyond the immediate reference to such a famous woman, the painting touched something in the audience. It was an obvious variation on the sexual themes and undercurrents of Bram Stoker’s novel “Dracula” which had been published that same year. Both are built around seductive figures creeping into bedrooms late at night.

The scandal over the painting died away but Kipling’s poem remained popular and in 1909, Porter Emerson Browne expanded the basic idea into a stage play and quickie novel with the title taken from the first line, “A Fool There Was.” The plot is a fairly standard Victorian melodrama about drunkenness, infidelity and the destruction of a happy family. Browne added the element of the predatory seductress from Burne-Jones and Kipling. Though the New York Times dismissed the piece as “claptrap,” audiences flocked to see it and the play was a major hit.

Four years later, independent producer and theater chain owner William Fox was trying to step up from simple one-reel films to more complex (and profitable) feature-length stories. (His studio would eventually become the Fox in 20th Century Fox.) His first major acquisition was Browne’s play.

He reasoned correctly that it would be a good vehicle for a new kind of star, a darker antidote to Mary Pickford’s “America’s Sweetheart,” and he got some good advice from the play’s producer, Richard Hilliard. He told Fox to lock his leading lady into a long term contract before he shot the first frame of film. Over the years, Hilliard said, he’d replaced his actress six times because the role was so good that it made each young woman extremely popular and “difficult.”

Theodosia Goodman was exactly the kind of woman William Fox was looking for. She’d moved to New York from Cincinnati in 1905 with dreams of becoming a stage actress. The movie business was in its infancy then and she wanted nothing to do with it. But after several years of minimal success on Broadway and in Yiddish theater, she took a more accommodating view of the new art form and looked for any work she could find in the studios across the river in Ft. Lee, New Jersey. That’s where Fox studio director Frank Powell spotted her in 1914.

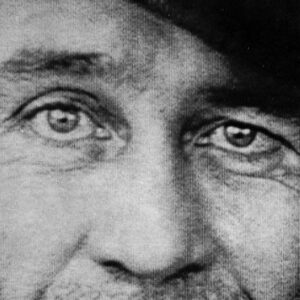

By then, she was staring grimly at 30 and knew that she was overweight. The waif look was in that year, and even at her most svelte, Theodosia was a large woman. But Powell saw something. Maybe it was the long lush dark hair or her expressive eyes. Whatever it was, Powell hired her but made sure that she stayed in the background on his film, “The Stain.” He didn’t want anyone else to spot her. Not then.

William Fox then signed her to a five-year contract at $100 a week, and announced with great fanfare that he was searching for an unknown actress to star in his upcoming production of “A Fool There Was.”

Filming began in the fall of 1914 on location in St. Augustine, Florida, and ended in New York. It was ready for release in January, 1915. Reviews were generally positive, particularly for leading lady Theda Bara.

Yes, Fox and his imaginative p.r. flacks Johnny Goldfrap and Al Selig decided that Theodosia Goodman from Cincinnati simply wasn’t sufficiently alluring and mysterious for the movies’ first bad girl, and so they created Theda Bara.

This exotic creature, born in the shadow of the Sphinx, was the daughter of a French artist and his Arabian mistress. The name actually came from a diminutive of Theodosia and a variation on a family name Barranger. It was only later that someone realized the name was also an anagram for “Death Arab” and added that little detail to the increasingly fanciful Theda mythos. And Goldfrap, Selig and company were tireless in their elaboration of that mythos with press conferences featuring incense, dim atmospheric lighting and crystal balls, all promoting “the Wickedest Woman in the World.” That’s what Terry Ramsaye was referring to with the “red paint” metaphor for Theda in his history of silent movies, “A Million and One Nights.”

Just a few days before the premiere of “A Fool There Was,” they held their famous introductory press conference with a few reporters to “introduce” their new star. It took place in a heavily curtained Chicago hotel room, thick with incense. Theodosia was decked out in furs and veils and played Theda to the hilt. After it was over, Goldfrap and Selig told one reporter, a young unknown Louella Parsons, to hang around. She was on hand to see Theodosia rip off the costume, throw open the drapes and gasp “Gimme air,” just as the boys had planned.

At the very moment they were creating Theda the Sex Goddess, they were revealing their own charade. It worked. Doubtless a few people actually bought the Theda malarkey but most, if they paid any attention at all, simply enjoyed the silliness of the whole business.

And what of the film itself?

