Lawman.

The word calls a specific image to mind. Rugged features, weathered skin, bushy moustache. He’s got a hat on his head, a gun at his waist, and a tin badge on his chest, and he’s a one-man embodiment of the American Old West.

In an era populated with colorful characters—the gunfighter and the gambler, the outlaw and the prospector—no one loomed larger than the lawman. Some of the most notorious figures of the day, including Wild Bill Hickock, Wyatt Earp, and Bat Masterson, wore a badge. Not that this stopped them from pursuing other endeavors, not all of them strictly legal. Lawmen of the Old West were gunslingers, gamblers, prospectors, prize fighters, buffalo hunters, and even outlaws. Small wonder they so captured the imagination of the American public—and of her 26th President, Theodore Roosevelt.

TR was himself a lawman, having served as deputy sheriff of Billings County, Dakota Territory in 1885-1886, and as police commissioner of New York City ten years later. He had a deep and abiding respect for the law and those who upheld it, and maintained lifelong friendships with a number of famous frontier lawmen. He even appointed several of them to positions in federal law enforcement—prompting the press of the era to refer to them collectively as “the White House Gunfighters.”

I first became acquainted with this fascinating facet of Rooseveltian history while doing research for The Silver Shooter, a Wild West mystery featuring Theodore Roosevelt as a character. One of my favorite television shows of all time was HBO’s Deadwood, so imagine my delight upon discovering that one of TR’s closest confederates from his Dakota days was Seth Bullock, onetime Sheriff of Deadwood.

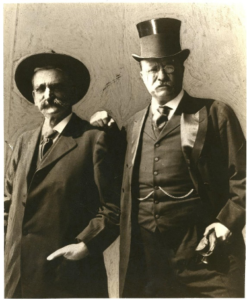

Seth Bullock (left) and Theodore Roosevelt

Seth Bullock (left) and Theodore Roosevelt

According to TR’s autobiography, their first meeting was less than cordial, with Bullock inquiring after a horse thief Roosevelt had arrested “with a little of the air of one sportsman when another has shot a quail that either might have claimed—‘My bird, I believe?’” TR seems to have smoothed it over, however, and Bullock became one of his “staunchest, most valued” friends. The legendary lawman even presided over a posse of 50 Dakota cowpunchers as part of TR’s inaugural parade in 1905, an event described with breathless delight by the newspapers of the day.

Interestingly, Bullock wasn’t officially considered one of the White House Gunfighters, perhaps because his reputation was too squeaky-clean. The same could not be said of ‘official’ members Pat Garrett (famous for gunning down Billy the Kid) or Ben Daniels, a former assistant marshal of Dodge City whose stint as a lawman ended when he was tried and acquitted for a murder he almost certainly committed. When TR appointed these men to federal positions—Garrett as Collector of Customs in El Paso (1901) and Daniels as US Marshal of Arizona Territory (1902), the outcry was swift and furious. In the case of Daniels, he was forced to resign barely a month after accepting the post (though he was reappointed three years later).

The most famous of Roosevelt’s White House Gunfighters was William Barclay “Bat” Masterson, former Sheriff of Dodge City and acquaintance of many of the era’s most famous figures, including Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and Buffalo Bill Cody.

Bat Masterson in 1879

Bat Masterson in 1879

Masterson was working as a journalist in New York City when he was introduced to Roosevelt, who appointed him Deputy US Marshal for the southern district of New York in 1905. Perhaps scarred by his previous missteps, TR seems to have been a little nervous about the appointment, writing to Masterson:

“You must be careful not to gamble or do anything while you are a public officer which might afford opportunity to your enemies and my critics to say that your appointment was improper.”

Masterson managed to avoid controversy until 1909, when Roosevelt’s successor, President Taft, decided he’d had enough, and the last of the White House Gunfighters rode off into the sunset (or at least, into the office of the New York Morning Telegraph, where he covered boxing for his remaining years).

If TR’s Wild West lawmen proved a little too wild for the White House, it could hardly have come as a surprise – least of all to Roosevelt himself. After all, he knew better than most the sorts of characters he was dealing with. Take the sheriff under whom he’d served as a frontier lawman himself in Medora, Dakota Territory.

Hell Roaring Bill Jones

Hell Roaring Bill Jones

“Hell Roaring” Bill Jones, Sheriff of Billings County, didn’t leave much of a footprint on the historical record, but he certainly made an impression on the future president. As he appears in TR’s autobiography, Jones is an erratic figure, whose “unconventional” approach to law enforcement seems largely to have consisted of beatings and the threat of beatings. Jones came to Medora via Bismarck, where he’d served as a police officer until he pistol-whipped the mayor, at which point he was politely asked to resign. A gunfighter and “thorough frontiersman,” Jones was nevertheless “a little wild” when drunk, at least according to TR. Sadly, that condition became the rule rather than the exception, which may have contributed to his eventual demise in a blizzard in 1905.

Even knowing these rough-and-ready fellows as he did, Roosevelt couldn’t resist bringing them into the fold – just as I couldn’t resist bringing some of them into The Silver Shooter. There’s just something about these larger-than-life lawmen that grips the imagination. I can’t promise my portrayal of Hell Roaring Bill Jones or Seth Bullock is historically accurate, but I can promise bushy moustaches, black felt hats, gun belts, and tin badges. Because when you throw those delightful ingredients into the mix, things are sure to get “a little wild.”

***