By the time it was released, Kipling had won the Nobel Prize for Literature and so his poem was often recited aloud by an actor before a screening, thereby adding a degree of respectability to an unashamed exploitative potboiler. It tells the story of a sexy young woman who seduces and casts aside a series of lovers. The Vampire, as she is called, sets her eye on upright John Schuyler (Edward Jose). The happy husband and father of an angelic little girl has just been given a special European assignment by the President, and is about to leave by himself. The Vampire books passage on his ship, the Gigantic, and straightaway goads her current lover into suicide after she famously says to him, “Kiss me, my fool!” (It became an instant catchphrase and punch line.)

Moments later, she meets Schuyler and nails him with a smoky glance. Cut to her boudoir in Italy where a dissipated Schuyler opens a letter from his wife asking why he hasn’t written. His face is lined, his complexion is sallow, his hair is white, his hands tremble. The Vamp has him under her spell. What is her power?

On screen, it’s mostly the eyes. They’re surrounded by mascara that appears to have been applied with a putty knife. The rest of her face is pale zombie white. The primitive lighting and makeup techniques of the day demanded such harsh overstatement. With that extreme appearance, Ms. Goodman was able to level an intense stare at the camera and her co-stars. She also wore a series of fairly revealing outfits. In one scene, she’s in constant danger of falling out of her negligee as she packs her trunk. Beyond that, she’s an energetic, animated full-bodied woman who acts on her sexual desires.

Such a character had not been seen before and audiences were stunned. Women everywhere wanted to share her power. Humorist S.J. Perleman spoke for most men when he summed up his reaction to film. “For a month afterward, I gave myself up to fantasies in which I lay with my head pillowed in the seductress’ lap.”

Despite the imprimatur of Nobel, the film was roundly condemned by responsible civic and religious organizations, and it was cut severely by many state censors. Everybody else loved it, and the film became a certified boffo box office smash. The public relations ploy worked better than anyone could have predicted. Theda Bara was immediately identified as “the vamp.” It had been her nickname on the movie set, and the use of the word to describe a seductive woman entered the language.

Fox immediately set to work on more vampish vehicles for its new star, and the studio cranked them out as fast as it could. Theda Bara starred in no less than 60 features over the next four years. That’s not a misprint—60 pictures in four years. True, many of them were little more than an hour long, but she worked at a crushing pace, and some of the productions were lavish. Judging by the photographs and publicity stills that survive, her 1917 “Cleopatra” was a visual marvel with huge sets and outré costumes that beggar description. We’re unlikely ever to know because all known prints were burned, along with most of her films, in a fire at the Fox studio.

(Lon Chaney’s “London After Midnight” and “Cleopatra” are the two holy grails of lost films.)

Theda made a few pictures in which she played the “good girl,” but those weren’t what her public wanted to see and they fared poorly. The vamp wasn’t playing so well, either. By 1919, Theda had grown tired of the character and retired from filmmaking.

She decided to take another run at the stage and in 1920 she opened on Broadway in “The Blue Flame.” If the reviews are to be believed, it was a terrible play and she was terrible in it. But once again, audiences disagreed and the production made Theda a wealthy woman. When it was finished, she embarked on a vaudeville tour and that made her even wealthier.

A year later, she married one of her favorite directors, Englishman Charles Brabin. She retired then, though he continued to work regularly, and they divided their time between Hollywood and New York.

In contrast to her public relations portrayal of the Wickedest Woman in the World, the real Theodosia/Theda was a quiet, bookish woman with a smart sense of humor. Her private life was notably restrained—no problems with drugs or alcohol, no outlandish spending. At the height of her fame, she lived in a relatively modest Upper West Side apartment and made sure that her family was financially secure. As her biographer Eve Golden notes, that lack of scandal or controversy in her private life is at least part of the reason that Theda Bara has been forgotten today. Many moviegoers may recognize the vamp caricature with its dark eyes, but they may not associate it with Theda Bara.

She talked of returning to the movies later in life, but few stars were able to make the transition from silent to sound and her heart wasn’t in it. But she did maintain her contacts in the entertainment business and that led to a fitting postscript.

In the early 1930s, Mrs. Patrick Campbell was attempting to revive her fading stage career by offering her services to the American movies. Every bit as demanding and contrary as she had ever been, she had a tough time of it. Her biggest role was as the pawn shop owner Peter Lorre kills in “Crime and Punishment.” But when Theda learned that Mrs. Pat was in the country, she offered her a place to stay. She also publicly pooh-poohed all the stories that were being told about how “difficult” Mrs. Pat was and went out of her way to praise the older woman’s abilities.

No one knows if they ever talked about “The Vampire” who connected their careers but it’s hard to believe they didn’t.

***